You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to save favorites and more. more info

Fathers and the Three Natures

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk explores understanding phenomena and the complex nature of fatherhood, utilizing a teaching that all phenomena possess three distinct natures: conceptual, dependently co-arisen, and thoroughly established. These concepts underscore the illusion of permanence and the realization of freedom through understanding causation as beyond conception. This framework is applied to reflect on fatherhood and the speaker's relationship with their father, poetically examined through stories that highlight love and respect beyond conventional ideas.

Referenced Works and Figures:

- John Cheever and Ben Cheever

-

Used to highlight familial relationships and father-son dynamics, reflecting the need to love and respect despite imperfections.

-

Buddhist Teachings on Causation and Phenomena

-

Central to the talk, illustrating the transient and dependent nature of experiences and their application to everyday relationships, including those with fathers.

-

Bateson's Anecdote in Japan

-

Provides cultural insights into respecting fathers as a practice, independent of the father's personal attributes or worthiness.

-

Suzuki Roshi

- Mentioned as a paternal figure giving teachings that fill the gaps left by biological fathers, illustrating how spiritual teachings can supplement familial roles.

The talk implicitly draws from the Sutra on the Three Natures, emphasizing the interdependence of all phenomena and the need for wisdom in relating to others, particularly in familial settings.

AI Suggested Title: Fathers and the Three Natures

Possible Title: Sunday

Additional text:

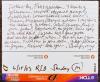

Additional text: Fathers Day, Feast of wisdom. 3 Aunts of phenomena; inpui, element, havent established. Convention would answer. Dream, mysteries, absence of dean & missing the realm of freedom. John Craven. Bets our future, handwriting too good. Nice body with weak blunt. Suzuki Roshi gave gifts that red bad couldnt. When I bet my head you scream. Full trip to pure states. Gregory Bateson in Japan, Respect - look again, Changji, very fast, Love is the unitys object beyond our ideas - mysteries, oven - dependent, George Bush, Loving while not liking, Dads friend.

@AI-Vision_v003

Today is a day that some people call Father's Day. I, part of me wants to say something like congratulations to all the fathers, but another part of me doesn't want to say that. Somehow it's easier for me to say on Mother's Day congratulations to all the mothers, but there's something about fathers that the congratulations doesn't come so easily. But I do feel fine about setting a table for a feast of wisdom

[01:25]

with all the fathers and all their children. I do want to realize love for all fathers. Now, I said in the table, I put on the table of the feast of wisdom, a teaching for each person at this table of wisdom, and the teaching is a teaching about the nature of all our

[02:29]

experience, the nature of each of our experiences. And I hope that this teaching will help in our consideration of how to relate with the father. The teaching is that all phenomena has three characters, or three natures. All phenomena have a conceptual nature, a nature which is conceptually imputed to every experience. All phenomena have a dependently co-arisen nature. All phenomena have the nature that

[03:33]

they arise in dependence on things other than themselves. And all phenomena have the nature to have a thoroughly established nature, have a thoroughly established way that they are, always. And the way everything is, the way every experience, every phenomenal experience, every empirical experience, the way it is, is that the experience, that in the experience as it's actually happening, there is an absence of all and any of our conceptions about what's happening. So once again, when our life arises for us, it really does, and it arises in dependence on things other than itself. Our life arises

[04:42]

moment by moment. It's given to this world, and we can enjoy it moment by moment. And it's given in dependence on things other than itself. And in this life, this rapidly changing flow of life that arises through the power of things other than itself, in that life, there is an absence of anybody's idea about it. However, we do have ideas about it. And when we mistake our ideas about our life for our life, the conventional human world arises out of the combination of what's happening, our actual

[05:47]

life, as it's happening, independence on things other than itself, and taking it as our idea of it, we get the conventional world, this one, where there is time. And when there is, therefore, because of this belief that our ideas about things are what they are, we feel greed for them and hate for them. And we try to do good in this conventional world, but we can't really do much good here, because of all the actions based on a belief that what

[07:02]

we think is happening is actually what's happening. We must open to the world of the way things are actually happening in order to allow good to be realized. The table is being set. A few more name tags to put at your place. I could say it this way, which is a little bit dangerous, but I'll say it this way, that all of our experience has three characters, which I could rename as a dream character, a mysterious character, and a character which is the absence of the dream in the mysterious character. The dream

[08:16]

character is here, creating this phenomenal world, but at the same time, this dream does not reach the way things are actually happening. The way things are actually happening is free of the dream of how they're happening, it's free of the dream of what is happening, and because the way things are happening are free of all dreams, the way things are happening is freedom. This is the realm of freedom, and this is the reason why re-freedom is possible. Buddha teaches that the way things are, the way we live, the way we are moment by moment is a causal phenomenon. The Buddha teaches basically a teaching of causation about our life, but he also teaches that this causation is beyond any conception of the causal process,

[09:28]

and that's why the causal process is free. That's why we can be free of any phenomena, because all phenomena are caused. Now I'd like to apply this teaching to today, Father's Day, and mention, start off by mentioning that the founder, the person who conveyed this teaching to us, and this person's disciples, male and female disciples, this person was a father, and he loved his father, and he

[10:36]

left his little boy. According to our story of him, he was a married man and a father who left his son. So there's a little bit of a problem here, that we're, I don't know what, we're disciples of a deadbeat dad. However, although he didn't, although he left home, he left his son in a palace, which, so, actually maybe deadbeat isn't the right word. Playboy dad? Absent dad. So he went off and realized that his son was a playboy, and practiced the way of enlightenment, and then he got back together with his son, and his

[11:42]

wife. Right? Did he get back with his wife, somewhat? As a disciple, they practiced the way together. And he got back with his, the woman who served him, and he got back with many years as his mother. As I was driving from Zen Center's monastery, Tassajara, on Friday, up here, I listened to the radio and there was a show about, a Father's Day show about kind of talented men with talented fathers, or talented sons of talented fathers. And one of the things I heard in the program was something said by a man named Ben Cheever, who is a

[12:51]

son of John Cheever. John Cheever is a, I think a Pulitzer Prize short story writer. His son's also a writer, and his son has now edited some of his father's letters, and made a book out of that. And one of the things he said, I think, this may not be accurately remembered, but one of the things he said was, his father said that his father had certain drawbacks, certain shortcomings, which I think he admitted somewhat to his son, not all of them, but some of them. And he said to his son, I think, love me with all my shortcomings, and limitations, and find other men to be your father in the ways that I can't be.

[14:03]

Now this struck me because, although my father didn't say that to me, in fact, that happened to me. That my father stopped living with me, and that was the first thing that struck me. My father stopped living with my mother, and brother, and sister when I was about 11. So after that I didn't see him, well anyway, he didn't live with me. I did see him quite a bit, but he didn't live with me. I'll tell you about how I saw him. But when he left, I didn't actually feel like I was going to look for other men to be a father in this, in this kind of void created by his departure. And I didn't think consciously that I was

[15:13]

looking for men who could offer to me the things that he couldn't. But in fact, men did come forth and father me, lots of them. I don't know why I was so fortunate, but a lot of them came forth and brought me those very things which my father couldn't give with me, give me, even if he was home still. Now talking to you right now, I think, actually, that his leaving, actually, might have made it easier for me to love him, just love him, and care for him, and not slip away from loving him, because he couldn't give me the things

[16:14]

that I needed. If he had been there in my face all the time, I might not have been able to love him, or he might have made it difficult for these other men to come forward and give me the things that they gave me. But he did give me some good things before he left, and some good things after. In a way, one of the best things he gave me was to show me who he was, in the sense that he didn't have much discipline, he was an undisciplined, relatively

[17:22]

undisciplined person, at least the way he appeared to me. One of my girlfriends said, �Your problem, father, is that he's too good-looking.� I always thought he was really good-looking, you know. My mother was pretty cute, but I always thought, �How come she got to be married to this handsome guy?� To me, he looked like Superman, like, you know, in the comic books, he had that kind of face. And he didn't have that kind of blue-black hair, he was kind of bald, but when he had his hat on, and you didn't notice the bald head, he had this really handsome face. And he was, you know, quite a bit bigger than he was, 6'2". Anyway, he was really a handsome guy. I would say also today that he was too gifted, and therefore he never really disciplined himself. And I saw, I got to see, what it's

[18:36]

like, how your life goes without much discipline. He showed me what happens. He showed me what to do. And of course I saw that in other people too, but to see it in my own father was really quite a gift for him to show me that. One time he came to Zen Center, after I'd been here for about seven years, on the verge of my marriage ceremony, he came out for the wedding, and he came to my room, my room is the room which is now the abbess's room, I used to live in that room, and he came into my room and he saw my altar, and on my altar I had a picture of my teacher who had died three years before. And he said, you know,

[19:42]

he looked at the picture of my teacher and he said, he was your real dad, wasn't he? And I think I kind of quietly said, no, you're my real dad. My father gave me a really nice body. It comes with a kind of a heart that's susceptible to heart attacks, but otherwise it's a really good body. He died when he was sixty-two, and I'm a few days away from sixty. So, that's another gift he gave me, the gift of awareness of my life may end soon. Will

[20:50]

I get to sixty-two? I'm watching, day by day, wondering. And if I make it to sixty-two in the past, then I start to wonder, will I make it to sixty-seven, where my Suzuki Roshi got to sixty-seven. So they give me these gifts by, you know, really impressing on me their mortality. But Suzuki Roshi did give me things that my father couldn't give me. So in a sense, although I wouldn't say he was my real dad, he was definitely my dad in the way that my biological father couldn't be. And then after my daughter was born over

[21:55]

in this building with the slanted roof, she was born in that house, he came to visit to see her. And he was sitting in that house, and he looked at me and he said, Rebi never abused his body. In other words, you never abused your body the way I abused mine. He really abused his body. He had a great body, and he just didn't take care of it. Smoked and smoked and smoked and drank and overeat and no exercise for forty years. The first eighteen he took pretty good care of it, but after that he really abused it. And it held up, but finally it collapsed. And he looked at his son and said, But my son didn't do that. And I thought, Thanks to you, that's why I could see how a great body can be harmed

[23:09]

by not caring for it. I also thought, you know, one time, you know how mothers say to their sons or daughters, Wait till your dad gets home. You know, you're being naughty. And they say, Wait till your dad gets home. I'm going to tell him and he's going to discipline you. So one of those times that happened, and my dad came home and she told him about it, and I don't know if she ordered him to or not, but anyway, he took me upstairs to my room, and he took out, I was about eight or nine, and he was this 250 pound guy, and he took out this, I think he maybe took out some kind of a brush or something,

[24:11]

and he came over to me and he said, Now, when I hit my hand, you scream. So he took the brush and hit his hand, and I go, Ahhhh! Ahhhh! So I felt a little sorry for my mom, but I actually thought that was kind of an appropriate way to punish me. It was a punishment. We did the thing. It just didn't hurt very much. He could have hurt me, but he didn't really hurt me, he just sort of like did that way. And another time, which I mentioned recently, around that same time that that happened,

[25:15]

I was playing with my toy soldiers in the living room or something, and my parents said to me, Where did you get all those toy soldiers? Because there was quite a few of them. And the floor was covered with them, and they didn't buy them for me, so they wondered where I got the money to buy these soldiers, or was it a donation? So anyway, at our school, we had this children's savings program where you would bring some money to school, and then we would put them in a deposit envelope and send them to a bank called Farmers and Mechanics. Remember that one? This is in Minneapolis, they have Farmers and Mechanics Bank. So anyway, I said, I didn't make my bank deposits. And then they looked at my bank book, but

[26:22]

I actually had made my bank deposits. So then I told them, I said, I stole them from the dime store. And it wasn't one big heist. It was many little ones. So, my father took me for a little field trip to the police station. This was like, not the downtown police station, but like a substation near our house. And so we went into the police station, and my father said to the person there, the clerk, he said, could I show my son your cells? And the guy said, okay. So they went in to look at the cells, and in

[27:24]

this particular jail, there were no people in the cells, there were just bicycles. So, he pointed to the cell, he said, would you like to spend some time here? And I said, no, thank you. He said, well, this is where you might wind up. And he said, you know, and then, I don't know if I said it right then, but he said, you know, I stole things when I was a kid. So, he said, you know, I don't know if I said it right then, but he said, you know, it would really kill your mother if you went to jail. So, my father, with me anyway, he didn't come on to be, you know, like, I'm perfect, you be perfect too.

[28:27]

Or, I'm perfect, how come you're not? That wasn't the way, anyway, that he taught. And then, like, just a couple years after that, he was out of our house, because of being so good looking. Many people besides my mother wanted to be his girlfriend. So, my mother didn't want to go along with that, so he left. But he continued to love me for another 25 years, and I continued to love him.

[29:28]

Knowing his limitations, and feeling sorry for him, because I felt like he, you know, he was a businessman, and I felt like it was so sad that he was a businessman, because really, he didn't want to be a salesman. He wanted to be a piano player, or a college professor, or something like that. He wasn't suited for that kind of work. I always felt sorry for my father, because of that. Always means from around 11 years old, or 12 years old. I heard from him, and I was like, I'm not going to do that. I'm not going to do that.

[31:01]

Gerger Bateson one day, he told me about, he was doing some research in Japan, anthropological research in Japan, and he was talking to a Japanese, a young Japanese woman, and she said something like, I think she might have said something like, we respect the father. Like, we respect the father, or I respect my father, but somewhere in between there, like, we Japanese practice respecting our father, the father. And he said, well, he said maybe like, do you respect your father? And she says, yes. He said, well, is he respectable? And she said, no, not really. We practice respect for the father for ourselves, not because our father is worthy of it.

[32:05]

We respect, we pay respect as the appropriate practice, rather than being concerned with whether the person has the qualities that you would respect. So, in suggesting that we love our father with all his shortcomings and limitations, that doesn't mean we're being instructed to like our father or dislike our father. Liking our father and disliking our father is being caught by our ideas about our father. Respecting our father, respecting anything, means look again.

[33:19]

And look and remember that what you're looking at, the man you're looking at, the man you're thinking of, the man you're remembering, the man you're meeting, has a character, a basic character, which is that he exists. The way he is, actually, basically, is that he's changing very fast. He's changing very fast. Looks like the same old buzzard, but he's changing very fast. Looks like he's that same guy that we thought such and such a way about yesterday, but he's changing very fast, and the way he is, he doesn't make himself be that way. He's not that way by his own power.

[34:30]

The way he is arises, for a moment, in dependence on things other than his poor self or his great self. Whatever kind of self you think he is, however he appears to you, he has a basic nature, which is that he doesn't make himself, and other things make him. And the way they make him is mysterious in the sense that it's inconceivable, there's no way we can like imagine it. We can hear the teaching about how our father is and how anything is, how our mother is, how our brother or sister are, how our children are, how our spouse is, how our teacher is, we can hear the teaching about the way they are.

[35:33]

They all depend on things other than themselves to exist, none of them make themselves, but our ideas about how that goes don't reach it. That's why the way they are and our relationship with them has the potential of being free and peaceful and joyful and healthy. So I call it mysterious, but I'm not suggesting you try to get a hold of what the mystery is, but listen to the teaching, remember the teaching when you meet your father, the teaching that the way your father is, is due to things other than himself, and your ideas about how he is don't reach him. Now this way of being with your father, I suggest, is learning how to love him with

[36:49]

all his limitations. He is limited, but he's also free, if you can understand him, and you are free with him. And this is a little tricky too, but I would say that just as your father has this other dependent character, this other powered nature, that love also has other dependent character. Love also arises in this world, moment by moment, and love is also something that doesn't

[37:53]

make itself happen. In a sense, love is the way things exist. Love is the mysterious way things exist beyond our ideas, and the way things exist beyond our ideas is love. Love, the way we actually are giving life to each other, is our other dependent character, and in a sense, that is also what love is and how love is. So love is also our fundamental nature and is beyond our ideas about what love is. By being mindful of this teaching of our basic nature, we can realize our basic nature and

[38:59]

realize love, which is already happening, it's just that we have a powerful tendency, a powerful leaning to misconstrue what's happening as our idea of it, to misconstrue love as our idea of it, and therefore to say, for example, this is not love what you're doing, or I don't love you, or I do love you, and you think that the way you love the person is the way you think you love them. I am dependent on you, you are dependent on me, I have a loving relationship with you,

[40:00]

you have a loving relationship with me, but I don't know what it is, in terms of my conceptions. That follows from being convinced of this teaching, that way of feeling, and this is a way to love people, even our father, no matter how limited he is, our father is our father, we all have a father, we are all intimate with our father, and our intimacy, the way we're intimate, is beyond our ideas of how we're intimate with our father, even though we may have some really nice ideas about how we're intimate with our father, we also have some ideas about how we're intimate with our father which we don't like at all. Those ideas, positive or negative, don't reach our intimacy with our father, but they do

[41:06]

give us a way to locate our father, to identify our father, so we have a conventional world, there's something about that we have to live with and be honored that too, so we're not trashing our ideas, we have to accept them and work with them, but remember they don't reach their referent, they don't reach their source. So, even though I say that the way you love a person or yourself or a flower or an animal is beyond your ideas of it, beyond my ideas of it, beyond Buddha's ideas of it, and even

[42:08]

the description that the way things are is that they depend on things other than themselves, still that idea doesn't reach them either. So I'm suggesting that the practice of learning to love is to listen to this teaching and be mindful of this teaching all the time, actually take it back, it's to practice this teaching and be mindful of it in each moment, and then if you're not, then you're not listening to the teaching. I guess if you listen to the teaching enough so it really becomes you, then you don't have to be mindful of it, because you just are totally convinced, so then you always remember when you see someone that they're not what you think they are, and you're always open

[43:12]

to this loving way that every person is and the loving way all your relationships are. So I know some people who don't like some people, do you? For example, in the Bay Area, I know some people who don't like George Bush, they don't like him, and they think that they don't love him, alongside of that not liking, they think they don't love him. Some people, however, actually, I think, think they don't like George Bush and think they do love him. I think that's possible, that you could actually think you don't like someone and actually

[44:13]

get into it, not liking them, and realize that's happening in the conventional world, you don't like somebody, you're really repulsed by someone, you find someone really obnoxious, and at the same time remember this teaching and say, but I love them. I'm actually in a loving relationship, and the way it's manifesting is I say, I do not like you, but I say that in the context of our loving relationship, which I don't know anything about, but I've heard in the scriptures that we have that, and I'm mindful of this all the time, and some other people you say, you know, I really like you, just so I mention that, but this is not very important, what's important is that I love you, and that you

[45:17]

love me. What's important is that we actually are together in an intimate way that neither of us have the ability to imagine. I mean, we can imagine it, but our imagination doesn't reach our relationship, and I'm mindful of that, and in that way I'm practicing love with you. But I do like you sometimes, like right now, and now I don't, like right now, and I recognize that. That might be clear for all I know, what I just said, but anyway, my idea of it being

[46:19]

clear doesn't reach it. Whatever happened here this morning, my ideas of what happened here this morning don't make it to what happened here this morning. And my idea that your ideas don't make it also don't make it to your ideas, or they're not making it. Therefore, if after the talk people say, well, that was a good one, I go, now listen, what's the teaching again? Oh yeah, let's see now, they say it's a good one, and what is it again, that talk, oh, it was something that happened in dependence on things other than itself, and neither of us know what it is, but he's saying it was a good one. And that person over there is saying, you know, it wasn't a good one, okay, all right,

[47:27]

let's see now, it wasn't a good one, now what's that? Oh, somebody's saying it wasn't a good one, what's happening? What's happening? I don't know. Let's see now. Oh yeah, what's happening is arising in dependence on things other than itself, and it's beyond my idea. Yeah, something like that. But it's a little hard when they say, that was a good one, to sort of like, you know, what's the teaching now, what teaching do I use to accompany me with this experience so that I don't grasp it as what I think they're saying and get greedy for more, or

[48:30]

if they say it's bad, I don't grasp it and hate them for criticizing me, for not appreciating me, I hate them because I think they're not appreciating me and I believe that as actually what's going on. You have to listen to this teaching a lot so it makes enough impact so you actually can be present with it in the midst of the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. I spent quite a bit of time today rubbing the tips of my fingers against the edge of

[49:57]

the metal at the corner of my little thing here, I kind of miss having used my arms more. Anyway, I think that's probably enough on this business. I couldn't really think of an appropriate song, but then I thought of one I thought might be kind of okay. What were you thinking? Oh, My Papa. We can do that, can I do one before that? Okay. What I thought was... Old Man River, that old man river.

[51:08]

He just keeps rolling, he keeps on rolling, he just keeps rolling, he keeps on rolling along. He don't plant taters, he don't pick cotton, and them that plant some is soon forgotten. But old man river, he just keeps rolling along. You and me, we sweat and toil, body all aching and wracked with pain.

[52:16]

Tote that barge, lift that bale, get a little drunk and you land in jail. I get weary and sick of trying, I'm tired of living and scared of dying. But old man river, he just keeps rolling along, rolling along. Now, do you know Oh My Papa? You don't know it. Well, I know a little bit of it. This is Perry Cromer, right?

[53:18]

Oh my papa, to me he was so wonderful. Oh my papa, to me he was so grand. Something like that. In 1977 I was taking a bath, splish-splash I was taking a bath, along about a Saturday night, and my telephone rang and my wife brought it to me and gave it to me, and it was my brother, and my brother said, Dad died. And I said, OK, thank you, I'll come from San Francisco to Minneapolis. So I went to Minneapolis with my wife and my little baby girl, and we went to the funeral home, and it was one of these, he was an open casket,

[54:29]

so I think I walked into this room, I remember it being kind of light-colored, and I think up by the, where his body was, I remember it being kind of like pink or something around there, but anyway I walked up to this casket, and I went to look at him, I don't know why I went up to look at him, but anyway I did, and I looked at him, and I just burst into big, big, big tears and sobbing. He looked so, he looked so sweet, and I remember it really, he always was really, really, basically such a sweet guy, he just lacked discipline. But he was so sweet, really, and you could just see it, that's all I could see when I looked at him, and I was crying and crying, and I was totally, I wasn't expecting to cry, I hadn't cried when I heard,

[55:31]

I didn't cry on the airplane, I just saw him and I just burst into tears, and I felt so good, I felt so good crying, I could have cried all night. But then my uncle came up to me and said, it's okay, it's okay. So I kind of had to stop for my uncle's sake. But I wasn't crying because my dad died, really, I cried because he was so sweet, so moving, that this big guy could be so sweet, and you could just see it, that's all it was, just big, sweet guy. Sometimes it's hard to appreciate that big, sweet, loving thing that's there because of our ideas about him. But I say sweet, but really it's something much all beyond that too.

[56:34]

So please take care of everybody, okay?

[56:42]

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ