You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Compassionate Living Beyond Strict Rules

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk explores the evolution of Buddhist precepts, namely the Vinaya, Bodhisattva precepts, and the concept of Qing Gui, emphasizing the balance between personal purity and compassionate conduct in Buddhist practice. It discusses the historical context and practical application of these precepts within the Zen tradition, highlighting their role in promoting appropriate relational behavior rather than strict adherence to rules. Additionally, the talk emphasizes practicing together in monastic settings and encourages creative adaptation of precepts to contemporary practice.

Referenced Texts and Works:

-

Vinaya: A foundational set of monastic rules for Buddhists, including different guidelines for monks and nuns, as well as precepts for laypeople; central to discussions on personal conduct and purity.

-

Bodhisattva Precepts: Emphasize compassionate behavior; the focus is on the relational aspect rather than mere abstention from negative actions.

-

Brahmajala Sutra: Contains a version of Bodhisattva precepts listing 58 precepts, with a particular emphasis on not profiting from selling intoxicants; influential in the Zen school.

-

Qing Gui: Pure rules developed by Chinese Buddhists, particularly Zen monks, aiming to reconcile personal purity with compassion.

-

Bai Zhang Wai Hai: Credited with creating a set of pure rules (jing wei) for monks emphasizing an approach that respects but is not restricted by existing precepts.

-

Dogen Zenji and the 16 Bodhisattva Precepts: Although initially trained in the Kendai tradition which utilized 58 Bodhisattva precepts, Dogen transmitted a modified set of 16 precepts in the Soto Zen tradition, highlighting a creative adaptation for contemporary practice.

Relevance to Zen Philosophy:

- The talk is relevant to understanding how Zen Buddhism integrates various precepts into a cohesive practice focused on balancing rules with compassionate living.

- Emphasizes the importance of adapting historical precepts to modern contexts and the collective practice in fostering an environment conducive to spiritual growth.

AI Suggested Title: Compassionate Living Beyond Strict Rules

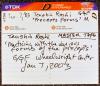

Side: A

Speaker: Tenshin Roshi

Location: Green Gulch Farm

Possible Title: Practicing with the various forms of the precepts

Additional text: Master Tape, GGF Wheelwright Center, Precepts Forms M

@AI-Vision_v003

In the history of the Buddhist tradition, in the early days there was a set of what might be called codes of conduct that the Buddha gave to disciples and primarily to monks and nuns. But this code of conduct was also extended to lay people. The name for this whole code was Vinaya. For monks, there were different presentations of this code of conduct, but for monks it comprised major and minor guidelines of personal conduct.

[01:08]

There were about 250 rules, or guidelines for monks. For nuns, there were about 340 rules. And for lay people, it was generally speaking five, unless they were on monastic retreats and then eight. The five for lay people were not killing, not stealing, not misusing sexuality, no intoxication, and then when they went into a monastic retreat, they would add on to it, I think, not sleeping on a high platform, and not wearing jewelry or something. Anyway, those regulations, those guidelines for lay people were something like that.

[02:21]

For men and women it was the same. And these precepts, generally speaking, they look like what they're about is personal purity. They're about how to personally suppress one's own unskillful or even wicked conduct. Then another type of precept emerged in Buddhism, which are sometimes called Bodhisattva precepts. B.S. with a circle around it.

[03:22]

It's not the Bodhisattva precepts. And these precepts were not so much about personal purity or about suppressing one's evil conduct. They were more about, basically about, they were basically concerned with compassion for others. So if you listen to these precepts, they might sound like suppressing personal wicked behavior. For example, not killing is one of them. But the emphasis was not on you becoming like the perpetrator of someone's guilt,

[04:25]

but rather you not taking the blunders. Not so much you becoming like someone who doesn't steal, but rather you being the one who has that kind of relationship. And so the Bodhisattva precepts didn't necessarily sound so different. It's also another one that's not to take life. It's also one of many of these precepts, but the emphasis was not on purity or purity, but that not taking life characterizes the relationship for the consent of compassion. So another example is that in one presentation of Bodhisattva precepts, which was rather influential, particularly on our Zen school,

[05:27]

Bodhisattva precepts were presented in this picture called the Brahmajala Sutra. There's a Pali Brahmajala Sutra also. There's a different sutra. This sutra is about the transmission of the Bodhisattva precepts. It's more than just a list of precepts. Part of the sutra actually lists 58 precepts, 10 major and 48 minor precepts. If you'd like to see a copy of the Bodhisattva precepts I've presented in this description, you can see them in the description box. The major precepts of the Brahmajala Sutra include one, which is not to sell intoxicants.

[06:39]

So that tells you the difference. It's not about you not doing it, of course. The major precept is not to sell, not to make a profit on selling other people something that's not necessarily good for you. There's also a minor precept in the 48 about you not doing it. But again, the emphasis is not so much on you becoming a wonderful ketoter, but rather that you wouldn't drink because drinking might not promote your having a pleasant relationship, beneficial relationship. But putting the not selling here first, you can see that the point here is what's good for other people. Of course, you following practices which you don't think people think, is not cut off from doing what's good for other people.

[07:43]

There's an emphasis here. So again, the emphasis here is individual purification, avoiding evil. Here the emphasis is on compassion. And then in China, another form of precepts developed, which are called, in Chinese they're called... Qing Gui, in Japanese they're called Shin. And Qing Gui means pure rules or pure standards. And these precepts are an attempt on the part of Chinese Buddhists,

[08:47]

especially Zen Buddhists, to reconcile the apparent contradiction between precepts about individual purity and precepts about compassion. The emphasis in these regulations is to guide, starting with monastics, that these pure rules were originally for monastics. But also remember that in the early days of the Mahayana, the precepts were for monastics also. The Mahayana Buddhism didn't just go outside the monastery. But these precepts were particularly for monastics. But they weren't really seen like the Bodhisattva precepts, or the Vinaya precepts alone.

[09:51]

In the history of Zen, there's a very revered name, which is Bai Zhang Wai Hai. I don't know if there ever was such a person, but we do have a name like that. We have a lot of data, but that name is highly revered. People actually thought there was somebody by that name, and that person's name had a very good reputation. It was a great Zen master. One of the things he did was he made up a jing wei. He made up a set of pure rules for monks. And he said that the regulations and the way of living together in the monastery should be such that it's neither restricted by the Vinaya or by the Bodhisattva precepts.

[11:06]

Nor have odds with the Vinaya or the Bodhisattva precepts. So he's supposed to have said that. And whether he said it or not, I think that sounds good to me. That we are not, that we do not become limited by or restricted by the regulations of personal purity. Nor do we at all, at least on all certain places, try not to go against them. But also the Bodhisattva precepts. That we would not be restricted by them. In other words, you could conceivably be restricted by regulations of personal purity. Can you imagine that? For example, one of them was that a male monk could not touch a woman.

[12:13]

Or could not be alone with a woman. Not to mention having such an intercourse with a woman, including with a woman. So that regulation might be restricted under some circumstances. Bodhisattva precepts, for example, or even not killing a precept which we shouldn't violate, still you might be working with a precept of not taking life in such a way that you are working with it in a way that restricted you. So Buddha, of course, practices not taking life. But the Buddha is not restricted by the precept of not taking life. The Buddha just doesn't take life. But it's not like some kind of like, oh jeez, God, I can't kill anybody in tradition.

[13:16]

It's not a restriction on Buddha. It's just natural. But even though it's not a restriction, Buddha doesn't care. So, we don't violate those personal purity precepts. We don't restrict it by them, according to the Dajang's instructions. And the same with the bodhisattva precepts. Even some nice precept of compassion, of course you shouldn't violate it if you're a bodhisattva. But it's possible that you'd be restricted by it. That your function would be restricted by them. However, if you look at either one of these types of precepts, and the commentary which explains how to practice them, you might get hung up. So, with these precepts, these monastic pure roses, I'm just going to encourage monks to find a way to practice

[14:19]

transcendence of the current contradiction between personal purity and compassion. And also, to transcend any kind of inattention to these wonderful precepts. Before getting stuck on them. Even in the early days of their practicing the Vinaya, there was a type of false view which was called Srila Paratha Paramarsa, which means, kind of like, basically, obsessively holding to the conventional understanding of the precepts. It was always, in the early days, Buddha presented the precepts, but then he would also say that there's a false view to hold to these too much. So what Bhajan is basically saying is, what, you could debate it that way, the importance of this is that basically,

[15:22]

you should do what's appropriate. And, in a given situation, of course, the Japanese, who was teaching at the L.A., and he had a monastery, and he had one precept over the doorway, which was basically to continue the process of transcendence. And how, of course, you have to get your umma, nirvana, who would ask, what was the Buddha doing during the whole during the whole career of the Buddha? And nirvana is the appropriate response. So the Buddha, and also, even in the early scriptures, the Buddha said that this Vinaya was not for the Buddha. The Buddha didn't violate this Vinaya, but the Buddha didn't follow it either. So the Buddha is not restricted by the regulations, and doesn't violate them.

[16:26]

The Buddha is not restricted by the precepts of compassion, and doesn't get violated by them. The Buddha does the appropriate thing. And these regulations were attempting to give monks a way to live appropriately. The emphasis here, that makes our behavior appropriate, is that the emphasis here is not on purifying self only, not on focusing on helping others, but on practically giving. Because practicing together is the way that's not restricted by the precepts, or by the rules. Of course, as you learn how to practice together,

[17:28]

in other words, as you learn the practice of practicing together, in other words, as you learn to be a Buddha, you probably do sometimes, become restricted by the regulations, or by them. Practicing together washes that out. So if you're stuck on the precepts, since you're not really supposed to be stuck on the precepts, because you're not really supposed to be doing the precepts by yourself, if you do the precepts by yourself, if you follow the regulations by yourself, you're stuck, or you're violating them. And your friends will bump into you, because you're either going against them, or you're holding still against them, and they're following you, and they run into you. You're going like this, you're carrying the precepts, and they're all just like following along, so they run into you.

[18:30]

Like that famous story of the two monks coming to the stream, and there's a woman standing there, and she's all dressed up, so she doesn't want to get in the way, and one of the monks just grabs her and carries her across, and then he puts her down, and they walk on, and then sometime later, the other monk who was carrying her says, you should not look, you're picking up women. That's against our tradition. You're violating our tradition. And he said, oh, you're still carrying her? I could have done that several more times. See, they're practicing together, so... even though you didn't go against the precepts, you kind of got stuck on them, because you were practicing together. You can see that. But really, it's not just the precepts,

[19:34]

but the way that they're working, the fact that they're walking together, brings up, made the opportunity for them to do the practice of the precepts together. It wasn't like doing one or the other thing, but doing the practice of the precepts. Because in practice, you do what one of them did, and what the other one didn't do. That's really the great practice. And these previous two kinds of practices, in some way, are really kind of like, easier to fall into, in some ways, a dualistic understanding. So we have them as a resource. And we have all these three types of resources. And this is part of this great opportunity we have. Now, work on these, during this practice period, but also be creative with these,

[20:36]

so that we can find guidelines or pure rules that will help us practice together. And we have at our disposal, as we practice together, these ancient forms, both the ancient Vinaya, the ancient Bodhisattva precepts, and as I'll mention a little bit more, the different versions of the Bodhisattva precepts, and we have the ancient Yajna Master regulations. We have all these that are at our disposal. And then we may apply the basic principles we all have here, to come up with new regulations that would help us even more practice together. Which I think is the wonderful spirit that finally was arrived at here. The great contribution of this level of precepts. Complete depiction. So again, all three types are good. All three are useful. And I kind of... Today, I feel that we need all three. The practice wouldn't be complete if we had any one of them alone.

[21:38]

And one more thing I want to say before I forget, and that is that the Soto Zen, and pretty much started in the time of Dogen, in the 13th century, doesn't use the 58 Bodhisattva precepts of the Brahmajyama Sutra. The Japanese founder of Soto Zen, Ehe Dogen Dai Risho, was trained as a monk in the Kendai tradition of Japan. It was transmitted in China. A very important school of Chinese Buddhism called Teng Tai. And they practiced with 58 Bodhisattva precepts. And Dogen, when he was 13, I believe, was ordained as a Kendai monk on Mount Hiei, which is the center of Kendai Buddhism in Japan. And he, I guess, received the 58 Bodhisattva precepts at that time. But when he started ordaining monks in his own temple,

[22:48]

I shouldn't say when he started, but in the end, that's when he died, he left behind manuals for transmitting not the 58, but just the first ten of the 58. And, in addition to that, the Refugees and the Pure Pure precepts. So, we set up a tradition of transmitting 16 Bodhisattva precepts, which is a unique characteristic of this particular school of Soto Zen. So, we have the 58 version, and we have the 16 version. And if you'd like a copy of the 16 Bodhisattva precepts of our school, you can just put a copy of them on the wall. This is my basic presentation. And what I look for, from now on, is that we practice together,

[23:53]

and that we practice together with the resources of the traditions of Buddhism. Not just the Mahayana, but also the individual Buddhist traditions. All the background traditions are good, there's respect, and that we become creative with them, because it is imperative that the school is to now come up with some new guidelines for how we can help each other practice together. Any comments? Yes. About together, like in the Vinaya tradition, the together form in purity, purity, and somebody... Say that again, there is a... Purity, hierarchy. Hierarchy, yes. And so, somebody, what somebody asks, that they kind of remind each other,

[24:54]

and that they are one, independent family. So there's a very strong value of being together. And now, in Buddhism, there's like everything, like reminding you, reminding everything, but it's very informal, like maybe ask that you have this spiritual relationship, and that you never found it, but otherwise, but it's very open, together, very open. And now in India, I'm wondering how is it together? Well, one of the oldest ceremonies in the Vinaya tradition is called Upasakha. And Upasakha means confession. Once a month, or twice a month, on the new moon and the full moon, monks in different geographical areas

[25:58]

would get together and recite the Vinaya, at least the regulation part of the Vinaya, together. It's a formal ceremony, which you mentioned. Right? They do that. And in the Shingi, there is a description of the ceremony, of how to do that Upasakha ceremony. So the Shingi presents, actually, a formal ceremony to celebrate usually the Bodhisattva precepts, that they usually celebrate. So there is a formal way, in the monastic regulations, of celebrating in each ceremony, except that they change the precepts that they celebrate. They don't celebrate the Vinaya precepts,

[27:01]

they celebrate the Bodhisattva precepts. And the regulations about how they get together and do that are the pure rules. The rules for personal purity are not describing how you do a group ceremony, although there were probably descriptions someplace about how to do that. That's not a personal purity practice. The Shingi would explain how we practice together. And the commentaries in the Shingi would elucidate how we can help each other practice together, practice the precepts together, practice the celebration of the precepts together, in a way where we don't violate the precepts and don't get stuck in them. So we don't violate the ceremonial procedures

[28:01]

and don't be restricted by them. And so we have that opportunity here at Zen Center all the time. When we do formal practice, we have the opportunity to relate. So, for example, if I'm working with a priest and the priest is wearing their robes, then I can go over to the priest and I can make adjustments on their robe. And as I make that adjustment, if the interaction of making the adjustment is neither restricting the relationship, nor violating it, then we have a moment of Buddha. A moment of where we're working with a form, but there's no restriction or inattention. It's balanced there. And it's both people doing it together, and both people feel, of course, very encouraged by this,

[29:03]

because this is basically what Buddha is. It's the appropriate adjustment of the robe. Sometimes the appropriate adjustment of the robe is not to adjust the robe. Sometimes when the monk comes and the robe's on, inside out or backwards or not even on, sometimes the appropriate thing to do is not say anything. But that still is practicing together. When the teacher sees a student who forgot her robe and doesn't say anything, sometimes that's the perfect and most appropriate way for them to be. Actually, I can say to one of the priests today, I said, What is the reason you're not wearing your robe? And she told me the reason why she wasn't wearing her robe. I said, Did you please wear your robe? I don't know if that was right or wrong. I mean, I shouldn't say right or wrong. I don't know if that was, like, practicing together. But anyway, she smiled and put her robe on.

[30:07]

I like it. That's a revelation that kind of comes forth in my mind. Like, there's only a teacher and a student. This can happen only between the teacher or some senior teacher can come forward and say the same thing, but not between, like, like priests and like that, or some people, not each other. What I'm talking about is the point of all this. It's not what we've already attained. So you haven't seen too much of the peers practicing together in this way. But ideally, that's when you get to that point where you could meet a peer and interact around a regulation in such a way that you find this perfect balance within the relationship. And even sometimes between so-called teacher

[31:14]

and so-called student, sometimes the teacher sees the student and maybe feels somewhat restricted by the regulation. In other words, they see the student maybe violating the regulation, but then they feel tense. They feel like they can't say anything. They feel like they can't make the suggestion to the student because they're restricted by the rule which they see as being violated. Or sometimes they say, oh, there's a student not according with the regulation. I think I'll go and make a suggestion. And they go do it, and the student feels very bad about this. Because although the teacher feels unrestricted, the student suddenly feels very restricted, like, you know, oppressed. So sometimes, you know, again, I might adjust someone's role, and they might feel, for some reason or other, like, you know, for example, maybe their mother used to, like, really give them a hard time about the way they wore their clothes. And suddenly, their mother comes back,

[32:16]

you know, when you adjust. And so they feel very restricted and unhappy. You know, and they didn't invite you to somehow reenact this childhood trauma. So then it seems not to work very well, even with the teacher and so-called teacher. The teacher, in that case, maybe doesn't feel so skillful. But sometimes, maybe that is skillful. Because sometimes that maybe that brings something up, and then a few minutes later, the student says, oh, that was my mother all of a sudden. Yeah, wow. So anyway, we're trying to find this, and it's not so easy to find it, but this is the game I'm talking about. This is called practicing together, and it's very challenging. But that's what Zen's about. It isn't just me being pure, or me being compassionate.

[33:17]

It's bringing the compassion into a relationship and seeing how it works. And the way it works sometimes is that people do not like your style of compassion. Or somebody else is giving you their style of compassion, and your compassion to their compassion is like, I don't want your compassion. And that maybe really is appropriate. But maybe it's not. So is it appropriate, or is it not? Sometimes we should stay away from people and leave them alone. Sometimes we shouldn't. Sometimes we don't. And then it's like, if you leave people alone, generally speaking, you don't have too much of a problem. Sometimes they feel bad if you don't leave them alone. But generally speaking, you stay away from people. You just find a nice little closet someplace and be fed under the door. You won't be like,

[34:19]

people will not call you a big troublemaker. But if you actually get outside and start relating to people, generally speaking, that's harder. But not necessarily always appropriate. However, if we're practicing together, those people who are out there interfering with our lives, we're practicing with them. We're practicing with the pushy, picky, interfering type of people. Don't you know those words? And there are some people like that, I've mentioned, right? We could have some in the cupboard. We got rid of them? So of course, of course she's just kidding. If she wasn't, we'd need to invite those people back. Or pay them to come back, didn't you? Yeah, pay them. But anyway, she's just kidding. We do have people like that here. And as a matter of fact, several are in the room. Sorry.

[35:22]

But I haven't run away from you yet. Interfering with my life. Pushing me around. Because of the teaching that we practice together, we don't go someplace where people leave us alone to practice. However, it's nice to find a way to be close and at the same time leave each other alone. To get really close and be very expressive and really leave everybody alone. While you're like driving them up the wall. Because we're practicing together, there isn't really anybody out there. That's really what it's about. There's not one or two people practicing. There's only one person practicing. And that's what's good. That person,

[36:29]

that one person can be very creative in their practice. Nothing to worry about. Yes? What you just said, we've got a good effect on our mind. There seems to be nothing else. Like again, the whole business thing kind of gets again like something. It needs to be worked out in our own mind. And so... No. It looks like... No. It doesn't get worked up only in your own mind. But it looks like a play, like a big play of evaluations and like meeting a lot of people and evaluating. It is a big play of evaluations because the people who are practicing together are evaluators. You're an evaluator. Your neighbor's an evaluator. Everybody's an evaluator. So practicing together is a play of evaluators. We're constantly evaluating each other.

[37:30]

You cannot avoid it. Like right now you're evaluating me. I'm coming. How do you... I don't know if I like you or not. No, that was pretty good. I'm not sure about... You're constantly evaluating me to see if I'm insulting you, agreeing with you, disagreeing with you, being brilliant, stupid, rude. You have a whole different set of dimensions, different categories under which you're judging me all the time. Plus you're judging all the other people who are not talking right now. You think it's fine if they're shutting up or they should be talking more. Why don't you people walk out? You have this incredible mind. You can do billions of calculations in a few seconds. And you're doing it. Other people are also doing it. And right now they're leaving you alone to some extent. But that's because their evaluations of you are such and such. If their evaluations were different, they'd come over to you and start doing things to you. We are evaluating. It's a play of evaluation. And it's a play of...

[38:30]

It's a play of judgment. It's a play of feeling. It's a play of thought. It's a play of sensation. It's a play of intuition. It's a play of understanding. It's a play of bodies and minds. It's incredibly... complex and dynamic. And that's what it is. It is in the play of all the people together doing all this stuff and enjoying how incredibly harmonious the situation is, actually, considering how complex it is. I saw this movie a few months ago called Monsoon Wedding. It's a picture of a street in India. It didn't look like an American street. There were lots of new cars driving down the street, but there were also rickshaws and lots of people on bicycles and lots of people walking and lots of people running and some people screaming and some people selling. It was very complex.

[39:31]

During the filming of that thing, which was just a few minutes, but during that film, it was all kind of working out. It was very intense. Generally speaking, the people looked happy. And there was plenty of suffering, too. There were poor people. There were cripples. A lot of the time, it does work out. It is possible. There are moments of harmony here and there. And if you add them all up, there's a tremendous, huge number of harmonious moments occurring in this world. But of course, a few moments of war are extremely difficult because it hurts so much and lasts so long. But there's also times when we get along. So like this morning, did you notice how well we got along this morning? It was difficult, though, wasn't it a little bit? Didn't you have some little bit of difficulty? Don't you love me? Wasn't that wonderful and difficult and harmonious this morning? So much was happening

[40:34]

in these two hours together. And lots of evaluation was going on. Did you notice? You were evaluating yourself. You were evaluating other people. We all were. We were all evaluating a lot of the other people. We weren't all evaluating everybody. I was the only one evaluating everybody. We couldn't see everybody. So you probably weren't evaluating people you couldn't see, except you might have thought, even some of you might have said, I don't know who else is over on that side of the room, but I think they're doing okay. People were probably evaluating the coffers. People were evaluating people's kidney. People were evaluating how many people left. Lots of evaluations going on. The people who are leaving are evaluating, the people who are staying are evaluating themselves. And they're evaluating the other people who are leaving with them who aren't quite as good

[41:35]

as them, don't have as good excuses. People are evaluating each other's bathroom practices. Did you notice? It was happening. Right here. Right here in the Zen monastery. And we got through it. Very nicely. And maybe, I don't know, maybe some people were like, I'm not violating the Vinaya precepts. I'm not restricted by them. I'm not violating the Bodhisattva precepts. I'm not restricted by them. That's really what it means to practice together. And it's not just we're all practicing together. That's true, we're practicing together, but how about these precepts? Oh, wow. And when you, it's not, it's not that you weren't practicing together, but you didn't appreciate how much you're practicing together until you look at these. They amplify the workings of the process.

[42:35]

There's certain regulations which make you consider things you wouldn't even think of. You know what I mean? There's certain regulations which, until you hear them, you don't even consider certain things. Like some people, until they hear about not lying, they never think of it. You have to be taught that, that that's a dimension of a harmonious relationship. And so on. So they aren't meant to cause us problems, they're meant to help us understand, actually, what harmony is. And what's the relationship between the evaluative mind and the precepts? What's the relationship? Yeah. Well, the precepts occur in the evaluative community. A person with the evaluative mind either hears about the precepts or doesn't. If they hear about them, then their evaluative mind interacts with the precepts and starts evaluating how they're doing with respect to the precepts

[43:37]

and perhaps how other people are doing with respect to the precepts, although that may not be asked for. But evaluative mind is non-stop. Every moment there's an evaluation. This is the omnipresent mental function. Is this pleasant? Is this unpleasant? Or I can't tell which. Do you like this? Maybe you like this or not like it. All these feelings and evaluations are normal part of the situation of living beings practicing together. Amoeba do it, too. They're evaluated, too. Like, is this food or poison? I cannot think of it. Nope. No more. All beings are evaluating situations. They evaluate and then they respond. Evaluate and respond. So let's be looking for the appropriate response to the appropriate response to what? To what? The appropriate response

[44:45]

to what arises but I mean it's response to what arises but what makes it appropriate? Appropriate means apropos of what? It's like whatever happens then whatever conditions arise that's what you're related to. But then what is the appropriate response? We always respond to what happens. But sometimes we don't see that our response is apropos of x, y, or z. So Buddhist in the Buddhist context when we say to the Buddha what's apropos then it means the Buddha has a response his response as to what happened were apropos of Buddha were apropos of who Buddha was and apropos of the Buddha's agenda. So we always do what's appropriate that means we always take into consideration

[45:46]

the situation but also appropriate to what? You get to decide appropriate to what apropos to what is important to you. I was thinking about shame and fear of blame and and fear of blame as their qualities of mind I consider them very helpful but how are they how are they not being restricted by what we would consider what generates the negative? Yes. But could decorum which you have more in common could that be not restricted? It can be restricted when you're meeting someone and and your sense of decorum makes you feel like you can't relate to them you feel you feel obstructed and hindered because of your sense of decorum like you'd like to

[46:47]

lick their cheek but you feel like that wouldn't be feckless you know you fear that you would be blamed for inappropriate saliva plantations so because of your sense of decorum you feel you might feel restricted but you might also feel like that actually that sense of that it wouldn't be that someone would blame you might guide you to instead of licking that person you might lick your chops instead and feel like yeah that was it so and that so your sense of decorum might guide you to do something you feel like that was just perfect you know just right on the mark and acropole means to the point on the mark so a sense of decorum sometimes helps you do you know

[47:47]

like a figure skater you know they sometimes what they're doing up there they're working with decorum moving in a way that seems really appropriate and that sense of decorum guides them in their physical movements so sometimes you feel like decorum supports you and guides you in beautiful movement and other times you feel like it's blocking you and so we look for like how can what's the way where where the where decorum or protocol in human relationships blocks it and where is that in that same situation is that same image of decorousness how can it be reimagined in such a way that you can work with it and it's not restricted and of course you can see how sometimes your sense of decorousness or decorum if you go against it you can see well that's violated so seeing how it can be violated and seeing how restricted it can be both so a sense of

[48:50]

but the sense of it the sense that there is a decorum and that it could be violated or it could block you that sense of those two sides that sense of it is what it means to work with decorum you have a sense of decorum if you have no sense of decorum then you have trouble finding this beautiful response because in every relationship in every moment of meeting any being that you're practicing together there is what is decorous it's there available but it's sometimes unless you're balanced in a way you sometimes have trouble realizing that together with the other person because they're you're worried about them blaming you so they have to become like taken into account here and that's part of what we're talking about and self-respect means sometimes you feel like you'd like to do something but because you feel like

[49:50]

you don't do it because you feel like it's kind of like beneath you so you have more respect for yourself and you put yourself in that situation so it's kind of like and that can be kind of like hinder you maybe from wearing Bermuda shorts so you feel like kind of restricted like I would like to wear Bermuda shorts but then maybe there's another way to wear them maybe not with tiger pattern or something maybe khaki would be okay you know you find a way that's appropriate you know like if you're I don't know what if you're a Buddhist priest or something you might think I shouldn't wear Bermuda shorts and maybe that's right but maybe there's a way to wear them that isn't restricted so both inwardly and outwardly these senses are actually

[50:50]

helpful dimensions to find the way to practice with all these precepts and find the appropriate response and yes the way in which you speak of the first few precepts is manners and observing the next precept and also the depth and the form are they always present in your situation? are they always present in your situation? I don't think so I'm not sure but the opposites define unwholesome situations so if you have the opposites

[51:51]

of them then you certainly have an unwholesome situation but I don't know if all wholesome situations have both of those in other words it might be possible to in a given moment of consciousness where the issue of self-respect is the dharma of self-respect and the dharma of decorousness or concern or being blamed by others that just isn't arising in your mind but you could have other factors such that you'd have a wholesome state but those two might those two I don't think those two are always in every wholesome state however if you have the opposite of them not just that they're not there but the opposite like in a certain moment of thought you might not be in the thought the consideration of self-respect might not be

[52:51]

in your mind can you imagine that? you know what I mean? like if you're doing a backflip there are certain phases of the backflip you might not be in the self-respect at all or decorum maybe at the beginning of the backflip you're not really in backflip but to have the opposite of them to not care to not respect yourself and to think I'm such a bum you know I could be cruel to this person and that would not be beneath me I'm a worthless creep and I don't care what people think of me I don't care if they don't like me I don't care if I cause trouble I don't care you know I don't give one blind

[53:51]

block that's the opposite and when that's present you have unwholeness but just because you have the absence of the other one or the presence of the other one the absence isn't enough to make it unwholesome it's the presence of the opposite that makes it unwholesome so those two are enough to guarantee unwholesomeness because those two are basically disregard the cause and effect which is more powerful than the wrong view of denying karmic causation but admitting karmic causation to be vividly aware of it then that goes with self-respect you know what's good for you really when you have self-respect you know this would be good and I'm a person that would be good for it and I'm a person who knows it's

[54:51]

good for me so that I may still do this stupid thing but it's stupid so people who know things are stupid still do stupid things but people who don't even know it's stupid and don't even think it's beneath them when they do it it's more damaging than definitely everything they do is on us I think that's the way it works but you're all welcome to check out your own psyche if you see it that way let me know and I'll change the book really good depending on what you said yes isn't it sometimes there's I don't care what they think well if what

[56:00]

you mean for example if what you mean is you're like I'm about to do something that really helps do it let's say I have a good I have a person I'm going to do this but I sense that somebody might not like it and I might say you know I don't really care that that person doesn't like it I mean for me I'm sorry for them that they don't like me doing this good thing I'm sorry for them but I don't care that they don't like me for doing it that kind of thing if you know I don't know what if the mother knows that it's going to be very painful to deliver her baby she might say you know I don't really care because I'm so much wanting to have this baby or a mother might be delivering a baby

[57:00]

And someone might say, I don't know what, maybe the mother's not married, and her father doesn't want her, thinks it's terrible that she's having a baby without being married. And she might say, you know, especially maybe when the baby's delivered, she might say, you know, we don't care if the father doesn't like her having a baby, we don't care if anybody doesn't like her having a baby. But I do care for them if they don't know how wonderful it is that this baby's here. Actually, I know a grandfather, personally, and I've heard of some fathers, who when their daughters have, or when their granddaughters have babies, and the granddaughter's not married, they don't, they feel angered in appreciating the baby. Even though they just got a grandchild, a gorgeous, unbelievably wonderful thing,

[58:03]

they can't appreciate it because the daughter didn't follow their idea of servitude. So I feel sorry for them, and not to care about them, not to feel sorry for them, that wouldn't be okay. But not to care that they don't like me, you know, for being the father, or blah blah, I don't mind for myself. That would be okay. That's what you meant, right? If something good happens, and you're happy, and someone's not happy, but you're happy that something good happened, it's okay to not care too much that they don't like you, or not happy with you. But you should feel sorry for them for not being, sort of, with it. Yes? I was wondering if it's not a foolish desire to be with you, to touch you,

[59:09]

and stuff like that, so I was wondering, I mean, like, if it's purely, purely a desire, then would you say that's pretty clear, like, Well, that's part of the dynamic here, is that the Vinaya teachings could promote a person, you might say, renouncing samsara. But still, even though they renounce samsara, and maybe they live together with some other people, who renounce samsara, that group of people renouncing samsara could be a resource for other people to hear Buddha's teachings, and in that sense, it could become quite a vehicle for compassion.

[60:12]

Because, although they renounce samsara, they renounce samsara with the body, so the body can be seen by other people. So the monastic life they live can be an encouragement to people. Even though those people may not yet be ready to go to monasteries themselves, they may still be involved in samsara, but still, these samsara dropouts could be an inspiration to people who are still in samsara. In that sense, they're very active in samsara. They're actively helping people in samsara. Even though they've renounced it. Now, on the other hand, if their renunciation is not really balanced, like a Buddha's renunciation, then their renunciation might not encourage people to practice Buddhism. They might see a bunch of monks who are practicing renunciation, but their renunciation is a little off. It's got a little holding in it.

[61:20]

And then, their renunciation, although it's pretty good in a way for them, in some ways, it actually might turn people away from Buddhism and say, well, those are renunciates, huh? Well, I'm never going to be interested in that. That renunciation is counting me out, rather than, I don't want to do that right now, but it's really cool that somebody is. And that's what a lot of people say about Zen Center, you know. I don't want to live at Zen Center, but I'm glad some people do. And I don't want to waste my time sitting all morning, but I'm glad somebody is doing that. I want to do this and that, but I'm glad somebody is just sitting there, witnessing silence. So, it could be that a monastic could discourage people, which is not the point of Buddha. Or they could encourage people.

[62:22]

They could encourage people by giving up what other people are interested in. They still encourage those people who are not interested in giving up still, but they're still interested in learning more about Buddhism before they're ready to practice renunciation. They're just starting to warm them up, hopefully. Now, the Zen school is supposed to be really good at this. At attracting people to practice by being somewhat of a renunciate, but in a way that really attracts people to renunciation. And so, part of being a renunciate is to, for example, do what's appropriate for certain people. And for certain people, what's appropriate is to make delicious meals, because they'll come for the good food, and then as they eat more and more of the good food, they'll get more and more interested in renunciation.

[63:22]

Everybody has to practice renunciation, but renunciation doesn't have to be practiced alone. Physically, if you practice renunciation alone, it's not Buddha's renunciation. Buddha's practice, all the dimensions of Buddha's practice, are practiced together. So if we practice renunciation at a Zen center, we should practice it in a way that people find it lovely. However, if they don't find it lovely, rather than not care about it, we more like use their input as guidance to, what do you call it, to refine our product in such a way that does encourage them, without using that as an excuse to not practice renunciation. And that's why we're practicing together. Part of renunciation is to give up your style of renunciation.

[64:25]

But not giving up so much that you actually just simply are not renouncing anything. Yes? Can you suggest a big expression of renunciation that people have? I wasn't so much thinking of necessarily a new expression coming out of the 16 Bodhisattva Precepts, but because we have the 16 Bodhisattva Precepts, that's part of our practice. But we also have the Vinaya to be aware of. But the way we work with the 16 Bodhisattva Precepts, that is part of the creative process. So for example, the way we do the ceremony, of course it's in English, that's one of the ways we've changed it. Hoping that there would be more,

[65:27]

I guess hoping that there would be more encouraging people to use Japanese. Like they changed the math and Catholicism from Latin to English, and some people didn't agree with that. But we haven't had that much negative feedback from switching the ordination ceremonies from Japanese to English. That's one change. Another change is, not so much in terms of the Bodhisattva Precepts, but more in terms of the procedures and the regulations, is that the way women are interacting with the Precepts is more equal and coherent than it was in Asia. That's one change over on this side. There's no Bodhisattva Precept that says men and women shouldn't practice it. There's very few monasteries in China and Japan and Korea where men and women are practicing together.

[66:28]

So that's one of the changes. And we haven't even made a rule that says men and women can practice together. We haven't made that regulation. But in fact, it's there. Maybe we should actually say it. That would be a new regulation. Men and women can practice together in a monastery. I don't know. The way that the 16 Bodhisattva Precepts were translated, as mentioned a little while ago, was that the Three Pure Precepts can be translated as something like, I vow to refrain from all evil actions. I vow to do all good and I vow to say all good things. But that's not actually the first point.

[67:32]

It's not actually what it says in the Chinese or Japanese. What it actually says is, I vow to embrace and sustain regulations and ceremonies. In other words, the ceremony for receiving the Bodhisattva Precepts as it's presented in the Shingon is that the first Pure Precept is to practice the Shingon. But for various reasons, it didn't say it that way. And I think the reason it's not saying it that way, I guess it's not saying it that way, is because people feel a little uneasy about regulations and ceremonies. But in fact, I personally have put it back in in my presentation of those Precepts because that's actually what it says. And I think it's very good for us now, as we take Bodhisattva Precepts, to vow to practice regulations and ceremonies. Which takes us to Zen and takes us to recognizing that

[68:35]

part of the way you help people is with ceremonies and regulations. It isn't just by avoiding evil. Of course that's good, and we want to do that. But our way of avoiding evil is more like we're giving people something to work with and we avoid evil by learning how to practice together rather than personally trying to avoid evil. So the rendition of the Precepts which we're using at Zen Center were actually more of the personal purity type of presentation. And it's actually using the way that the Dharmapada presents the Precepts. Avoid evil, practice good, and clarify your mind. In our real sutra, it does actually say in the Japanese original avoid evil, practice good, and stay at peace. That's what it says in the Japanese original. But in the Precept of Transmission Ceremony it says embrace and sustain the regulations and ceremonies.

[69:36]

So switching back actually in that case was a case where I feel myself, and I don't know how this is going to be treated because it's something we'll start talking about that the watering it down from, well not watering it down actually but to say it that way to avoid this regulation and ceremonies I feel was a step backwards. And now I can step forward and go back to what was embraced and now deal with that. I think also a part of what has been created with the Shingi is to teach people about them. And to invite people to think of ways that our regulations and ceremonies could not violate the early individual purification practices and not the restricted

[70:36]

and not violate for the restricted other philosophical steps. What regulations and ceremonies because these have regulations and ceremonies but they're for a different environment. This is saying in our present situation what regulations and ceremonies inspire and encourage the practice. They won't be the same. So, looking at these kinds of things in accord with the Vinaya in a way it doesn't violate the Vinaya and also looking at these things isn't being restricted by the Vinaya because we're encouraged by the Vinaya to not be restricted by the Vinaya to say we can't make up new rules they have to be like the way practiced in India. So we keep looking over at India and thinking of how that was good then and what were the advantages for animals and disadvantages for animals. For example, what are the disadvantages of treating them differently? Why are we treating them differently?

[71:37]

What if we study that at the same time we don't ignore the little mistakes let's find out how do they apply today that's what these are and can we think of anything new? So, for example, we have Kauravyoki we also have changed that somewhat the Japanese way of doing it which has lots of virtues the way they do it most often in monasteries is when they're serving seconds people stop eating so you have a limited amount of time and then if you stop eating during seconds unless everybody would take longer to finish their seconds but some people do not take seconds so then if everybody stops some people have less time to eat so some people are not going to get enough and for some people that will drive them out of the monastery

[72:44]

so at the end of the day we've made a compromise of letting people continue to eat what they've already received at first last seconds of their service we've changed that because we thought it was more appropriate having a certain discussion about it because it's so lovely and ungreedy to actually stop but the disadvantage of that is that some people stop eating can't eat during seconds they can't finish what they got on first during seconds because they won't be able to get seconds or they won't be able to finish their seconds because other people, almost everybody because we don't wait everybody is completely done before we bring in the water and if you're the last person to be eating even if you're the last you've got a big bowl of brown rice and everybody else in the room is finished and you've got this bowl of brown rice that you're going to chew each bite 50 times

[73:47]

you feel bad keeping them waiting because some of them are sitting below you and they would like to take their break and the servers are all lined up like so you feel like, well either you've got to gobble the food which isn't good for your health or the next time you're not going to get as much we've made that change because there's just a little bit more time and other changes we can make more dramatic and whatnot although even that change has been discussed and argued about for quite a while how much of this changing is standard form? is there a place, is it an agent's changing that we would remove and drop them

[74:49]

or are we reducing standard changing? just like those that we do see from Yoshi's temple? how is our changing? there are more than one there supposedly was a Takujo shingri by John Waihai supposedly made a shingri but we don't have it anymore there is one but it's considered to be not authentic at the time that Dogen Zenji went to China he went to China in 1225 when he went there the most influential shingri there was more than one but the most influential shingri was called the Zen Garden Churus Changyang Jingui which was edited because it was put together with lots of other shingris which existed before was edited in 1103 about 120 years before Dogen went there that text, that Chinese text

[75:52]

was the text that basically was the basis for Dogen's shingri we have a text that you know called Eihei Shingri we have that and that's based really much on this Chinese text called Changyang Jingui we have those two those are shingris those are guidelines but the point of those guidelines is still if you read those guidelines and still try to find out what's appropriate today so for example they have in their rules about how to do Zazen there's a Zazen section it's called it's called Zazen Zazen Yi Zazen Yi which means a ceremony for Zazen it's in that text, the Chinese text and Dogen's early versions it's called Zazen Yi I mean that's the Japanese way

[76:53]

the Chinese way of saying it is Zazen Yi Dogen wrote a Zazen Yi also he wrote Fukan Zazen Yi and it's an early version of Fukan Zazen Yi very much like the one in this shingri so the shingri has a Zazen Yi in it the subkozen, early subkozen pretty much copy verbatim not completely verbatim different parts of verbatim from that text however that Zazen Yi is not always appropriate to practice and Fukan Zazen Yi even is not always appropriate to practice Fukan Zazen Yi is universal, a general encouragement to the ceremony of Zazen which means this works for most people most of the time but it's not always appropriate to follow those instructions none of these shingri

[77:54]

should be followed all the time the way you literally read it that's the basic shingri and we do have these shingri there's other shingri about how to wear the robe for example and how to enter the zendo how to do Ijin how to get on the tan how to cross your legs how to wear your robes how to shave your head and we do we have some tradition about how to do all these things however the abbess of Zen Center just told me that she went to do an ordination and the other abbess the way she taught her students to work with the robe was really surprising to her so within Zen Center people are doing certain ceremonies differently but that's part of practicing different teachers will teach different things and also your teacher will teach you in ways you don't like and so on so

[78:55]

how to wear your robes how to clean your bowls how to eat with your bowls how to wash your face how to get in bed how to get out of bed these are shingri and in the as you know in hei shingri and and zen an shingri the Chinese and Japanese shingri of our tradition have rules about how to do most of the activities of their life but still these are basically just kindness offered by the ancestors for us to figure out how to live today together so like someone said to me after lunch today could we change the procedures about how and when to use gomashio so there was a a shingri written about the use of gomashio and I said yeah

[79:56]

and this person was very happy we were practicing together in that way yeah yeah like shoho was talking about hierarchy and there's rules in the shingri about how to relate to people who are higher than you in hierarchy however what I'm emphasizing here which was not emphasized so much here when I say here I mean in the shingri was not emphasized so much in early buddhism early buddhism gave regulations about how to relate to seniors too for example it taught females all females even a female that had been practicing for 50 years was lower status

[80:58]

than a beginning male monk so we changed that here we have a different arrangement here female monks who have been practicing 20 years are senior to male monks who have been practicing 1 they are junior to that person and there are Japanese and Chinese shingri which tell you how to relate to seniors however we have not yet fully I would say we have not yet fully mined those teachings in other words people in the zen center this zen center are not yet not yet familiar with the shingri about how to relate to a senior and so part of what I would recommend in order to be creative is that you read the shingri for example about how to relate to a senior and then discuss with someone like me about how disgusting it is

[81:58]

to talk about shingri you know because you are supposed to really pay intense respect for these seniors which we don't see too much around this place for good reason these people are like they have been practicing 20 years and they are like that? I'm supposed to respect them? yeah according to the shingri of course but maybe that's not appropriate maybe years of practice don't really count here because it doesn't really affect these people so I respect them but I tell you it does affect them you should have seen them before so you know this person actually is like not as well developed as you are but they've been around longer but what you are respecting is not how great they are but how far they've come you respect that they've been practicing 20 years

[82:58]

you've only been practicing you're better than them I agree you've only been practicing one year so you've only come along one year so we're respecting the 20 years of practice not how good this person is how are we going to work that out? how is that going to be appropriate? this is part of our creative work would be to look at that particular fascicle which we're not practicing yet about how to relate to a senior which is in their early opinion but do it in a creative way say well I've read this and I don't really have I have trouble with it what wouldn't you have trouble with? what could you express? how would you respect a senior? let's talk about that that's part of our work because it is it's a potentially rich area because seniority doesn't mean something why does it mean something? what makes it mean something? what makes me think it means something? well because I look at the ancient Buddhist tradition it means something to me so I think

[83:59]

maybe we should look at that but how can we practice with seniority in a way that doesn't skip up we're already practicing pretty well in a way of violating seniority we're pretty good at that in other words we're fairly good at disrespecting people we got that down good work you know what I mean? do you? you don't seem to do what I'm talking about you're not kind of laughing or nodding your head I see people not very respectful of senior people I see them afraid of senior people I see people in positions of power but I don't see much respect for senior people it's culture yes it's culture it's part of it's part of you know the wild west but anyway I understand but let's look at that let's let's talk about it that's part of being a creator

[85:00]

could we possibly find a way to not violate this ancient tradition which means you're supposed to respect priests you're supposed to respect seniors you're supposed to mean that the Buddha recommended it in some way so we can work with this and not that it seems apropos of world peace Buddha's Buddha's into world peace that's what they're really about right these precepts are supposed to promote it we're overlooking some just because they're so obnoxious just look at them overlooking them and not looking at them is violating them you understand not respecting them and studying them is kind of violating them if we study them then we we'll quickly start to be restricted by them if you read these instructions you're going blah blah it won't be a problem if you took them literally but what can we find what would be the appropriate way to deal with the fact that we have different viewpoints of experience this is I invite you to look at this and bring this forward

[86:01]

from now on wherever you practice wherever you practice Zen or any other form of Buddhism deal with a fact the historical fact that seniority is an issue not skill is an issue too of course somebody who's really brilliant and clever and energetic of course they people give them a lot to do they become the director they become the chairperson but Buddhism also says some of you some some kind of dumb not very energetic kind of wimpy and vulnerable person has been practicing for 50 years as an object of admiration you bow to him a young monk a green shark bows to some old woman but we should look at him more and then there's and then there's other things too which we have some forgiveness about

[87:03]

like for example washing our face in a certain way in a certain chance there's rituals that you could do I encourage us to look at that because those are the ways that we look at them together those are the ways to transcend the what do you call it the the contradiction between compassion and personal kindness

[87:29]

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ