You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Karmic Consciousness and Zen Awakening

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk explores the concept of karmic consciousness and how past actions shape our perceptions, especially the illusion of externality, as described in Zen teachings. It highlights Bodhidharma's emphasis on simplicity and the story of his interaction with Emperor Wu, illustrating transcending dualistic views. The discussion also touches on recognizing and overcoming the habitual projection of self and external separateness, advocating for a practice rooted in compassion and self-awareness.

- Avatamsaka Sutra: Discussed in the context of ignorance being the immutable knowledge of all Buddhas, indicating that sentient beings and Buddhahood are intrinsically linked.

- Heart Sutra: Briefly mentioned in relation to Avalokiteshvara seeing the selflessness of phenomena, focusing on the realization of no intrinsic self.

- Dharanas and Mantras: Suggested as tools for calming the mind and breaking free from the compulsion of language, aiding deeper understanding of selflessness.

These texts and practices are key to understanding the nuances of non-duality and enlightenment as depicted in Zen philosophy.

AI Suggested Title: Karmic Consciousness and Zen Awakening

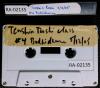

Speaker: Tenshin Roshi

Possible Title: #4 Bodhidharma

Additional text: Tenshin Roshi class

@AI-Vision_v003

You know, sometimes we say traditionally blah, blah, blah. So I would just say that traditionally that chant is done three times. But at Zen Center now we do it sometimes two. We do Japanese sometimes and then English. But in other parts of the Buddhist world it's often done three times. And I think usually it used to be done... mostly three times. Chanted that we would, we vow to taste the truth of the Tathagata's words. And are there any Tathagata's words that anybody knows about? There was a circle here around the stone. Most of the morning, a rainbow circle.

[01:08]

A friend of mine was trying to quote Darren Vick and to quote it for that. Shakyamuni Buddha apparently was a rather talkative Buddha. There's like many, many what are called sutras or scriptures recording his speech. Did you know that? Many, many talks he gave. Some are quite short and some are fairly long. But Bodhidharma was apparent, you know, we hear anyway that he was not so talkative.

[02:18]

A somewhat different type of a person or a different form of manifestation from the Buddha. For example, there's a story that when Bodhidharma came to China, he had an interview with the emperor of China, the emperor of, the emperor, emperor Liu, no, emperor Wu of Liang, the Liang dynasty. So he had an interview with Emperor Wu. And in that interview, the emperor had quite a bit to say. The emperor actually had done quite a bit of study before meeting Bodhidharma. And then when he met Bodhidharma, not only did he study, but he built quite a few monasteries

[03:22]

and supported the monasteries after he built them. And then I think he said something like to Bodhidharma, what's the merit, how much merit is there in all this that I've done? And Bodhidharma said, no merit. And then the emperor said something like, what's the highest meaning of the holy truths? And Bodhidharma said, vast emptiness, no holy. And the emperor said, who is this that's facing me? And Bodhidharma said, don't know. Or don't know. And then Bodhidharma left. He didn't say that much to the emperor. Just about three sentences. That was it. And then he left. And after he left, the... the imperial teacher said to the emperor, did you by any chance know who that was?

[04:26]

And the emperor said, no, I don't know. And he doesn't know either. And the imperial teacher said, that was Avalokiteshvara, bodhisattva of great compassion. And the emperor said, oh, let's have him come back then. And the teacher said, I don't think you can get him to come back. I think you had your interview with Avalokiteshvara and that's, you know, to live with that. And then Bodhidharma went up into the northern part of China and went to a place called the Little Forest and sat cross-legged facing the wall for nine years. And then this excellent student came to him somebody who had, I think, who had already studied quite a bit of the Buddha's teaching. And finally Bodhidharma accepted him as a student and he didn't say much to him either.

[05:37]

He just said, well, he said more than these four lines, but these four lines were the basic teaching he gave him. And they worked on his teaching for a long time. But he didn't give them exactly more teaching. He just assisted him in his attempts to understand how to practice outwardly ceasing all involvements or ceasing all involvements with externals. He basically just worked with him on that. And someone said to me that when I put those four lines on there that they thought that I would put the four lines on and then I would go on to give more teachings here during this week. Because that's not very much. But I kind of want to be a disciple of Bodhidharma. Now some of you know I've given some extensive teachings in the past.

[06:39]

But this week I'm kind of in the bodhidharma mood. And so I'm not giving you much this week. Just four lines. And now, if you want to, you can practice those four lines. You can outwardly cease all involvements and enter the Buddha way. And if you have any problems with that, I'd be happy to be of any assistance I can. You might even ask me to give more teachings other than this one, because you don't like this one. And I welcome you to say that, although I might not give you any more teachings than that, because if it was good enough for Bodhidharma, it should be good enough for me.

[07:42]

but maybe not. Maybe it's not good enough. And also, if you don't have any, if you don't want to practice it, or if you don't have any comments on it or questions on it, that's okay. Ladies first. Um... It's just you know at least in part that we can only work with your own chronic qualities and conditions. And that everything external is going to be either colored or painted or distorted or by your chronic conditions, process and conditions, and it's totally purified. Could you hear what she said?

[08:48]

I'm not surprised. She didn't yell that, did she? No. Let's see if I can rephrase something like what she said, because I have a microphone that is connected to an amplifier. And she said something like, does this mean you only have your own karmic conditions and that if you work with something outside that, that that will be kind of like defiled it or dis- No, okay. Do you have your karmic causes and conditions? You got that? Got your karmic causes and conditions? Everybody? Okay. Anything else? Can I say something? One of the main karmic conditions of your existence is that you see things as external. You see things external not because you want to, but because of your past karma.

[09:53]

One of the consequences of your past karma and my past karma is that things appear to be external. Now, they have appeared to be external in the past, but just seeing things as external is not karma. Karma is action that you take based on seeing things as external. And when you see things as external and then you act on that basis, then the action has a consequence of making you inclined towards seeing things as out there on their own again. So, in a sense, what she said at the beginning is we only have our karmic conditions in some sense. We only have the karmic conditions, most of us, of seeing things as external, which is similar to saying we have the karmic condition of seeing things as having self. That's our karmic situation, and we only have that. We only have that. However, we also have, part of that only that we have, is we also have the karmic condition of hearing the teaching that we only have the karmic condition of seeing things falsely.

[11:08]

And we may have also the karmic condition of being able to hear that and accept that. Having to see and listen to, remember and accept. For example, the ancestors say, all sentient beings, that means all unenlightened beings just have karmic consciousness. Sentient beings do not have other kinds of consciousness. they have karmic consciousness. And karmic consciousness means consciousness which sees self in the world and in the person. Okay, now, did you want to carry on from there? How do you break out of that? Hmm? So there's a style about this, right?

[12:11]

The Zen teacher says to his teacher, or the Zen student, the Zen teacher says to his student, he says, all sentient beings just have karmic consciousness, or all sentient beings just have karmic causes and conditions. All sentient beings just have karmic consciousness, powerless and unclear, with no fundamental to rely on. How would you test this in experience? The teacher says to his student, and his student says, if someone comes, I say to him, Hey, you. If he turns his head, I say, what is it?

[13:15]

If he hesitates, I say, all Sinjin beings just have karmic consciousness, boneless and unclear, with no fundamental to rely on. And the teacher says, good. Now that's how he tests them and finds out that they're stuck in karmic consciousness. Okay? That example is how he tests people to see if they're stuck in karmic consciousness. He didn't say the following. If someone comes, I say to him, hey yo. If she turns her head I say, what is it? If she doesn't hesitate I say, congratulations sister, you just broke out. Didn't say that part. But in the commentary to that story they tell a slightly different story.

[14:26]

They take one person and they show that one person can have a back-out response and a stuck response. So... Nanyang is talking to one of his friends, and his friend says, in the Abha Tam Saka Sutra, it says that the fundamental affliction of ignorance is itself... the immutable knowledge of all Buddhas. The fundamental affliction of ignorance itself is the immutable knowledge of all Buddhas. This is the teaching of the Avatamsaka Sutra. Fundamental affliction of ignorance, that's a sentient being. Sentient beings themselves are Buddha. They don't realize it, but that's what they actually are.

[15:31]

And then the monk says, this seems rather difficult and abstruse. And the young Nanyang says, well, I think it's quite clear. Watch this. And there was a monk nearby, not even a monk, a young man who maybe wasn't even ordained yet that was in the neighborhood, and he was swiping. And Nanyang said to the boy, and the boy turned his head. And Nanyang said, is this not the immutable knowledge of all Buddhas? And then he says to the monk, to the boy, what's Buddha? And the boy hesitates, is perplexed, and stumbles off into the dust. And he says, is this not the fundamental affliction of ignorance? Do you understand the story? If the teacher says to you, hey you, and you go, that's what Buddha would do.

[16:37]

Say, hey you, Buddha, Buddha, turns. Not even saying yes, necessarily, just turns, hey you. Not even, hey you, Buddha, hey you. And you can respond to that without thinking that something's out there calling you, externally calling you. In other words, you're free of your karma at that time. But if somebody says, hey, you, and you think, oh, somebody is out there calling me, and I wonder who it is, et cetera, et cetera, then you hesitate, and you're caught. So this boy, first of all, he responded just like Buddha. So I just say, hey, you, if he turns his head, he's okay. Then I say, what is it, or what's Buddha? And then he goes, oh, what's Buddha, what is it? Something up there. He gets caught by externality. His karmic conditioning manifests. He's trapped. So usually we have our karmic conditions.

[17:39]

We are inclined towards being caught by the appearance of things being external. And yet sometimes somebody can do us a favor and say, hey you. And sometimes our karmic patterns do not manifest. Even that's all we have. our freedom from our common consciousness, which we don't have. Freedom is not something you have. Freedom is freedom from what you have. It can manifest. It can happen. You can respond like a Buddha if you don't happen to notice that you have a chance to respond as a Buddha and that that's out there as an opportunity. You just do. You just respond. Just like, you know, the rooms in the back side of the room here.

[18:40]

Do you see what's out there? Most of you aren't looking. What's the matter? You're frozen? You people who aren't looking are like, you know, that's the fundamental affliction of ignorance. The ones in turn then looked. Well, they looked at that moment. That's enlightenment. when you look there and say, well, what's he talking about? But the rest of you didn't turn your heads. You are what are called drug slurpers. Why didn't you turn? Oh! Good work, Oscar. Get the picture, Jane? That's how to break out.

[19:43]

Just respond before you have a chance to think of how to respond or who you're responding to. But in fact, everybody that calls you, you do respond to. And if you don't respond, if you don't suddenly realize that who's calling is external, you respond before you make them external, you just broke out of your karmic thing. So, hey you is kind of an easier opportunity than what's Buddha. What's Buddha? Will? It's dangerous for the spawn of that thing in the practice. It's dangerous to respond without thinking, that's right. And thinking first, it's not dangerous at all. It's just immediately tragic. There's no danger in that case. You just have screwed up. Now the next moment you're in danger again.

[20:45]

But the danger of that last moment you have manifested by thinking. You have just missed your life and plunged into your karmic hindrances, which is the most dangerous situation that a living being can be in. Just a second, I have to call on this guy. Yes? Oh, outwardly ceasing all involvedness. I guess I'd just like to expound where I'm stuck, still stuck, which is... Thank you for expounding being stuck. Sometimes I think there's something to be done about ceasing all involvements, and sometimes I think there's nothing to be done about ceasing all involvements. They just cease. Yeah? Thank you. Now, ma'am, miss, woman,

[21:54]

Sure, please do. So, the question is, is the wall not just plain blackboard or old? So she's wondering, what's compassionate about mind like a wall? Sort of. Yeah, sort of. I don't see much compassion in mind like a wall. But this instruction of mind like a wall is an instruction given by Avalokiteshvara.

[22:58]

The bodhisattva of great compassion gives this wisdom instruction. It's not really a compassion instruction. It's an instruction to purify your compassion of defilement. Many people feel compassion for for living beings. But most of the people who feel compassion for living beings are trapped in karmic consciousness. So they think the living beings that they feel compassion for are external to them. Therefore, their compassion is wounded and undermined by their misconceptions. Maybe there is a fly grown in Ulu. Yes. Yeah. Well, there is one thing or one way to look at it.

[24:00]

I take it out because it's not external, so the fly is weak. Yeah. Or I take it out because I... No, it's not the same. It's not the same. In the case of scooping the fly out and understanding that the fly is not external, you scoop the fly out, but you're not drained by your misconception. In the other case, you scoop the fly out thinking the fly is external to you and you gouge out your life and you gouge out your energy a little bit when you scoop that fly. And if you keep scooping flies like that repeatedly and each time you think they're external to you, after a while you're not going to want to scoop flies anymore. Matter of fact, you'll think the flies are killing you. It's not the flies that are killing you, it's the attitude that the flies are external to you.

[25:06]

Every time you help somebody and think they're external to you, it makes a little gouge in your energy. And after a while you have to run, the sutra says that bodhisattvas who help others lovingly thinking of them as other, outside themselves, they get burnout. Got dig, dig out, make a hole in, wound, make a leak. Like a leak in your energy. So after a while, you have to run away from the people you want to help because you feel like you're going to die. So then the very compassionate person who has this dualistic view has to take a big vacation from those people. And sometimes they just permanently retire. Not permanently, but take a long vacation. And they say, well, that shows what you get for trying to help people. They just take and take and take. I don't know if it burns up only the yang.

[26:14]

I haven't taken a survey on that. But anyway, there is a difference between the same action. Someone asked me a long time ago, and they said I said this, but anyway, I think it's good if I did. They said, how do you protect from burnout? And I said, Well, if you can sit down in a chair without expecting it to hold you, that's how you protect from burnout. Or open a door without expecting that it's going to open. These little assumptions that we make about things, these little expectations, they drain us. Same action. In one case it drains and in the other case it doesn't. So you sit down in a chair and you don't assume it's going to hold you.

[27:18]

You sit down and you see what happens when you sit down and you put more and more weight on it and pretty soon there's quite a bit of weight on it And then you feel like, I think I can lift my feet off the ground now, but I'm just going to lift up carefully. And there we go. Yeah, it actually can hold me. That way of sitting down. You don't get burnout. You may get fired, but you don't get burnout. Then every occasion of sitting down is a big deal, a big experiment, which you're going to try. And sometimes, of course, it does collapse under you, but you have, you know, so it's not primarily that the advantage of sitting down this way is that it protects you from falling through the chair, although that might happen, because actually you might get down there and it might collapse and you still might not have strong enough legs to hold yourself up at that point.

[28:27]

Does that make sense? It doesn't quite make sense to me. I was wondering if you could make another analogy as to what you're talking about to protect from burnout. You want me to make another analogy if you don't like that one? I don't dislike it, but I don't understand it. Well, I'll just go over it for a couple years and ask Bodhi Dharma questions about it and you'll get it. Try it. Try it a few times. Sit down the regular way 5,000 times and see what happens to you. I predict you will just collapse. You'll just die from that way. So stop before you kill yourself from that way. But if you sit down in the chair 5,000 times the way I just showed you, you'll feel fine. You'll get strong legs because you're gonna use your muscles when you sit down. You'll probably discover a new school, a new form of Chai Chi practice.

[29:37]

You'll have all kinds of interesting experiences that way. The other way, you're just gonna miss your life, [...] because you're living in the realm of expectation rather than actual experience. And you can stand that once a day, twice a day, 10 times a day, 50 times a day, with spaces in between. But if you consistently relate to things that way, you will just, you'll perish. Not just from old age and sickness, but from killing yourself, killing your life. But if you sit down, every time you sit down, it's a big experiment, a big mystery, a big adventure. You'll see the difference, try it. And notice that it's really hard to actually give yourself to sitting down in chairs as though this was like a meditation, a period of meditation. When you go to the Zendo and you sit on your Zafas, do the same thing there. I don't have time to do that.

[30:38]

I got to get on that cushion fast. I don't have time to like consider that I might fall through the Tan. I mean, I'm not going to fall through the Tan. Nobody's ever fallen through the Tan. All the time in the history of the Tan, I'm not going to fall through the Tan. Yeah, well, that's called being caught by karmic consciousness when you think that way. Some of you know this story. When I first came to Zen Center, I went to the president's office, and that wasn't his office, it was his house, and I went up to his house, and he said, please come over, and he said, you know, sit down, and he had these kinds of chairs, these kind of wicker chairs, and I sat down on the chair, and I went right through the chair all the way to the floor. And he said, you're quite dense. Aren't you? Now, did I assume the chair was going to hold me?

[31:44]

I think I did. But it didn't. So I didn't sit on it 50 times, 100 times, thinking... And when I sit in chairs and I don't, and when I sit in chairs and I assume they're going to hold me, I should confess a lack of faith in practice. I should confess I'm not following Bodhidharma's instruction when I sit in a chair like, oh, that chair's just going to sit there and that's going to be what I think it is. This is not Zen practice to sit down that way. And again, you can get by with this, you know, sort of, But you do that over and over. You do that a thousand times a day and you will not want to live like that again another day. You won't be happy. You sit down the other way, you'll be fine. Try it. I have a question about seeing things as criminals, which has to do with having a layer of pain that enters into

[32:55]

It's not really imposition. I mean, it's actually a flowering. It's a blooming of the, when you see things as external, actually the first thing that comes when you see them as external is you get scared. So everybody in this room that thinks the other people are external is afraid of those people. So then when you're afraid, then that fear then can bloom into hatred towards this person who's external, or it could bloom into attachment and greed towards them. Some way anyway, maybe greed, maybe attachment, maybe hatred will free you of this fear. It's not really the imposition. The imposition is the externality. Then the afflictions arise and they're not impositions, they're consequences.

[33:59]

They're really happening. So they're blooming of the fear you feel when you see other people's external. And the fear is the blooming of believing the externality. Any advice about how to do that? To work with the fear, the hatred. The hatred, confess it. Confess, you know, find somebody that you can confess it to. Sometimes if you feel hatred towards some people, And you tell them it's not appropriate because then they'll get so frightened, you know, that they'll, it won't necessarily benefit them. But try to find somebody else you can say, you know, I feel hatred towards this person. And that person can say, do you feel fear also? And you can say, yes. And they say, do you see him as external? And you can say, yes. So, confessing it over and over, you will gradually get to the place where the karmic hindrance

[35:06]

which sets up the externality, will melt. There are, of course, when you sit in a chair, you do not have to go with the assumption that's going to hold you up. You can say, okay, I'm not going to go with that. I'm not going to fall for that. I'm going to fall for my tendency to sit down that way. I'm going to actually sit down on this as though it is an impermanent thing. However, the sense of the chair being external is more profound and difficult to deal with. So that I have to confess. So there are lots of opportunities through the day for me to confess. I see this person as external. I see this chair as external. And if I see the chair as external, then I would like to make the chair permanent external. so I can sit on it.

[36:06]

If I see the people as external, I'm scared. There's many opportunities to confess that during the day, probably, for most of us. By confessing and repenting our belief that things are external, we melt away the root of the belief that they're external. But you can't necessarily confess to somebody that you feel hatred, that you feel hatred, but you can confess to somebody else who for the moment anyway you don't feel hatred towards. You're just afraid of that person. You're afraid that they're going to hate you for being such a hateful person. But maybe you can do it anyway. People do go and confess to people and there's a danger that that person will not like you for what you're confessing But there's also a possibility, although they don't like you for what you're confessing, they really appreciate that you're confessing. Because they really understand that you're in the process of becoming free from your karmic hindrance.

[37:10]

Karmic hindrance of seeing people as external. And then Judith? So picking up on Will's question, I have this sense that when I act without thinking that that's habit energy. And that's what it feels like to me. It can be. It can be that it's habit energy. And the appropriate thing to do is to kind of, you know, examine what I'm about to say before I say it or examine what I'm going to... examine my motives and whether or not this is appropriate before I actually act. But that's certainly acting with thinking. You said something about acting without thinking will be a habit.

[38:21]

Yeah, it feels like what's governing my actions when I act without thinking, when I act on an impulse, what's governing that is habit energy. If you act on impulse, it's habit energy. But when somebody calls your name and you turn your head, that may not be an impulse. In other words, when the doctor taps your knee or taps your wrist and your hand responds, that's action without thinking. It is not necessarily impulse there and it's not necessarily a habit. Because sometimes they touch you and you don't respond, and then they find that there's something wrong with your nerves, right? And you can't trick them usually unless you're a doctor, and you don't want to trick them anyway. They're just testing to see how your reflexes are, and they test you and you have a response. That's a response without thinking. That's a response without thinking.

[39:25]

That's a response that comes from the little hammer or the little finger touching you at a certain spot, and you're responding with no thought. And if you don't respond, if your hand doesn't move, that's also your response, and that shows the doctor that you've got a nerve problem. But in both cases, your response has no thought, and there's no impulse there either. When the teacher says, hey you, and the monk turns his head, that example is supposed to be one where they're not thinking before they move. They're not acting from habit. They don't have a habit of how to turn when people say, hey you. Now some people... who live in some monasteries might sort of like, if they're going around saying, hey, you all the time, they might develop a habit of how to respond to that exercise, right? Once you hear about this thing and you go to the monastery, well, that's a test, then you might get a habit of that. But most, I think he used that example as something he would try once with the person, maybe.

[40:30]

So that's an example where you don't think beforehand and it's not from habit energy. When he says, what is it? Then the impulse comes. Then the guy thinks, oh, what should I say? Then you get into like, well, should I say this or should I say that? And I shouldn't say, well, blankety-blank you, Mr. Zen teacher. I probably shouldn't say that. So once you get caught in this thing of thinking about what you're going to say, then you probably should think about it a lot. Because you are now turned into the poison system. And everything you say can be really harmful now. So now you should probably say, is this going to hurt anybody? If I have a good intention here? And this is called confused, hesitating, and stumbling off.

[41:32]

So as soon as this guy starts thinking, the teacher says, you just have karmic consciousness, boundless and unclear, and there's no fundamental to rely on. And you're sitting there listening, saying, I probably should not say any of this bad stuff that I want to say to him now. You know, because he's like belittling me, not respecting me, you know, making fun of me, you know, blurting over me, being the Zen master, I'm the crummy student, you're caught in all that, and it's probably good that you don't say any of that. But you might, after all that, you might say, would you like to hear what I've been thinking lately? And he might say, yeah, let's have it. And you could un-allow it, you know, because he's ready. And he or she, you know, they're hurted, and they say, how do you feel now? And you say, I feel much better. And you say, what happened there? And you say, that was karmic consciousness, boundless and unclear.

[42:36]

That was it. You're right. That's what you just showed me. Like that story of the Zen teacher who a samurai comes to visit him and he says, would you teach me the difference between heaven and hell? And he says, no. Because all you got is karmic consciousness, boundless and unclear. You'd never be able to understand any teachings about Buddhism, you moron. And the guy whips his sword out and is just about to decapitate the Zen master and he says, that's hell. That's hell. Then the guy drops his sword and drops to his knees and with tears of gratitude says, thank you, master. And he says, this is heaven. But he didn't think about dropping his sword and saying, thank you. That was like, hey, you. He didn't think about, oh, he's going to think this is really cool when I say this is like I'm so grateful. He didn't think that. That was an immediate response that was just like turning your head. That was an enlightenment.

[43:37]

That's heaven. When you just say thank you with your whole body and mind when somebody like helps you. You don't have to think about that. And you don't have to test to see how am I really thinking. It just gets out there, and it's not a problem. There's danger. It doesn't mean there's no danger. You might break your kneecap when you fall to the ground. You know? You might smell your mascara when you start crying. There's no big dangers. But there's no thought. That's the unethical knowledge of all Buddhas when he drops to his knees and says, thank you. That's Buddha. Right? And before, when the teacher was saying this stuff to him, he was thinking about stuff. And he didn't think about, he's a samurai, he didn't have to think about whether he's going to be harmful or not. So he just whipped his sword out. And fortunately the teacher said something before he struck him. But when you whip your sword out, I would suggest, please do consider what you should do.

[44:41]

But whipping your sword out means you're thinking. The most powerful thing you've got is your thoughts. Not the most powerful thing, but the most harmful thing is what you think. But if you respond before you think, like when somebody taps your knee and your knee goes up, your knee goes up there before you think. And it's fine. It's Buddha. You don't have to think about that. But if it's going up, you think, I wonder if that was a good response. That's the fundamental affliction of ignorance. And you think the response is something external. But that's not the disaster. When you notice that, then you start practicing again. Even when the doctor taps my knee, I'm sort of like wondering how I'm doing. The second ancestor talked to Bodhidharma, except I don't know where Bodhidharma is, but this kind of conversation about this teaching is what they did for seven years.

[45:44]

To work out what does it mean to not project, to not fall for the projection of independent existence on the world, which our mind impents. Our mind sends out the image of independence over the whole world. And then we're now being instructed to try to let go of that, but part of it is these kinds of conversations. Please, let's have conversations like this about this illusion for years and years until you can see that it really is illusion and you don't believe it anymore. And you're not afraid of people. Look at that smoke coming up there. And that wasn't a setup, there really was smoke. Sort of. Yes. I think I was kind of waiting, you're addressing the stress about having an idea.

[46:48]

I was beginning to hear you addressing that this concept of having an idea, as if it sounds to you right now, it's in this world of conflict, like every moment, there is a conflict, like this, you know, I have it, because every song, you see it freaks, there is no, there's just like a song, a song. Yeah, there really isn't habit energy. But what we mean by habit energy is that we think there's habit energy. There appears to be habit energy. There's not really habit energy. But because of our habit energy, which there really isn't such a thing, we see things in these stuck patterns. Like, you know, we see things out there on their own in a stuck way. They're really stuck separate from us. And we really have to do this. There really isn't that. Buddha doesn't see it that way. But we see it that way and that's the consequences of past actions performed on that basis. That when we do things based on misunderstanding, the consequence is that we tend to see things the way we saw them which led us to do these actions.

[47:58]

And even good actions Skillful action is based on duality. they make us still prone to see duality again. However, skillful actions, although they still support seeing things dualistically, they also support us being able to see that we're seeing things dualistically. Unwholesome actions, we see things dualistically, but we don't even see that we're seeing them dualistically. So still, good karma is good because good karma helps us see that even good karma is dualistic. Yes. Why do you use words to understand it? I use words to understand it. I use words to understand it. I use words to understand it. Could you say that again, please, a little louder?

[48:59]

Words. Words? Oh, well, because we have words in our mind. Our mind is, what do you say, our mind is kind of like infused with a tendency towards conventional designation, towards words. If we didn't have minds that were like tending towards words, we wouldn't need words to counteract our tendency towards words. If the meditation that you're doing is to see that the... This is a little bit complicated. I'll just see if I can see this quickly. In order to use words... we have to project self onto things that's a Buddhist teaching or I would say at this point anyway what we do is we project a self like I look at you and I put a little packaging on you and then I can say there's a man but the packaging I put on you is not really you

[50:28]

But because I'm predisposed, my mind is full of the tendency towards saying some words about you, I project a self on you, and projecting a self on you, I suffer. Now, if I could meditate in such a way that I could stop projecting a self on you, then I would take away the basis of the words. and gradually my mind would stop being infused with the tendency towards words. And then I would only speak when it's helpful. I wouldn't speak by compulsion. However, I don't know of any people who can learn the meditation of getting over the projection of self without hearing it through words because it's automatic to project the self. And you project the self because your mind also wants to be able to put words on things.

[51:35]

So you could say, well, I'm just not going to project the self, but your mind wants you to be able to talk. So it forces you to package things so you can put words on them. However, there is a meditation to stop believing the packaging and then you turn the whole process around and pretty soon your mind is not infused with the tendency towards words anymore. and you're a Buddha. And when you're a Buddha, then you can use words to help the people who are still caught in that trap. Bodhidharma didn't say much, but he basically was given instruction about how to take away the basis for habitual language. The Buddha doesn't speak out of habit, the Buddha speaks out of compassion. for those who are caught in the habit of language. But again, the habit of language is deeply imbued in us, but what we do is, rather than try to stop ourselves from talking, what we do is we stop ourselves from putting... The landing pad for words is the self.

[52:53]

We train ourselves to stop putting a self on things, and then our tendency, our compulsion towards language is relieved, and then we speak... not from compulsion, but from when it's helpful. You know, Shakyamuni means the silent one, you know, of the Shakyamuni clan. He was the silent one of the clan. He was a silent one and he talked a lot. But he really was silent. In other words, his mind was not, he wasn't speaking because of his habit to speak. He was speaking in order to help people. And if there was no people, his mind would be quiet. But when people showed up, he started talking. You people probably like me to give talk, right? Yes. Okay, here it is. But when there were people around, he was quiet. His mind didn't need to talk. His mind was beyond talk.

[53:54]

No words could reach his mind, ever. And with a mind that words don't reach, when people show up, he creates words to talk to them. Does that make some sense to you? Thank you for your question. Judith? Can we use words internally, like mantras or glabalani, to break the habit below of words? You can use words like mantras to take a break from the compulsion for language. But I think you have to not internally listen to teachings, not Durrani's, teachings in order to break the compulsion to language. Teachings about how you project self onto a selfless field. So the field of our life is this huge, not even huge, unimaginable field of interdependence is our life.

[55:03]

and we package it into little pockets and little categories so we can designate it. That's what causes our suffering. We need to listen to teachings about that in order to notice that and stop doing that. Dharanas or other types of exercises to stop discursive thought help you become calm. And when you're calm, then you can listen to these teachings better about how to stop agreeing with the appearance of self, which is necessary in order to speak. So Dharani's or meditating on your breath, but basically just giving up discursive thought. When you're saying Dharani and you're just saying the Dharani, or when you're tightrope walking and you're just tightrope walking, or when you're doing Qigong and you're just doing Qigong, and that's it, then Qigong's like a mantra. You're just doing emotion, nothing more. So at that level, you become very calm and concentrated. Or you could say you concentrate on the thing, but it means you give up thinking about how well you're doing at mantra chanting.

[56:09]

You can imagine somebody doing a mantra and saying, you know, I'm doing pretty well at this mantra. Yeah, this mantra's working. But there could be a mantra called, I'm doing well at chanting mantrams. And that's all you think about. I'm doing well chanting mountains. What is it? The mountain that people say, I'm doing fine, I'm doing fine, I'm doing fine, I'm doing fine. I'll be okay, I'll be okay, I'll be okay. If you could actually just stay with that, you would be okay. You'd be calm. If you could actually like, I'll be okay, but what if I'm not? I'll be okay, [...] I'll be okay. Sounds like Amida Buddha, Amida Buddha, Amida Buddha, I'll be okay, Amida Buddha, I'll be okay. If you can actually do that without thinking, how much longer should I do this? When is it going to work? All that stuff. This is really stupid. I'm becoming a cult figure, whatever. If you're ready to stay with anything like that, you will calm down. Once you calm down, then you can listen to the teaching, which is gently telling you how you're screwing everything up.

[57:14]

And then you can see how you're screwing it up. You can see how you're projecting externality. You can see how that gives rise to affliction. And then you can see how it tells you, if you just keep watching this, you'll stop doing that. You'll stop holding to things being what you think they are. And you can do that better when you've maybe done mantras or whatever for a long time so you got really concentrated. But we need to understand selflessness, which means we really have to stop. Understanding selflessness means, or understanding no self means you really stop believing the appearance of self, which your mind still projects out. The Buddha can actually see that there isn't, can actually look at things without projecting a self onto them. Brani Sattvas can do that too, can actually look at things without projecting self on them, but then they can switch back to projecting self and not believe it. So in the Heart Sutra, Avalokiteshvara sees selflessness of phenomena, and at that time he doesn't see any phenomena.

[58:20]

but then you can switch back to seeing phenomena with the self, but then after you see no self, you don't believe the self anymore. And you just go back and forth, back and forth. When you're hearing these teachings, Paul, and hearing these teachings, your mind is actually working towards your liberation. Now your discursive thought is working for liberation before your discursive thought is distracting you. Now you're concentrated and you used your discursive thought to apply the teachings to what's going on. The teachings say, please notice what you're doing. Please notice how you're putting externality on your friends. Please notice how that gives rise to affliction. And you look and you'll see that's what the case. You'll see, you can see. Many of you can see that when you see people out there, you're afraid of them. And when you take a break from that, you're not. And you can take a little break sometimes. And your body actually is a lot of times not acting that way.

[59:22]

Like when saliva comes. You don't think and then salivate. It just comes. But sometimes we do think, and then you can see, thinking of things as external, we become afraid. Coming into a room of people and think of them external, you're afraid to give a talk. If you remember that they're not external, you can come and give a talk. Which is similar to some people say, I'm supposed to give a talk, but I'm just going to remember that the people there, some of those people are my friend. And I got my friends in the front row. So now I can dare to give the talk because my friends are kind of like not other than me. Right? Your friends are kind of like not exactly external. Right? But even if you make your friends a little bit externally, you're just even afraid of your friends, which is really sad. Even afraid of your children and your parents and your spouses and your teacher and so on, because that little sense of externality.

[60:27]

That's why we have to give it up in order to enter the way. So if you want to practice compassion, that's good. And then you have to also bring wisdom to it to purify your compassion of seeing all beings that you love as external. Doesn't that make sense? Will we have to do that? What's the matter with you? Why are you making that face? Just kidding. I don't ask why questions. So you say that genuinely... ...is like... Genuine spontaneity is interconnectedness and genuine uptight being frozen and scared is interconnectedness. Everything is interconnected. When you're totally uptight and afraid and thinking everybody's your enemy, that's interconnectedness.

[61:29]

However, you don't realize it at that time. And again, spontaneity needs to be based on commitment to compassion. So again, I'll stress this one more time before I stop. Bodhidharma is avalukiteshvara. Bodhidharma is the person who is totally devoted to the welfare of other beings before herself. And that person teaches vast emptiness, no holyness. says all external involvement. That's what Avlaka Teshvara teaches. That's what compassionate beings, if you have been this teaching without being devoted in compassion, without having a deep commitment to the welfare of other people, this teaching is not appropriate for you. So you're, and if you start practicing this and you feel your compassion is getting slippery or sliding away from you or getting weaker, you should stop this practice and go back to check out to make sure you're really devoted to other beings.

[62:29]

other beings, who you're trying, who will, after you realize you're devoted to other beings, then you can take on the practice of realizing that the other beings are not external. They are other. They're not you, but they're not external to you. They are you. But that has to be based on compassion. That wisdom practice. Does that make sense? Okay. So maybe we can just about stop after long. Good question. Sounds like hustle is the same as in the past. In that if you push everyone to do the economy part of that and want to be compassionate, it takes a lot of time. So what is it that you're trusting?

[63:40]

You're not trusting the people, what are you trusting? You're trusting compassion. You're trusting that compassion is a good idea. People aren't trustworthy, but compassion is trustworthy. And then we just need to purify the compassion of any infection of duality, which is the huge job to get over externality while we're practicing compassion. It took Hoika seven years to get it worked out. Please, please, please work it out. I think you're compassionate, but I don't know if you understand this emptiness thing yet. So please work it out with each other.

[64:42]

Practice it. Check it out. May all intention be revealed.

[64:53]

@Transcribed_UNK

@Text_v005

@Score_90.81