You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Mindful Presence Through Cosmic Mudra

The talk emphasizes the practice of presence through a yogic mudra, advocating moment-to-moment awareness and the effort required to maintain it. This presence is linked to meeting people with attentiveness and receptivity. The approach involves balancing alertness and relaxation, while the engagement with the mudra serves both as a meditative practice and a metaphor for interaction, encouraging patience and understanding in relationships.

- Referenced Yogic Mudra: Cosmic Concentration Mudra (Dharmachakra Mudra)

-

This mudra serves as a tool for cultivating concentration, presence, and grounding. It demands continuous effort to maintain proper posture, which parallels the effort needed to be fully present in interactions with others.

-

Buddhist Teachings on Patience and Compassion

- References to the Buddha's teachings on patience, including the practice of love and non-violence even when confronted with aggression, highlight the importance of developing patience as an essential spiritual practice. These teachings emphasize overcoming natural reactive tendencies through dedicated practice.

AI Suggested Title: Mindful Presence Through Cosmic Mudra

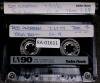

Side:

A:

Speaker: Reb Anderson

Location: The Yoga Room

Possible Title: CL 1

Additional Text: Tape 2

B:

Speaker: Reb Anderson

Location: The Yoga Room

Possible Title: CL 4

Additional Text: Tape 2

@AI-Vision_v003

Every time you cross your legs, you mean? Every time I cross my legs, yeah. A lot of people have the experience of their legs falling asleep when they cross their legs, sometimes for years. I haven't run into any problem with that unless when you uncross them, the numbness stays for 10 minutes or 15 minutes or longer, and I think you have a problem. But as long as when you uncross them, you experience the feeling coming back, I haven't experienced people having any damage from that. You have to be careful, though, not to stand up before the feet wake up. So if your feet are asleep, you can just stay at your seat until they wake up, uncross them. But I haven't seen a problem of that kind of sleepiness that comes back right away. And it's pretty common. I see some other people slow to get up, waking their legs up.

[01:03]

Sometimes it stays for a long time, and sometimes... It just stays, you know, you just get it at the beginning and it goes away. But some people, after many years still, sometimes their legs fall asleep. Yes. I've had that for probably 15 years. My right leg falls asleep. Yeah. And I bear it as much as I can now until it starts burning. Uh-huh. Yeah, you can adjust your posture if you feel it's getting too uncomfortable. But I'm just saying I haven't found it to be damaging. But the other kind of numbness that lasts for 10 minutes, 15 minutes, half an hour or longer, that kind probably you should let me know. Probably you change your posture or stop sitting until we find a way to do it so it doesn't happen. I was talking to someone, and I can't remember exactly her question, but it was something like, how should I meet each person, or how should I meet each situation?

[02:25]

And while I was talking to her, my hands were in this this yogic posture, this yogic mudra called the concentration, the cosmic concentration mudra. Mudra means seal or ring. And I just thought, well, the way to meet every situation is like, is the way we hold this mudra. That's the way to meet each situation. I feel that for me, making this mudra, making this oval with my hand, when I do this, I feel like it's kind of the way I like to meet people. It's kind of like the way I want to meet my own experience. So what's going on with this mudra is, for one thing,

[03:26]

It includes making this shape and it makes... No, Razi, no. No. Making this shape, this oval with my hands, but also it... The hardest part of the mudra for me is keeping my small fingers, my baby fingers, in contact with my abdomen. That's the hardest part for me. And... It's almost like an every moment effort I have to make to keep my fingers touching my abdomen because they don't rest there. I guess if I had a different shaped stomach, like if I had a nice big round stomach, I could just set my hands on my stomach and they would just rest there. But actually I have to make an effort every moment to bring my hands in contact with my abdomen. So that particular point of contact between the outside of my baby fingers and my abdomen makes me pay attention each moment and be there at this point of contact each moment, just about each moment.

[04:43]

If I lose it for a moment, my hands tend to move away, move down or away from my abdomen. So the first point is that I actually have to be right there with that each moment. And that's the way I want to be when I meet a person, because I want to be there not just at the beginning of the conversation and not just at the end and not just in the middle, but each moment to be there. And with my body, too. I want to be with my body. I'd like to be with my body each moment. And when my hand is touching my abdomen, I am with my body each moment it touches. I have to be there. So that this mudra, this yoga practice of touching my hand and my abdomen is one that

[05:46]

really test my presence. I feel, generally speaking, I feel pretty present. I do. Which I, I mean, I feel good about that. But, I can feel pretty present and still not, and still not like be able to, or willing to just touch my fingers to my abdomen. Now, why not? Do I have something better to do like when I'm meditating? Why not? Why, you know, Why not do that? Well, there's really not a good excuse, but it's easy not to. It's easy for my hands to slip down like this. Then I don't have to make that effort. But I really don't... I really don't put it... I really don't not want to make the effort. I do want to make the effort, but I can't say I really do want to make the effort because sometimes I don't. Sometimes I do let them slide, so to say that I want to means... That's my basic policy.

[06:49]

And I think that's a good idea. But in fact, I sometimes are down here just because I want to like, just kind of like, be lazy. You know, just kind of like, maybe not slouch over, maybe still sit up straight, but not make the total effort of bringing my hands in touch with my abdomen. So I'm a little bit lazy. A little bit kind of like, oh, it's kind of nice just to sit here. Yeah. I'm not really asleep, but it's very restful. But to bring my hands about three inches back and touch my abdomen, it's not so sleepy. But that's the way to meet people, is to be right there. So this exercise of holding your mudra against your abdomen is a way to get used to the kind of effort that probably you do want to bring to each meeting with each person and with each experience.

[07:59]

Now, not only that, not only does that kind of presence, presence, presence, presence need to be there in order to hold the mudra in the proper position, But to make the mudra also involves, you have to pay attention to make the shape too. The positioning takes constant attention, but also to make the shape. The fingers, some people can be fairly sleepy. I can be fairly sleepy and keep the thumbs together. If I let my hands slide down away from my body, I can sort of keep my hands, my thumbs together. it's possible. But for a lot of people, the thumbs do fall apart when they get sleepy. So keeping them together, there's an element of alertness there. For me, it doesn't require as much attention and as much effort to keep the thumbs together as it does to keep the thumbs together and touch the abdomen.

[09:09]

But another thing about this, keeping the mudra this way, especially if you keep the top of the mudra somewhat flat, and especially if you keep your knuckles unbent, is that you have to be somewhat relaxed too to make it. So making the mudra, right now I'm making this hand mudra the way I have it for myself. I feel right now in my hand, I feel alertness and presence there. And I also feel relaxed and not tense. One problem with this mudra for people that have long fingernails is it's hard to touch the tips of the thumbs if you have long fingernails. So it's probably good to get those portable fingernails. that you can put on for when you're out and about and take them off for meditation. Do you have those? You go, stick on, stick on.

[10:12]

Removable, whatever. Attachable and detachable. Because if you have long fingernails, then you kind of have to, your fingernails have, your fingers kind of have to point up a little bit in order to touch them. Right? And this particular position is a little bit more tense when the fingers are making kind of a peak or a mountain. It's a little more tense than this one. When I... Actually, in my early years of practice at Zen Center, one time I went out to dinner with one of my fellow students, and he said to me, He said, do you know what that clicking sound that's happening during meditation is? I said, no. And then he started to show me what the clicking sound was, and I realized that the clicking sound he was referring to was the sound of me snapping my fingernails, my thumbnails, like this, back and forth.

[11:25]

I wasn't twiddling my thumbs, but I was going like this. I didn't really notice it until he asked me about that. He often sat next to me. And I think he really didn't know what it was, but he wondered what that sound was. I thought maybe I would know since I was right near him. And I said, oh, I know what it is. And I stopped. Also, this hand mudra requires not only to keep it in this position, requires this constant effort and balance between alertness and relaxation. But I also have to coordinate other parts of my body in order to have it there in a way that's not a strain, which is kind of difficult to coordinate all those different parts, which also takes a lot of effort. So in order to do this mudra,

[12:28]

There has to be, for me, has to be quite a bit of enthusiasm or, you know, real energy to make the effort to do it. Having the hands on the knees, like some of you meditate with your hands on your knees and a lot of other people do it. It's, you know, it's okay. But it doesn't offer you this kind of way to like, some people can have their hands on their knees and like really be present, I'm sure. I probably could too. Okay? Maybe I could be present with my hands on my knees while I'm sitting cross-legged. But since I have such a hard time keeping my hands in touch with my abdomen, Maybe when I have my, because it's hard for me to be that present, maybe when I have my hands on my knees, I'm not being that present, but there's nothing in my, there's nothing in this mudra that tells me if I'm not being present.

[13:33]

Because they can sit here and I can be completely asleep with my hands on my knees. Matter of fact, When I used to work outside Zen Center and come back to Zen Center for meditation, I used to live there and I worked outside, I would actually go into my room before evening meditation after work and sit cross-legged with my hands on my knees and go to sleep. Because I could go to sleep very fast in that posture. It was very relaxing for me. But I would intentionally sit in this posture as a sleeping posture. So I'm not saying that everybody who sits this way is sleeping, but for me, I can sit this way and sleep, but I can't sit this way, I can't sit with my hand touching my abdomen and go to sleep. It doesn't stay there. Even I can be awake and it won't stay there unless I'm making that effort. So, some people are so alert that they don't even need this posture, which ultimately that's what we want is to be

[14:40]

is to be able to be really present and not just dreaming that we're present, even though we don't necessarily have our hand in this mudra. And in fact, it's hard to walk around unless you have like a, you know, a big shawl around you. It's hard to walk around with your hands in this mudra. But this kind of presence, I think, if you meet each person with, if you're willing to make this effort to hold your hands here, then maybe you'd be willing to make the effort to really be there with the person you're meeting. Another thing about this mudra is that your hands are in kind of a receptive posture, so it's like... it's like a listening posture. So you're present and receptive. You're not... You're putting your presence out there, you're putting your readiness out there, but you're also receiving and receptive. So, there's also patience involved here because, for me, sitting here for half an hour like we just did, I was able to, you know, I did pretty well with my mudra.

[15:52]

I was happy with being able to do it for 30 minutes, but how about doing it many periods a day for a week, you know, am I going to like be present like in that way for period after period for a week? It's not easy. It takes patience and it takes enthusiasm. You have to really be enthusiastic to do that. And some people do it the whole week and I would say they could understand that they're being quite enthusiastic. So congratulations to someone who does that. But again, when you meet somebody, don't you want to be enthusiastic? Don't you want to really like bring your energy to the meeting? Yes, Martin? What practices would you suggest to help us be more present when we're not meditating? Like just during the day interacting with other people or being by yourself?

[16:54]

Well, part of what I'm suggesting now is the yoga practice of this mudra And when you get a feeling, when you can do this mudra, if you can't do this mudra, then I would say, how would you possibly be able to practice with people in a more complicated situation? This is hard for me to do this, actually. But it's a lot easier because I've got something to check myself. How do I know when I'm talking to somebody in the supermarket whether my hands are on my knees or touching my abdomen? In other words, whether I have the kind of presence that's required to keep those fingers in contact with my abdomen or whether I'm in the kind of presence where I have my hands on my knees and I'm half asleep. So you like to take that step, but I like to say, first of all, let's talk about this thing. If you can do this, it will

[17:55]

spread if you can stand to make this to devote your attentions to keeping your fingers in in contact with the abdomen not partly because right now this is a way for you to be with yourself and right now this is a way for you to be with the other people in the room and right now this is a way for you to encourage them to be present with you and to be present with themselves right now it is If you can do it now, it will spread. If you can't do it now, learn to do it now. Learn to do it in this situation. Now we can talk about how to spread it, but before we talk about that, let's talk about doing it now. In this situation, this structured situation where you get this feedback, where not only can you check yourself, but someone else can check you. Okay? So let's wait for a second before we go on to that. Mary?

[18:57]

Mary? right I do too from and for for a number of years trying to do this mudra I got pain under my or particularly under my left shoulder blade and it didn't happen during the regular daily sittings, but during the longer sittings, where there's many periods a day, then it would come. And I had it for two and a half years, I had that. And then my body found its place, and that was that. But if I... So basically, it's pretty much trial and error. You know, like, I didn't ask you, but is it all right if I adjust your posture when you're sitting? So I can come around in the next period of meditation and adjust your posture, but even if I adjust your posture, the slightest, there might be a slight, a slight thing about the way you're holding yourself, a slight difference in the way you hold your arms, which would cause tension in your shoulders, like, is this the trapezius?

[20:19]

Up here. People get tension in the trapezius and also in the muscles under the, particularly under, I think, under the, what do you call them? Huh? Shoulder blades. Yeah. Those are common places to get pain from trying to hold this mudra. And I would say if you start getting tension in your trapezius or neck or upper back, wherever, from doing this, it's okay to rest. But sometimes, even when it's not painful, I'm tempted to rest. But I used to have a lot of pain from this, so in that time then I would rest. I would put my hands down lower to let my lap hold some of the weight, or put my hands on my knees. But after I felt relaxed, I'd go back. There's some way, there's some combination of the way of holding your shoulders and neck and back and chest, there's some way that's probably not very far away, because you're not, you know, your posture's pretty close to where you want it to be, where it'll all just fall into place.

[21:29]

The problem is, even when you get in that spot, sometimes you don't know it right away, because you're still a little sore from being out of the position before. So even though you move into it, you can't be sure. So it's, sometimes you have to try the experiment for, if you're trying a new position, to try it long enough to give it a chance. Sometimes you're in a position and you relax, but you're still sore from the tension from before. But if you put enough time in, the discomfort will guide you to the right posture. But you don't want to get too uncomfortable because you can go into spasm and so on. So a little discomfort is guiding you to find that proper adjustment. A lot of discomfort may be too much, and you should probably rest. You have to learn which is which. But I had a lot of problems, like I said, for quite a long time, and then finally I found it. And once I found it, then that was it. But I had been practicing for about three years when I had this problem.

[22:37]

From maybe about like two years to four and a half years, I had that problem. And then I didn't have it after that. But still, if I don't... Well, I'll put it this way. Still, sometimes when I'm sitting, I have pain. And usually when I have pain, it's because my posture is off. And I usually know what to do. Not always, but... It's usually some kind of laziness on my part that's causing my pain, usually, not always. There's certain, I mean, particularly pain in the neck, shoulders, and back. So it's trial and error. And I can adjust your posture, but that can give you an idea approximately of where I think is your balanced posture. But still, you might have the problem. Did you have your hand raised, Terry?

[23:43]

Yeah. Regarding the feet, I mean legs, I know that there are a lot of different ways of putting one's legs, and I work toward something like a lotus. I wonder if you could talk about the values of training the body toward a lotus and how one does that. Okay, well, first of all, I just want to say that this mudra, you don't need to sit in full lotus or half lotus to do this mudra because, although when I do it, I place my hand on the heel of my upper leg. That's actually the place I put it. But you're not leaning on that foot, so even if the foot's not there, you can still do this mudra, okay? So half lotus and full lotus have...

[24:45]

have the virtue, particularly full nose has the virtue of once you're sitting in it properly, it's very stimulating. And stimulating means, I would say not stimulating so much, but energizing. And also your body feels very secure and stable when you're in the posture. So it has that advantage of being very stable and making your body feel very secure and energized, it also makes it easier to keep your back upright when you're sitting in full lotus or half lotus. How to work towards it? I will try to... There's a number of exercises you can do. Have you seen them? I'll bring an article next time. How many people would like a copy of that article? 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18.

[25:54]

Okay. So I'll bring copies of that article which has a bunch of exercises that are helpful in general, but particularly helpful to prepare you to sit cross-legged. Yes. Noticing that when I try and find that upright position at first, I can really sense it, feel it. Yes. And after a while of sitting, I find that I start to lean without noticing. Yes. But I'm leaning away. Yes. And you do finally notice it after a while? Yes. I'm wondering what's... I don't know. What is that? I don't know. I'm not sure what the conditions for it would be. But I would just say that, you know, there you've got that problem and when you notice it, you know, come back to what you think is proper and maybe check some... Again, this...

[27:09]

Holding this mudra does not necessarily mean that you won't be leaning backwards, but keeping your hand in contact with your abdomen I think does. Does that really help you from leaning backwards? Not necessarily. It might be easier to hold it there if you're leaning backwards. I should try that. Anyway, I'll keep an eye on you. You can also, you can like, sometimes maybe, if you can, sit with a, you know, a three-way mirror sometime and sit there and then just, you know, don't look at it, but then occasionally look and see if you can catch the time when you start leaning backwards.

[28:21]

If you can set up a three-way mirror, sometimes that helps. Yes. Marcia. The stabilizing you talked about last week, man, using the mudra, if I understand... I don't understand stabilizing, I guess. If you use the mudra, is your intention, man, to stabilize yourself by being for yourself so that you are ready to start meditation, or... And with meditation. For me, and I think for anybody, in my opinion about them anyway, if you're sitting on the earth upright and you're making this mudra with your hands and your fingers are balanced this way and you're touching your abdomen, you're meditating. Okay? This isn't a preparation for meditation. It's meditation. So, does that make sense?

[29:26]

Yes. So do you have a question about that? Last week you said stabilizing is before insight. And I guess I don't understand stabilizing then. Well, this kind of postural attention is stabilizing. It's a stabilizing type of meditation. And it involves... giving you have to be careful about you know how you position your body you have to be patient there's patience there there's enthusiasm and there's concentration so they're all there in creating this posture and this posture in itself is already a stabilization posture okay so is your question now what about insight is that your question So this is a stabilizing practice.

[30:28]

It's stabilizing. It's calming. It's present, but it's not a sleepy calming. It's not dull. You have to be fairly sharp to do this. So it balances alertness and relaxation, gentleness and effort. presence, but the presence can't be too intense, otherwise you won't be able to keep it up. If you try too hard, if you push too hard against your abdomen to keep it there, like if you push really hard, then you'd really be aware if you stopped, right? But you can't keep that up. So you've got to make an effort that's enjoyable in a way. and not too much so you can sustain it. So all these things are involved in balancing and stabilizing and a tranquility that's not sleepy.

[31:37]

Okay? Yes. Nancy. I find the course really difficult from the point of view that any patients that I had when I came here, I feel like I became way more impatient after the class. And any kind of dissatisfaction that was low level is... high level now. If I felt like I was a giving person before, now I feel like I don't want to give. And I feel like this happens to me whenever I take a course like this. It's like all my resistance or even what you were saying about effort. I notice at work I don't want to make any effort. I don't want to do my job. Whereas I feel I was doing my job before the class started.

[32:45]

Now I loudly don't want to do my job. And so it is difficult to be in the course. I just wanted to say that in detail. It's difficult to be in the course? Or is it difficult? It makes everything in your life worse. It's not just in the course, but when you leave the room, everything's more difficult. Right. I'm more impatient. If I can use what you're saying as we go, and I do, I can calm myself down. But, like, the days right after the class, it's real loud. And it does get better as the week goes by. Because I remember what you said. I try to use what you're saying. And when you try to use it, and then what happens? Well, I don't know how to put this exactly, but well, first of all, I'd say that this is normal, just what you're describing.

[34:12]

A lot of people are in this world and they do not feel particularly lazy, resistant, stingy, or impatient. They don't feel that way. I mean, they have their cares and woes, but they don't think of themselves necessarily as on top of all my other problems, I've got these problems that I just mentioned. And some people think that they're impatient. But most impatient people, I shouldn't say I don't know most, but a lot of impatient people are too impatient to notice that they're impatient. You have to be somewhat patient to notice that you're impatient. If you're really angry, you don't, like, notice that you're impatient. You just, you know, you're just angry. There's a lot of people tell me they're angry, and I say, well, what about patience?

[35:19]

What do you mean, what about patience? It's just not an issue, you know? They don't even think of it. And they go to a class, and somebody says, patience, they say, patience, well, you know, I heard that in grade school, but, you know, give me a break. Patience? Usually, if people are angry, usually something's bothering them. Usually they have some pain. But they often don't even notice it. They just immediately, pain, anger. There's no like pain, trying to practice patience, slipping and then practicing anger. It just, they don't even consider patience. And they weren't practicing patience when the pain hit. So, everybody practices patience. Some, because everybody's not enraged 24 hours a day. But you're irritated almost 24 hours a day. There's something bothering you most of the time, even if something pleasant is happening. So you come into a room like this, somebody brings up patients, and then you get the chance to look at the fact of your patient's practice.

[36:29]

But almost nobody's patient's practice is not in need of development. But, again, most people don't. Even think about patience. I mean, even Zen students who are like living in Zen center, practice for a long time, it never even crosses their mind to practice patience. Even though somebody is talking about practicing patience, they're too angry even to hear the word. You know? Some people I say, every time I meet them, say, well, there it is again. Patience. And they don't even necessarily say, oh, yeah, thanks for reminding me. They just kind of go. Well, how am I supposed to do that? Well, then see, there's laziness comes in. I can't do that. I don't know what that is.

[37:29]

And the practice of giving is for stinginess. Most people have some stinginess in them someplace. Most of us have someplace that we don't want to give. But we don't necessarily go around with an articulated sense of, I'm holding on to it, I'm stingy. Most people don't walk down the street saying, I'm stingy, I'm stingy, I'm stingy. When somebody asks you for something, you may feel, oh, maybe I'm being a little stingy now. You might notice it then. Which is good to notice it. Oh, there it is. That's good that you notice it. But now, in this room, nobody's begging from you. But when I bring up giving... it surfaces, it potentially raises the issue. So the fact that you come here and I bring up all these words, then you've got to think, giving, being careful of everything I do, patience, enthusiasm, concentration, that's a lot of practices.

[38:40]

So you walk away and you feel like, you know, I have just kind of like challenged you. And challenge, you know, it means insult. It's when they slap each other in the face in France, you know, with the glove. It's challenge. So when somebody brings up all these practices, it's a little bit of a challenge, a little bit of an insult to your homeostasis. You're getting by, sort of, through the day, and then somebody brings up all these issues, it's like, geez, how am I going to do all that? Well, you don't know. But let's just, you know, get it out on the table that here's all these practices to do. And this is actually, these practices are ways that you're kind to yourself. So part of what you become aware of when you hear of all these ways to be kind to yourself is you hear of all the ways that you can be kind to yourself that you're not practicing. And you feel like, eww. So, I think that

[39:47]

the course being hard or that the course shows you how hard it is to be fully alive, I think that's like you're hearing me. It's hard to practice giving. Even practice giving a little and practice being conscientious a little and even practice patience a little and even practice enthusiasm a little and even practice concentration a little. All those, to activate all those different dimensions of compassion a little, It takes quite a bit of those practices. Because even to do one of them requires the other ones. So you can't really do them without doing the other ones a little bit. So when you start thinking about it, it's really a big job. It is a big job to be compassionate. It's not a little job. It's a big job. It's a big job for a big person. So this is about being a big person. This is about being a big person.

[40:50]

Not a little person. Not somebody who is just kind of like pretending to be okay and not considering the vast potential of human life. But just kind of like, not even let me get to the day. Let me not notice the day. So these practices are not easy because we're not used to doing them. And because we think we can... I don't know. I don't know what we think. Do we think we can, like, get by a day without practicing each of these practices? I guess some people do because they don't even think of them. And they don't usually happen just by accident. They usually happen by actually intending to do them, intending to enter them. Some people are generous, but usually the way we're generous is the ways we already feel good about giving, which is fine.

[41:59]

But there's ways we don't feel good about giving, and then we have to work at those. There's stinginess in us, and the practice of giving is to notice the stinginess, but it's not pleasant to notice stinginess, but that's part of the job. To think about giving is good, and you don't necessarily feel stingy when you think about giving, but if you keep thinking about giving, the more you do it, the more you start to notice the places where you don't want to, and that feels kind of, it's difficult. Now, I'm very happy to hear that after the initial shock of me reminding you of all these practices which are available, you know, that you feel kind of, I don't know what the word is, noisy for a while, that then you think about some of the instructions, you put them into effect, and then you feel better.

[43:05]

You feel better because you're doing these practices, is that right? And you feel bad when you're not doing them to some extent. Well, sorry, but you're supposed to feel bad when you're not doing them. Not doing them is another definition of feeling bad. Being happy is doing these practices. But they're not easy to do, so it's hard to do the practices that train you for a happy life. It's hard if you're out of shape, if you haven't been doing them. And even if you've been doing them, still the parts that you haven't, the aspects of the practices you haven't moved into yet, it still kind of bothers you not to do those parts. But the more you do these practices, the more you are able to face the areas in which you're not doing them.

[44:06]

The reward for doing them is to notice the areas that you're not doing them, that you didn't even dare notice before. You know, it's like stabilizing the mind or calming the mind is similar to these other practices in that if you come to a surface, like if you're sanding wood And you usually start with rough sandpaper. And you sand. You sand away the roughness that this sandpaper will remove. And after you do that, you start to notice scratches that you couldn't even see before. Then you take a sandpaper that will remove those scratches. And you notice scratches, even more subtle scratches that you couldn't see until you remove that next level of scratches. And you keep doing that. And sometimes that you finish before the table's gone.

[45:07]

And you get to a place where you can't even see any scratches anymore. And it's like there's no sandpaper you can use that won't scratch it. Then maybe you start using polish. And you start polishing with like liquid polish or something. And then you start noticing some scratches you couldn't see before, and so on. most of these practices are kind of like really like they can go a long ways like patients can go to a point that's sort of beyond what we can conceive of at this point and there are people who have become unbelievably patient so that so that no matter what was happening to them they wouldn't like try to hurt anybody back they could remain loving no matter what people were doing to them And so Buddha actually said, you know, if somebody comes up to you and like is really mean to you, I mean really mean, like really mean, if you get angry at them, you're not my disciple.

[46:22]

Does that mean we're not Buddha's disciple? Well, at that time when we get angry, we're not. We're supposed to practice patience when someone's being cruel to us. It doesn't mean that we can't say to them, would you please stop? Or, I have something better for you to do, just a second. Or, prevent them from doing this harm to you, but not getting angry at them, which interferes with your cleverness or your creativity or your helpfulness. Not wanting to hurt them because they're hurting you. Well, how are you going to do that? Well, you have to be able to practice patience because our natural reaction... if we don't practice patience when we're... somebody harms us, our natural reaction then would be to skip over the patience and move on to the counter-attack. People tried to hurt the Buddha, but the Buddha didn't attack them back.

[47:37]

Buddha came back to them... at them with L-O-V-E. You know, and not just love, like, oh, you're so sweet for beating me up, but more like... Something to snap him out of it and show him something much more interesting than what they were up to So you maybe know the Buddha converted a mass murderer a serial killer Who was in the process of trying to kill him? He didn't think, how insulting. You're trying to kill the Buddha? Well, forget it. Don't you know who I am? That would, like, really be a waste of your time. Plus, you know, I'm really special, and how could you possibly not appreciate me? And he didn't get into that. Matter of fact, he walked between that guy and somebody else he was trying to kill to stop him. But then the guy just tried to kill him. But he was so skillful that he snapped the guy out of it.

[48:42]

You know that story? This guy's running after him to kill him. This is a serial killer. No kidding. They had serial killers back in the time of Buddha. He killed serially, plus he sometimes killed large groups of people. And he was chasing the Buddha to kill him. And he's running after him and he wasn't catching up to him. And the Buddha was walking at kind of a normal walking rate. And he yells out to him, you know, as he's running. I think he calls him ascetic or whatever. Hey ascetic or hey yogi, what's going on here? Why can't I catch you? What are you doing? I'll put in parentheses, what kind of magic you've got going here? What are you doing there that I'm chasing you and you're walking and I can't catch you? The Buddha says, you can't catch me because I've stopped. I've stopped greed, hate, and delusion. I stopped hate because I practiced patience.

[49:48]

Because I practiced patience, you'll never be able to catch me. I'm not here for you to catch I'm here for you to learn from and a guy snapped out of it and became a monk a great monk actually so but is that easy no it's easy to be that patient no how do you get that patient practice is it is it hard to practice Yes. It's hard to practice when you're in pain, when people are cruel to you. It's hard to practice patience. Is it an incredibly great virtue? Yes. Is it the case that no matter how good you are at it, you can probably get better? Yes. So it is hard. And again, I really appreciate that you've listened enough to hear

[50:54]

and be aware of what's before you, of the program, of the prospect, of the course of study that's before you. It's a big, big deal. And when you first hear about it every week, I can see how you get a little or a lot noised up, agitated. may be frightened too about how am I going to do those practices tomorrow generally speaking I don't think that's a good question I mean well it's how am I going to do the practices tomorrow it's good but don't like think about don't ask the question but don't think about how you're going to do it can I just say a little bit more before I respond to you Dorit If I think about my days, I don't feel good.

[52:04]

So I generally don't. I have some vague idea about what's going to happen, but I try not to think about it because my vague idea of what's happening is such that if I think about that vague idea at all, I don't feel good. Even though each thing I feel very honored to be... I feel honored, for example, to come over here and do this class with you. But if I think about this class beforehand, about what I'm going to do or how I'm going to be, I don't feel good. But if I think about being the way I am now, that's how I feel good about doing this class. So if I think about how am I going to do the practices which I'm recommending tomorrow, I can generally think, well, geez, I would like to practice those practices. But if I think about whether I'm going to be able to do them or not, and what if I don't, I don't feel good. I just commit myself to try to practice them in each moment as the moment comes.

[53:14]

But if I think about all the moments that are coming and all these practices I have to do in each moment, I don't feel good. So I've learned not to do that. And I don't do too well, but I do about as well as I'm going to do. Plus, I don't feel nauseated all the time thinking about this great job I have before me. Dorit? Say it again. You mean you're waiting for the times when you will be patient? Impatiently? What do you mean? Impatient for the times you're patient. Well, for the times when I am connected and feel patient and in the moment and loving. Yes. And the world is singing to me.

[54:17]

Yes. And I can give people what I feel I should be giving people. Those moments which do come every once in a while. Yes. And then they're gone. Yes. And then I tell myself, well, that was that moment and this is this moment, but I still feel very impatient to get back into that. Space. Even though logically, of course. I mean, I understand logically the thought of that, not being in control. No, well, yeah, so you're impatient with your impatience. Yes, exactly. Right. Which we're sort of saying a little bit. Yeah, so we have to be patient with our impatience. Buddha strongly encourages us to be non-violent and to be harmless. Strongly encourages us, but Buddha doesn't get angry at us about it when we aren't.

[55:22]

Buddha's patient with us as we learn at our own rate the teachings. Now, there are cases where the Buddha seemed to be brusque, or even almost harsh with people. But generally speaking, aside from those cases when hopefully those were helpful exceptions to the rule, the Buddha is patient with our impatience. So the Buddha would recommend to us that we be patient with our impatience. But some people have their patience is weakest about their own impatience. Some other people are impatient about other things about themselves. But a lot of people are really impatient with the fact that they don't like other people. That's really hard on them.

[56:24]

Some people, it doesn't bother them so much. Their anger doesn't bother them as much. They're more comfortable with it. And in a sense, they're patient with their anger. And in some ways that's good that they're patient with their anger because then they can look at it and see how it works and then see, that's not so good. It's really not good at all. It's terrible. But not be angry at themselves about it because they might not even be able to see it if they're angry. Yes? First, I'd like to thank you for explaining what happened to me last week. As you were talking, I realized I had a very difficult week. And as you were talking, I realized when it started becoming exceptionally difficult was the day after, Wednesday, and I decided to do my homework assignment, which you had asked us to, you know, when you look at the face, just look at the face, hear the sound, just hear the sound.

[57:37]

And so I was practicing that Wednesday, and I realized I'm so far from being able to do that that... And realizing that, I went into this criticism and became completely impatient myself. But now at least I understand what happened. You understand what happened? And also I might point out that when you start to know, if you're trying to practice just letting, when you see a face, just let the scene be the scene and you notice that you don't do that, Noticing that you don't do that is a cognition. Okay? I became angry more than I normally become angry. I became resentful more than I normally become resentful. It was just... It was awful. Yes. Or maybe I'm always that way and never knows how to... It's hard to know whether we're, you know, whether we just start to notice things about ourselves or whether we actually become more that way.

[58:47]

But I really, it's hard to tell, you know, because we don't have a control group on each person. But I think it's that we just start to notice. Most people have not, you know, been able to actually assess their condition. Because, you know, there's so much to assess. We just, we have trouble paying attention to how we are. And so when we start looking, a lot of us feel like maybe we're getting worse than we were before we started to look. But I have myself noticed that when I see people, you know, I meet somebody and I say, well, take a look at yourself. And then they come back and they tell me all this terrible stuff they find, but I didn't feel like they found a bunch of stuff that wasn't there before.

[59:52]

It isn't like I thought, well, this is really a terrible person. A lot of people come back and report to me what I hear from most people. that they find out about themselves. I mean, this is really funny. A lot of people are totally shocked. They're like those other people. I mean, I see, you know, this person's got anxiety, that person's got anxiety, this person's stingy sometimes, this person's impatient, this person doesn't pay attention, this person's distracted, this person's, you know, agitated, this person's lazy, this person's, you know, I see that. I see that, like, quite frequently among most people. So then I suggest some practice and the person looks at themselves and they find out that they're like these other people that I see, but they're totally shocked that they're like that. They know that other people are like that.

[60:58]

As a matter of fact, one of the few things that they do know about themselves is that they really don't think much of other people who have all these problems. But that they're like that, this is like horrifying. But it's not, you know, to me it's not so horrifying that people are like people. I think it's kind of like fairly normal. Don't you think so? But what's strange to people is that they are like the other people that are normal, or that are usual. I guess we think that normal is for me not to be like those people. That's normal. Being like them is to be, well, you know, have problems. Be, be, well, you know, be defective. Yeah?

[62:04]

It also seems like in my experience, I also get into another trap of contemplating over patience and then immediately coming up with an idea of what the right patience is and the wrong patience. excuse me I just took a tick off rod tell me again so you're you're doing what you have idea of a patient's practices right and wrong could you put this out the window I For me, that feels like I'm in trouble because I only have a concept of my own that I think is right or wrong. And then I think that... Wait a second now. You're saying you're practicing patience? Is that the situation? I have... First I think I should... The should word comes out.

[63:08]

Oh, you do that? You do that? Okay, so... Well, why don't you forget that and drop that should practice patience. Why don't you just forget that? Do that practice called forget that. And then ask yourself, do you want to practice patience? Drop shoulds about all this stuff. There's no shoulds about any of this stuff. When you get really advanced, we can give you a few shoulds. but I don't think any of you are ready for a should practice as far as I know. Maybe some of you are really like way out there, really, really developed and you can try on a few shoulds, but most people that I meet are not ready for shoulds. Uh-uh. Or even oughts. Or even needs. I think the important thing is do you want to practice patience? Work on that. Now, If you're practicing, I want to have patience, then what would follow from that?

[64:13]

Any problems with that? When I want to, I also realize the two things that I realize about that is the should and the I. Well, see, that's the should. Once you have the should, then you're going to get into right and wrong. Because if it's should, then you have to do it the right way. If it's should, you can't do it the wrong way. Should doesn't allow any room for mistakes. So you got the should, then you get into right and wrong, then you're pretty much done for. You're not going to be able to practice patience. Patience is about, yeah, I did it wrong. Yeah, I did it wrong. Uh-huh, wrong, yeah. Mm-hmm, wrong, wrong, wrong, yeah. Mm-hmm, wrong, wrong. Yep, mm-hmm, wrong. Mistake, yep, mm-hmm. Screwed up, yep. I was impatient, uh-huh. So you really got to get rid of that should, Marianne, Because a whole bunch of junk, you're just going to get more and more fall down the should hill. And I found it really helpful to be just open to the experience of patience.

[65:20]

That my willingness is to be open to the experience of patience. Yeah, and open to the experience of impatience, too. Be open to impatience. Be open to not practicing patience. You look at patients and what? You look at patients and you see all the impatience, right. If you don't look at patients, you might or might not notice your patients' impatience. You might or might not. But if you look at patients, you probably will notice your impatience. But if you don't look, who knows? Some people don't. But again, if you don't look, you're not going to see it. As soon as you see it, you're looking. But when you intentionally look to see what the practice of patience is, you will notice impatience because everybody, except the most advanced practitioners, is somewhat impatient.

[66:27]

There are situations when we just simply look. from our life and try to make the world different from the way it actually is and even be violent about it or cruel about it. Most of us can be pushed to that point. But even before you get to that point, you can be a little bit impatient. Most of us will notice our impatience if we start practicing patience, plus we'll also If we look at all these other practices, all those practices that we're not good at will be somewhat painful to look at and embarrassing. And then that will be painful too. But it should be painful. It's good that you're not comfortable being stingy. That's good. If you're comfortable being stingy, you're really sick. If you're stingy, you're a little bit sick. But if you're uncomfortable being stingy, that's your healthy part that's uncomfortable. Buddha is not impatient with you, but it hurts Buddha when you're not patient.

[67:33]

Buddha is not impatient with you, but it hurts Buddha when you're stingy. Buddha is not impatient, but when you're nasty, it hurts Buddha. Because it hurts you. That's why it hurts Buddha. It hurts us when we don't love. It hurts us when we're not compassionate. That hurts. We feel bad when we don't practice compassion. If you practice concentration, you feel good. If you practice giving, you feel good. If you practice patience, you feel good. If you practice the precepts, you feel good. If you practice enthusiasm, you feel good. These things are good, and you feel good about how good they are. If you don't do them, it's healthy that you don't feel good about it. That's like the Buddha. But you need patience to face the fact that you don't feel good. Otherwise, where's the motivation to do the practices that will make you feel good?

[68:38]

Well, it's hidden. It's being distracted because you're not noticing how uncomfortable you feel when you don't do what you know is what you want to do because that's your happiness. But forget about should, please. It's not should, it's that you want to. Now, in other cultures, you know, Chinese and Japanese Zen masters say should quite a bit. I don't know, you know, over in those countries, when they said should, it hit a different psyche. Those people didn't go crazy when they heard shoulds. But in America, I think maybe it might have something to do with the fact that we are, you know, we live in Rome, you know. We live at the center of the empire of the planet. We are in, you know, We're at the power center, you know. We're at the part of the world that tries to control the rest of the world.

[69:42]

So I think maybe the should in Rome means a different thing than the should means in other places. We have this special strange situation that makes us kind of like very, we have to be very careful about pushing ourselves to do anything. But I just noticed that a lot of things, a lot of instructions of traditional Buddhism don't work in America. Shuds don't work. Americans freak out when they get into shuds. We don't need shuds here. If we lived in Bolivia, maybe we'd need shuds. But in America, you don't need shuds. You're living in a place where you can actually deal with what you want. And, you know, it's there. So what do you want? Do you want to do these practices? And if you don't, do you want to practice the precept of telling the truth?

[70:48]

Do you want to practice telling the truth and tell the truth and say, I don't want to do these practices. I don't want to practice patience. I don't want to. I want to be angry. I want to be lazy. I want to be stingy. I want to be distracted. And I want to be angry. I don't want to do those practices. You can admit it. You're safe. You can say the truth. about not wanting to say the truth. You can also lie, but you'll... But if you lie and you come to this class, you're going to be bothered because I'm going to remind you about telling the truth. And then you're going to have that problem all week. Oh, God, not that. Telling the truth. Can I start next week? So I gave you a kind of a practice which is... Last week was a practice more about... It was both stabilizing and insight practice of letting the seen just be the seen and the heard just be the heard.

[72:16]

It was both insight and calming practice. This, the practice with the mudras, in some sense, a little bit more of just a calming practice. The practice last week was the practice which would teach you to have insight into the reality that there's nothing out there. this practice of working with the mudra will help you take care of yourself and be present. And then you can do this other practice at the same time. But the mudra, this mudra presence will, you know, be a test for yourself to see if you're, you know, if you're here

[73:21]

It'll be a way for you to take your seat and be present moment by moment. Then when you're present, then see if you can just let the seen be the seen, the heard be the heard, the smelled be the smelled, the tasted be the tasted, the touched be the touched, and the thought or the cognized just be the thought or the cognized. You can put these two yoga practices together. Does that make sense, to put them together? One is more to work on presence. The other is to change the way you see. Not to change the way you see, but, yeah, change the way you see from seeing something out there, hearing something out there, thinking something out there to have just, they're just the scene, but it's not out there.

[74:23]

It's not out there, you're not over here. You eliminate the duality from your vision by that training. So one is taking, being present, being stable, being here. The other is a practice to cut through the duality in your mind. I gave you that practice last week, but I gave you that practice as following, talking about practicing the middle way of avoiding these extremes which, again, take you away from where you are. So I'm going back and forth between practices which help you be here and practices which help you cut through the duality that arises in being here. Because we think we can be here as subject and object. We think we can have a life where there's me and you.

[75:29]

I think I can live as me, separate from you. But first I have to be willing to be here with how it feels. for me and then look at whether I can just let you be you without adding or subtracting anything from that until there's just you. And then there's no you and me. Yes, Dorit? Pardon? I literally mean there's nothing out there. But what I mean is that it's not that there's nothing out there in the sense that there's nothing out there, okay? But just that everything I see as out there is not out there for me. Like I'm looking at you right now, but what I'm looking at is my own mental functioning.

[76:40]

I'm looking at an image of you in my mind. I know you're out there, yeah, but you're not really out there separate from me. You don't exist separate from me. That's what I mean by out there. Out there on your own, on your own terms, separate from me. That's what I mean by there isn't anybody out there in that way. Well, anyway, you seem to feel that there is somebody out there, right? You seem to feel that. Is that right? Well, that you're out there or that I'm out here. Do you feel like I'm out here separate from you? Okay. So I'm saying that is literally, okay, not true. And what is literally true is that we do not exist separate from each other. That's literally true.

[77:42]

But it's also true that it appears instinctively to us. There's an instinctive appearance that we feel that people are out there on their own, separate from us. That is a human instinct to see things that way. But it isn't that way except for our seeing that way. You take us seeing it that way away, Okay? And it isn't that way anymore. There's no reality like that aside from that we see it that way. I guess I would just have to experience it. You have to experience what? What you're telling me because it's not making any sense. But you can start by working with what you do see, right? You do see that something's out there, right? That you say. And that, you can start with that. So you do have that.

[78:46]

So you see me as out here, right? Separate from yourself. Right? So the exercise is to let what you see just be what you see. That's it. Not have it be out there too. I understand you can't do that, right? You don't get it, right. So you wouldn't be able to do it either if you couldn't get it, right? No. No what? I don't understand how I can see you out there but not But just see you out there, but not feel you out there. No, I didn't say see me out there. I said let the scene just be the scene. That's different from making the scene out there.

[79:48]

Like I can look at Terry. And see Terry without thinking Terry's out there. I can just let Terry be Terry. That's it. Let what I see be what I see. I have this other thing which is that he's out there. I have a concept that he's out there. And you seem to have that too. From what you say. And most people do. You're not the only one. The training is to let go of this concept that what you see is out there. But it's a training experience. So Linda was saying she was trying to do it and she couldn't do it. Because we have this instinctive thing to think that things are out there. So this is a training to, you know, to reverse the process of our instincts, which is that People, other people, are actually out there separate from us to try to see them as what they, well, anyway, what they actually are is that what you're dealing with when you see people is a visual impression.

[81:05]

You're not dealing with the person. You're telling me you're out there, but I'm not dealing with you being out there. I'm dealing with my vision of you. And when I stop looking at you, you don't say, my life's over. Do you? Pardon? No, no. You're not out here. You're where you are. You're not out there. You think you're out there? Yeah, well, so just think about what you just said, that you think you're out there, okay? I don't think I'm out there. I don't think that anymore. I think I'm here, not out there. Pardon? With everything. I'm not out there. I'm here. Pardon? When I see a car, do I think I'm out there?

[82:08]

Is that what you're saying? It's with everything. With everything you see, let it just be what you see. Not what you see plus being out there. But it is instinctive to see things and think that they're out there. We do that to things. We put them out there. But what you're dealing with is something in your mind. You're not dealing with what's actually out there. That's why I said, if I stop looking at you, you don't disappear, you don't die. You have a life independent of my vision of you, don't you? Yes. Yeah. So I don't actually see you. I just see my own brain functioning. And nobody sees anybody. They just see their own brain. That's the way we function. We're looking at our own brain, which is producing images in response to whatever people are. But we think that what's in our brain is out there.

[83:09]

We do. But when I touch it instead, even if I'm not looking... When you touch it, what you're touching is, you know, what you're touching. In other words, your impression of touching it is what your brain is telling you is out there, not what's out there. Yeah? If two people are looking at the same object and you're asking them to define the object, you're going to get two different, perhaps, explorations of the object. It's still not the object. Yeah, those kinds of things are somewhat enlightening as to what we're working with, especially if the two people haven't yet previously agreed on what they're going to say is out there. We have a conventional reality where we say, you know, that's a wall, so we both think it's out there. But actually, the human being is always working with its own mental impressions.

[84:09]

We do not work with what's out there. What's out there dependently co-arises with us. It has no independent life from us, but we think it does. But the funny thing is, after we think it does, we put it out there, but we're not dealing with it anyway. We're dealing with our own mind. We are what's called totally deluded. We are deluded. And this is not easy for us to admit. That's why you need to kind of like take good care of yourself, because this is just the beginning of your problems. Because we human beings, basically everything we see is the result of ignorance. Yes?

[85:13]

All sense perception is delusion, and there's no way to clarify that perception so that you can actually perceive. No, that's not quite right. To see that sense perception is delusion is a clarification. To see that your perceptions are delusions is a clarification. If you can see that you're making me external as a delusion, that's clarity. That's wisdom. But the clarity of the not knowing, the realization that I don't know. The clarity is that you don't know, and the clarity is also that what you see is a result of ignorance. That's clarity. That's why you have to practice compassion. You have to do the yoga of compassion before you can start doing insight, because insight is very insulting to what you usually think, and that's not easy to open up to.

[86:34]

So you have to be comfortable and patient and enthusiastic and loving in order to face this big insult to your worldview, which is that it's very, very superficial and confused. Yes? Could the Buddha see what is out there as what is there? Can the Buddha see what is out there? As being what is there. The Buddha can entertain the delusion of out-there-ness at the same time as seeing that it's not out there. Most people, when they see things out there, they can't at the same time see that that's an illusion, or when they see that it's an illusion, they can't any longer see anything out there. The Buddha can boast both at the same time. But the training that the Buddha recommended in the exercise I gave you last week is to try to train yourself to just see, to just let what is seen be what is seen.

[87:40]

And when what is seen is just the seen, then there's no out there anymore. Then you don't like identify with it or disidentify with it. It's not out there anymore. And that's a training experience. And that way you can relieve yourself from the belief that what you're looking at in your own mind is out there. But we actually think that what our brain is telling us about, the brain is telling us, the brain is giving us a message and saying, this message is from out there. The brain says, hi, I'm out there. Your own brain is telling you that it's out there. The brain passes you an image and says, this is outside you. And it says, believe it. Because if you don't, you're not going to be able to get through high school. Anyway, sorry to keep you up past 9.15.

[88:39]

@Transcribed_UNK

@Text_v005

@Score_87.0