You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Repentance Beyond Duality

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk explores the theme of repentance, emphasizing the importance of noticing and admitting errors rather than merely acknowledging them in a general sense. This is linked to the discussion of Case 34 from the "Book of Serenity," which juxtaposes the merits and problems of "setting something up" and "not setting anything up" in the context of spiritual practice and the establishment of Buddhist teachings. The speaker examines these dualistic approaches through the lens of Buddhist concepts, specifically identifying them with the three bodies of the Buddha: Nirmanakaya, Dharmakaya, and Sambhogakaya. Through the practice of repentance, individuals can correct errors and return to an awareness aligned with the true nature of reality, beyond the apparent duality of actions and states.

Referenced Works and Concepts:

- Book of Serenity, Case 34: Discusses the idea that setting up any system or teaching can either help or hinder spiritual practice, as it reflects broader themes of transient versus permanent states within Zen.

- Three Bodies of Buddha:

- Nirmanakaya (Transformation Body): Manifestations that accommodate people's needs.

- Dharmakaya (Truth Body): The universal, inherent nature of the Buddha, which goes unrecognized when not setting anything up.

- Sambhogakaya (Enjoyment Body): Bliss arising from the non-duality of the transformation and truth bodies.

- Dongshan and Case 98 from the Book of Serenity: References to transcend the categorization of the three bodies and not fall into duality, reflecting the ultimate approach to Zen practice.

These teachings emphasize the Zen practice of repentance as a means to resolve dualistic errors and move towards a balanced understanding of the Buddha's teachings.

AI Suggested Title: Repentance Beyond Duality

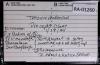

Side: A

Speaker: Tenshin Reb Anderson

Possible Title: Precepts Class - 3 Bodies of Buddha

Additional text: Discussion on 3 Bodies: 1. Nirmanakaya, 2. Dharmakaya, 3. Sambhogakaya

Side: B

Speaker: Tenshin Reb Anderson

Possible Title: Precepts Class

Additional text: With respect to setting something up & not setting up. Repentance - To Admit & Notice Error

@AI-Vision_v003

So part of repentance was to be able to notice error and to admit, to notice and admit error. Not just to admit error in general, like we, in the morning, we chant the confession, but... We also need to actually, it's really helpful if you actually can notice the error rather than just generally kind of like signing on the dotted line that you assume you have all this stuff. But to be aware of it's really helpful. And actually, I kind of wanted to relate, although it may be a mistake, this error making to... to case 34 of the book of serenity where the teacher the statement at the beginning of the case is the teacher says that to to set up a single atom or to raise a speck of dust the nation flourishes if you don't raise up a speck of dust the nation perishes

[01:28]

And that's what the case says. But a longer version of that is, if you raise up a speck of dust, the nation flourishes, but the elders frown. Or actually, they don't relax their eyebrows. They're kind of like, what are you guys doing down here? They keep looking. What are you doing? Instead of doing that stuff? You do something, they keep worrying. You don't set anything up, the nation perishes, but the elders relax. They don't worry. And we discussed and had some length in the Koan class about these two sides, one side of doing something, of setting up a teaching or setting up a Zen center, and all the things that happen as a result of making an establishment.

[02:37]

Politics, business. And you set up an establishment in order to facilitate the practice of Buddha Dharma, but then sometimes the establishment seems to become a hindrance. And so the elders worry. On the other hand, if you don't set anything up, then it's hard for people to gain access, but you stay... You stay pure. And the elders aren't worried about the teaching being defiled because nothing's happening. But in this case, I feel like both of these positions are an error. It's an error to hold to not setting something up And it's an error, well, it's actually an error to set something up, to think you're setting something up, and it's also an error not to set something up. Or rather, if you hold to that, you need to either side.

[03:43]

And the setting something up is, it's called the granting away, accommodating to people's needs. But again, there's consequences of accommodating to people's needs. For example, they expect you to do it again sometimes. And they set up governments to make sure that it will happen again. And they can even become, you know, people will even wage wars to establish a system which they think is helpful. The other side is called the grasping way. You hold to the absolute, you hold to the ultimate. The grasping way.

[04:51]

So one is a kind of absorption in what is positive or helpful. The other is absorption in the ultimate. namely that you don't have to do anything really and because there's nothing really to be done and nothing really happens. So I feel that these two approaches can be equated with different aspects of the body of the Buddha and also can be equated with the precepts in a certain way. And the way I would associate it with the body of Buddha is that the Buddha body has three aspects, can be considered as having three aspects.

[05:56]

One aspect is, you know, it might be nice if the blackboard was kind of like over like that. Then I could write on it rather than climbing over you folks. You don't necessarily have to move though. Setting something up, not setting something up. Or, you know, that something is set up or something is not set up.

[07:08]

Or seeing something set up and not seeing something set up. Think of this in a passive and active way. In a sense, you can tune in on Buddha's body by being aware of these errors. And these errors actually are errors, but they're not errors like you're totally out of the ballpark, because actually you're touching. When you go either side here, you're touching Buddha's body. Both of these ways, you know, have some... There's something... Both of these ways are touching Buddha's body. They're not, like, wrong in the sense that, you know, you shouldn't do them. It's just they're not on the mark. They don't, like, embrace the whole of the project.

[08:12]

You know, the balanced approach to the project of Buddha way. These two sides. And actually they do, I think you could try on actually equating these two mistakes, in a sense, to holding to a certain aspect of Buddha's body. And the way I would set this up is that setting something up is what we call, to have a sense of it, is what we call the nirmana. Buddha. And no every Buddha is a being with circle on it. And Nirvana means like a tr- N-I-R-N-I-N-A. Nirvana.

[09:18]

It means transformation or phantom, fantasy. Or because they're a combination. So it's the transformation body of Buddha, right? The fact that Buddha's body gets transformed into, you know, human form. Or, it even goes so far as to say it gets transformed into... Well, I wish I could go that far. I was just saying... Not setting something up is called, I could say, it's like the darkness in the Dharma body. The key with the circle around it symbolizes the Dharma. The Dharma body, the truth body is Buddha. This is the Buddha body without setting anything up.

[10:20]

But first that's the... ultimate or absolute Buddha body, but a complete Buddha body in a sense, because since there's nothing set up, it's all pervade. It doesn't... you know, nothing can hinder it and it doesn't hinder anything. So, everything in the universe is this Buddha body. You might say, well, then isn't everything in the universe the transformation of the Buddha body? In a sense, no. For example, mass murderers are not really the transformation body of Buddha. However, the dhamma completely pervades a mass murderer's life, isn't hindered by that cruel life. like the cruelty.

[11:26]

But that isn't like, that isn't what's called accommodating people's needs. And, you know, adjusting and teaching in order to benefit people. Now there's another body, which is called, in a sense, the Sangboga. Tamboga means like bliss, but you know, like a real big bliss, like total mind-blowing, body-blowing bliss. The bliss of being connected with all beings. It's sort of what it feels like when you're a member of a Bodhisattva country club. In some sense, it is the enjoyment of the non-duality of these other two bodies.

[12:44]

It's enjoying the non-duality of these two sides, each of which, when you grasp, you're grasping one side of an apparent duality. . So I think this is OK with me, if you try that vision of how these are related then to these errors. Now, if you notice that you're going over to this side and making the error of setting something up, or going over to this side and making the error of holding to the absolute, what you have to do sometimes is that teachers have to do this. Bodhisattvas have to go to make these mistakes.

[13:47]

But if you notice that you're making a mistake, that error is a way of tuning in to Buddha's body, because you're tuning in an aspect of Buddha's body when you notice the error. Noticing error, this particular type of error anyway, which is an error coming from the intention to benefit people. And this is also coming from an intent. The accommodating coming from the intention to benefit people and the holding to the ultimate is coming from the intention to benefit people. But they're errors. They're biased representations of that intention. Or maybe I wouldn't say they're biased representations of them. They are expressions of that intention, but they don't represent the intention. fulfillment of that intention in a balanced, unbiased way. Yes? I don't understand what's going on. How is that incorporated?

[14:52]

And it's like, it thinks to me that I can either set something up or not set it up. And I understand that I can watch how I do set it up or not. So I'm not completely in there, but I can be watching it. But I don't really understand how I can do my actions and combine them or include, embrace those things and action in my daily life. Good question. Do you understand your question, basically? So how I see it working is that you notice... First of all, I guess you have some faith in Buddha. And by genuine faith in Buddha and Dharma and Sākra, by this kind of faith, you, for example, do the practice of repentance, which is said to be... which all Buddhists say, they've all done this practice of repentance, they recommend it, it is the first step of receiving and going home to what you have faith in.

[16:05]

And by faith I mean not that you believe there's a Buddha, you think probably there's a Buddha, or I'm pretty sure there's a Buddha, that's not what I mean by faith. What I mean by faith is that your ultimate concern, Buddha, your ultimate concern is to be awakened so that you can benefit all beings. That's your ultimate concern. And when you genuinely have that ultimate concern, and you're willing to do what that ultimate concern requires of you, for example, practice repentance. If you're practicing repentance as an expression of your faith, Your faith being that your ultimate concern is to go home to your wicked nature. So you practice your repentance. You practice your repentance, you notice that you make the error of not setting something up. You make the error of setting something up. So you become this practice.

[17:07]

You become the practice of noticing that you veer to the side of the body of truth of Buddha, you veer to the side of the body of transformation of Buddha. You notice that. You become the noticing of that. Becoming the noticing of that is called, you know, practicing your faith. practicing your concern. Your concern is to return to the Buddha body, but it turns out that the way of returning, the first step in returning is admitting how you approach it in a biased way. You cannot go directly, boom, straight onto it. That's like, you know, a super mistake. It's a better mistake in some sense to realize that you can approach it by extremes. When you completely become this practice of repentance and already admitting that you're touching Buddha's body in a kind of biased way, the reason for that practice is the bliss of realizing that you really never were ever.

[18:10]

That actually these three bodies, these two bodies are always connected. And then you realize the other aspect, which these two didn't represent, And that is, this doesn't, neither one is mentioning the fact that Buddha's body is, is this, you know, mind-eliminating bliss. Mind-body eliminating, overcoming, liberating, bliss of interconnectedness of all beings, which is a reward, or a consequence. of practicing pretentious thoroughly. And then you really return to your... You experience the joy of having returned through error. Not through error so much, but through admitting your error, you return home. Just like if you're lost, by admitting how you got lost, you get back home.

[19:15]

And how do you admit when you're going home, how do you admit that you're lost? You take a step. And every step is an expression of your being lost. However, if you just be lost and lost and lost and lost, every step you take is not necessarily bringing you closer to home, but is your way to home. The only way you get home will be by this kind of walking, each step of which will be expressing the loss, but also expressing your return. So practicing repentance, admitting your loss, like I was saying last week, diagnosing the illness is the treatment. When you diagnose the illness, you touch the cure. Now, What is important is that you realize that finally you realize that what the Buddha is, is not any one of these three. And in case 98 of the Book of Serenity, a monk asked Dungsan, among these three bodies of Buddha, which one doesn't fall into categories?

[20:31]

Or another way that sometimes the question is asked, how can you not fall into counting? In other words, how can you avoid falling into one, two, or three? Or falling into two, or falling into two? Or falling into all three? How can you, in other words, become the whole picture of Buddha without falling into any category of all three, two, or one? And Dongshan says, I'm always close to this. He doesn't say, I am this. But he's always close to not falling into these categories. So this is a part of me further explaining to you how repentance brings you closer to actually being able to perceive the perfect, the jiva of the Buddha.

[21:35]

or not so much to receive it, but to go back to it. When you go back to it, you throw your alienation from it. And you can express your alienation in these wholesome ways. These are wholesome errors. It's a wholesome error to hold to some principle of goodness. It's a wholesome error to not do anything. In other words, to trust Dharmakaya Buddha to trust that Buddha pervades every single thing. To really trust that. But, if you, but, you know, it's hard not to make an error in that. Or trust the other side, namely, that whatever people need, do it for them. But make the mistake, in a sense, of if you're doing something. But admitting this, it isn't making these mistakes that bring you close to Buddha.

[22:43]

These mistakes are simply expressions of your connection. It's admitting that it's your error that brings you closer, that helps you return. So that's more about repentance and as a warm-up or as an approach to taking refuge in the Buddha and the Dharma and the Sangha. I was about to say that the Nirmanakaya is also like a temple or a garden or something like that. But actually, that's more like the Dharma getting transformed into some form. Dharma also is present in all things.

[23:47]

This is called the dharmakaya, right? The dharma body buddha. But also the dharma gets transformed into whatever people need. In Zen Center, you know, we have certain forms in which dharma is transformed at Zen Center which have been very, you know, accommodated. One of the things we're most famous for is a good food. A lot of people have been found contrary to Buddhist practice through Zen Zen school. So what would you call a rakusa or a nukesa? Would that be an example of the transformation of... Would that be dharmakaya? Well... No. That would be the transformation form of the dharma. Well, you know, you could see... That's a nice question, too. You could see this as a transformation to accommodate people's needs.

[24:59]

But actually, I think that it's often that's not what it is. Now, if people were cold... you know, and we had like nice, I don't know, wool robes in there, and we had our full-sized ones. Then giving person, then some people were sitting out in the woods or out in the snow, and you felt like they needed some coverage. Then to use this robe to keep warm would be a little bit more like accommodating to their knees and trying to encourage them. But in some ways, this robe, from some people's point of view, is more like The Dharmakaya, because they look at this and they say, this is a funny outfit. It's not very stylish. And it's weird. It's supposed to be made of what originally like toilet paper. They didn't have toilet paper in the 1880s rags.

[26:02]

So the rags that they had used for that purpose that they'd throw away, Buddhist monks would go pick those up in the garbage cans and wash them and bleach and kind of like dye them together in some kind of color which they would become somewhat similar and then cut them into rectangles and patch them together again. Now some people would not consider that really setting up that much. They would think that's really minimalist or that's not accommodating people's needs much. And some people, so they would say it's the Dharmakaya, but some people, when they look at this robe, burst into prolific tears of joy. This is also... So they would say that this robe is the Sambhogakaya. This robe, they would say, they would see, this robe represents the union of nothing at all and accommodate April's readings. It's not stylish, and we don't change the shape according to a person's body type.

[27:10]

It's really not that cool an outfit. And at the same time, it is an outfit. It does, you know, it is clothing, and we are accommodating to people's needs, you could say. It depends, you know. Some people think, you might think some people come and they think, well, I, you know, You know, this is like totally cool, this Buddhist scene, and I've seen these movies about these, you know, neat monks who wear these outfits, and you can go to Zen Center and you can actually get one of those outfits made in this authentic way, and it has all this, you know, like totally cool vibrations coming off, you know? And every stitch has like, you know, a religious fervor built into it. It seems like they just, they resonate with, you know, positive energy, you know? That's, looking at the robe that way, it's an accommodation. And in fact, if you look at these robes that the people make them, they have definitely, I mean, you know, they have a lot of energy, which the faithful can easily see.

[28:12]

But again, seeing that energy, at its extreme, when you first start to see these... glow, that's again... then the world is the Sambhogakaya. So accommodating to spiritual materialism... And some spiritual materialists are coming here to get robes. And there's also some materialists, if we really were poor, who come here actually just to get clothes. That's possible, not in America these days. And you could give it that way. It could mean that to the individual. And again, to faithful people, these robes are like the most valuable, precious things on the planet. But again, to a strict practitioner of meditation, these rules mean absolutely nothing. They are an expression of giving people as little... I mean, without violating societal rules and the forms of practice. And Buddha said, don't go around naked with monks, because that was done in those days. He said, wear some clothes, but like, just wear, you know, just to distance yourself from these weirdos, wear some clothes, but make it like, you know, basically nothing.

[29:21]

And show people that the Dharma pervades even a shit cloth. So you can say to Dharmakaya, in other words, anything could be in any of these categories, including this robe. This robe is actually easy to see that it belongs to all three. This robe is a field, a blessing, beyond any of these categories. All the different marks and characteristics you would use to specify where the robe should fall, the robe is beyond that. And in fact, everything's like that. And it's not that things belong in those categories, but just we have to look at ourselves and see, where do we put them? Where are we holding? One day, you can see the world in this extreme. The next day, you can see it in the next extreme. And if you see it, and if actually you see your mind, in your own mind, if you watch your mind put the world into these different categories, long enough, then you would see that faith. You would be rewarded by that faith, and you would see the robe as a ocean of transcendental bliss.

[30:27]

By doing the practice of noticing your mind veer from one extreme or the other to the view of the robe, The Buddha is sometimes described, you know, you may have heard of some pictures of the Buddha being 60 feet tall and gold and had these, you know, rays of light coming out and webbed hands and all that stuff. This is the way, this is what a person of faith can see. And you'd have to talk to them about what they see. But basically, they see these webs between the fingers of Buddhas. In other words, they can see that when a Buddha moves her hand through space, it scoops up innumerable sentient beings with the webbing. No beings slip through with the hands of Buddha. All of them are able to embrace everything they touch, and no one falls through. They can see that. So it's kind of like seeing a webbing in your hands. And also they see these Dharma wheels in their palms and up at the soles of their feet.

[31:33]

In other words, when they see a Buddha raise her hand, they see the Dharma clearly in hand. This is a reward for their faith and their practice of repentance. This is a reward for them sitting upright, watching how things work according to the teachings of the Buddhas. So I would say, I use this example, but anything could fall into any of these categories depending on your perception. And as you study your perception and how your mind works and how you make errors, you more and more tune in the true Buddha, the Buddha which is not any of these categories, but all of them in a non-dual happy family. And if somebody says, do you wish to return to Buddha, you say, yes, I will.

[32:39]

I want to. And because you practice repentance, you say that, and you really feel that that happens as soon as you say yes. You feel confirmed in that. You feel communication between something that the universe has now asked you this question and your response. or you're putting yourself in a position where somebody will ask you that question, and then you're being able to expend your life energy by saying, yes, I will, then you experience the benefit, the merit, the virtue of taking refuge, the actual living function that the refuge comes to you with. It's getting hot in here. It's the one who's up there. So I could stop now for a little while if you want.

[33:47]

I've written for a long time. You want to ask questions about this? I'll just say one more thing, and that is, Dongshan said I always stay close to this, to whatever, to the thing that doesn't fall in these categories. Staying close, if you would, if you would, you know, take more identification with it, then you'd probably fall in one of these categories. And one other thing that comes to my mind along this case is a line, a poem that's in this case, which I think is very important, where it says, this closeness is heartrending if you seek it outside. The ultimate the ultimate intimacy. It's almost like enmity. It's almost like war.

[34:50]

It's like getting two magnets really close together and then, but not, you know, it's not like you smack together. It's very, it's very hard as you get close, as you start closing this gap here. So he kind of like stays close to what it is, he doesn't fall into these categories. And we return to Buddha through our human error, through admitting our human error. It seems to me in both of these classes that I've noticed that this has more of a theistic theme to it than I've heard in any of the classes that Steve's given. And I regret you speaking of it. Tell me about this. theistic thing you see. Well, it was the way you used, how you used the Buddha's name almost as a one of adoration or I would say more of the Christian tradition of how

[36:05]

how I was taught as a child to love God, and I think the terminology just sounds very much of how I was brought up in a Christian belief system, and it's been a little, just been starting. I mean, not that I have any opposition to it, but it's just like, oh, wait a minute, this sounds pretty different than what I've been hearing for the last 20 years. Well, I would say, that when I first started practicing Zen, when I first started practicing meditation, I hadn't heard either about adoration of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. I had not heard of adoring and loving anything, actually. I heard, just sit. However, if I look at the behaviors of the people that attracted me to Buddhism and that led me to the practice of sinning, I did adore their behavior.

[37:15]

I didn't think of adoring, but I said something which is about the most adoring thing I could say about somebody, and that is, I want to be like you. So, Amit, you know, Homage is, for me, I used to think homage meant praise. But one day I looked it up and thought homage doesn't just mean praise, it sort of means praise. But it means more than praise, it means you align yourself with the thing you pay homage to. In other words, you want to be like that thing. And I paid homage to the Zen monk stories that I read. I paid homage to them. I wanted to be like them. I thought if I could be like these people in these stories, that's the kind of life I'd want to have. And I had trouble paying homage to the Christian stories because I couldn't see how I could align myself with some of those stories. Even though I thought they were groovy, I couldn't see how I'd be that way.

[38:17]

So the first step in some ways, in some sense, is homage to something. and adoration of these jewels. But to actually return to them, the actual return, rather than just honoring them, the actual return and integration and embracing them and living with them, the first step in that is repentance. So adoration of the triple treasure is really, well, can I say, it is central. And I think it is not the... It is not the thing that has attracted most Americans to Zen. It was not adoration of each other. It's something which, after the image, the stories of Zen and the artists of Zen goddess inside the door, then this has now become... This is now being brought out of the closet.

[39:25]

And I think part of the reason why for whatever reason why it wasn't brought out in the beginning, is that perhaps people from non-theistic backgrounds who were disaffected or fleeing even from those backgrounds, to some extent, would have had trouble approaching Buddhism. It looked like another one of those things. Even though it isn't, it looks like that in the realm of adoration and praises. Bodhisattvas, the first of the Bodhisattva vows and the ten vows of Samantabhadra, the first one is homage to all the Buddhas. The next one is praise all the Buddhas. The next one is make offerings to all the Buddhas. In other words, turn, tune in, you know, D-U-D-D-H-A. Tune it in. And the way you tune it in is not by spitting on it. I don't know.

[40:27]

Not by criticizing or disrespecting. The way to tune it is to align up with it and praise it and make offerings to it. And I agree that that's not something you might have heard that much about before, especially since you've been out of town for a while. But this is a class on the precepts. And receiving the precepts is the gate to Zen. So what we do is we let people come into the Zen Center and try to practice Zen without receiving the precepts. And they do their best, and they practice, and they do pretty well. Because on some level, probably, they already have received the precepts. But if in their heart they have not yet opened, it's that, yes, I do adore Udā. I do adore awakening.

[41:31]

I do adore the function of compassion which benefits all beings. If they don't adore and align with that, then as they get into practicing Zen, they start to, what is it, they start to slip on the slopes. Because they haven't then, they don't have the resource which is the point of the practice. which is the source of it, which is the beginning and end of it. The beginning and end of Zen practice is Buddha's compassionate heart. It is to set beings free from suffering in all the different interesting ways that they're doing it. And we've got this wonderful practice which works for everybody, but not everybody wants to do it, so we have to figure out some way to get them to do it. And we have to be ready for that to be any form. So we have to be able to accommodate to them, to help them to practice.

[42:33]

Okay, for now? Yes? When you said before about faith in Buddha, you said you don't have to believe in Buddha, or that it's probably Buddha, but what you have to have faith in is awakening. Because Buddha, essentially a Buddha is an awakening. I don't think I said that, but if I did, I don't mean to say that. I don't say faith in awakening or Buddha. I say not that you think that there is one, but rather that your concern, what you're focused on, what your agenda is, the ultimate, when it comes down to it, what you really care about, what you're really concerned about, not a belief. Faith, I don't mean faith as belief in Buddha. I mean, Buddhist faith is the faith of Buddha. It's a faith that Buddhists have, and it's a faith of being primarily, ultimately concerned with awakening.

[43:38]

I'm sorry, I didn't quote you, so... So your statement was that your ultimate concern, your primary focus for Hennepin is the enterprise of the Buddha, which is the way he did it. So in that sense, what I feel about that, because I also have this typically American attraction to the practice, which is not, I'm not interested, at this point in devotional practice. I don't believe, in a sense, in the deities that we've been taught about. But... Taught about where? Well, here. I thought you were talking about deities.

[44:40]

Okay, well, for one, Well, there are Bodhisattvas who I don't believe are historical figures that we hear about. And Buddhas, other than Shakyamuni Buddha. You don't believe in them? Well, I have them other than this, but they exist. But again, that's belief. That's not faith. I don't believe in them What I believe in is like I believe that Stuart weighs over 100 pounds. That's the kind of stuff I believe in. That has nothing to do with my faith. My faith is, I don't believe in Avalokiteshvara. I don't believe that if I do this, then that will happen. That's not my relationship with Avalokiteshvara, but I have faith in Avalokiteshvara, and my faith is that there's nothing

[45:44]

I care about it as much as being Avalokiteshvara. But I don't believe in Avalokiteshvara. I don't think there is an Avalokiteshvara or isn't an Avalokiteshvara. And my faith is what I really care about is having a relationship with Avalokiteshvara which doesn't fall into any category of existence of me saying there is Avalokiteshvara, there was Avalokiteshvara, isn't, there won't be, there never will. That's all those categories of existence. My faith is, I don't want to have anything to do with those. As human being, I do slip into those categories. That's what I repent for. My faith is that repentance for saying that there is all that we just borrowed isn't getting into these kinds of errors, admitting that kind of error. My faith is, that's the way I want to Not my faith is that if I live that way, things will be good. My faith is that's the way I'm going to live.

[46:48]

Living that way is my concern. So I'm not teaching you that there is a thing called Adlopiteshvara or there is a thing called Buddha. Because if I teach you that, then if you get close to this, it's just going to be heart-rending. And if you're far from it, it's going to be heart-rending too. What I'm here to say is this is my faith. I'm just showing you my faith. My faith is, what I'm concerned about is to have the correct relationship with everything, including all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. It just turns out that the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are the ones who are saying, get me to the correct relationship. And that means don't put me in any existential category. Don't say I exist, don't say I don't exist. That's what their teaching is. So, So, I mean, all I was trying to say was, approaching this, I come because I would like to wake up.

[47:56]

I would like to awake, and that is my primary concern. It is not, but you're sort of saying that without a certain, is that what you're saying one needs in order not to slide down a slippery slope? the strong commitment to awakening? Is that what you mean? Yeah. Yes. Okay, so... You don't have a question about that? No, I don't have a question about that, but it sounded... I was concerned that there was some devotional kind of thing you were saying. What do you mean by devotional? To be... We have the expression to be totally devoted to a mobile city. You mean that phrase, right? Devotion means... What does devotion mean? It means to devote, to have the intention to do... It means the D is an intensifier for the devote. Right. All right? You know, devote... I can see devotion as devotion to practice or devotion to sin.

[49:01]

Right, that's the devotion I'm talking about. I'm talking about devotion to practice. In other words... You're concerned about practice? Is that what you're concerned about? You want to live like a Buddha? Is that your ultimate concern? Well, then you have to devote yourself to that. Vote means you have to use whatever will you've got, whatever intention you've got, you've got to do it. In other words, intensify that intention so that all your intention goes to what you've decided is number one. If sitting, which you think is the practice that the awakened ones have transmitted, if you want to do that practice then you devote yourself to that practice and you become devoted. Now, you don't have to say, well, I'm a devotee, or I'm a devotional type, or anything like that. You can say, I'm a non-devotional type. I'm here to say that I'm not into that stuff. I am totally devoted to this thing. It's one of these little contradictions that I represent.

[50:04]

Because I'm a human being, and human beings are contradictory critters. So I'm not telling you you have to be devoted, but I'm telling you you have to be devoted. You have to give yourself entirely to what you think is most important. You can't compromise with what you have no compromise about. I didn't think I was a devotional type either. I got exposed to these teachings, if you're sorry to say. As a situation, he was very quiet about this. But just before he died, he said, Adoration of the triple treasures is pretty much all it's about. He knew he wouldn't get in trouble anymore. He said that in the summer, just before he died, he said, yeah, really heavy on the precepts and real heavy on, not really heavy, just very pointed about the fact that this stuff is essential.

[51:08]

So, in a nutshell, say that a complete practice would encompass not just sitting, I mean, you can just sit to a certain degree, but let's say when the hill gets steep and you start to slide off, then you have to go to the other side of the same coin, which is this. Go to the other side of the same coin, which again I've mentioned this morning, You know, it isn't by self-power that you can practice repentance. Because, you know, you try to practice repentance, I said, you know, like admitting your errors, but human beings have a hard time admitting their errors. Or like, you know, how you get concentrated by self-power. The road to concentration, again, is by basically admitting how confused and distracted you are and how agitated your mind is. If you don't admit how agitated you are, you try to, like, get concentrated and you keep slipping again because you don't admit that you're distracted.

[52:20]

Well, what if you can't admit you're distracted? Most people can't. Well, fortunately or unfortunately, you don't do this practice by yourself. It isn't something you do by yourself. And it isn't something that somebody else does, so you can't just sit back there and wait until you get concentrated. Concentration score arrives to save you. You have to... You have to find the straight path where other power and self-power are transcendent, where you own willpower. So when the path gets steep, then you say, OK, now that I can't do it, now would you people please help me? They might just say, well, what do you ask me now for? Why don't you ask what was level? You just do it, and as soon as it gets level again, you just get very easy, you're just going to forget about us. They get, you know, petty about this. These non, these beings which don't belong to the existential category.

[53:25]

And Buddhism is not theistic or deistic. It's non-theistic. It's not, it's not non-theistic. It's non. Non means, you know, We have, you know, we have a balanced relationship with theism. It's, it's... It's cool. It's too naive to believe in the deities as existing. It's too coarse and Protestant or whatever. I don't know what.

[54:27]

Just too cold and dry and uncolorful to say that they don't exist. Basically, we should treat everything with the same respect that we treat reality. We shouldn't insult things by saying they exist and insult them by exaggeration or underestimation. We shouldn't insult them by saying they don't exist by underestimating them. We shouldn't insult them by saying they both exist and don't exist. And we shouldn't insult them by saying they neither exist nor do not exist. Neither exist or not exist, whatever you're about to say. You should do that with deities, with divinities, with gods, with goddesses, with people, with plants. Everything should be respected in that way. Again, respect means look again. Look again. Somebody's there. Look again. Are they really there? How are they there? And again, one of the Zen stories that attracted me, that I wanted to align myself, that I pay homage to, was a story where a guy, basically no matter what you said to him, he said, is that so?

[55:38]

Is this what's happening? How's it going? Good. Cool. What's your name, Bruce? It's like before. Ever changed? We'll discuss that later. Lots of different parts. I'm in the same class, but it's not power into an expert. I'm trying to get an idea of whether or not we're looking for sort of a balance in the types of errors that we make, or at least the types of errors that we discover.

[56:49]

between setting up and not setting up? In other words, can there be something like, gee, I'm not setting anything up. I keep seeing myself making the error of not setting anything up. I've got to start setting some stuff up. Is that an appropriate way to practice this, or not? Time. Let's see, what is that? That is... Well, I won't say it's not... I don't want to tell you that that wasn't appropriate, but I would tell you that that's not what I mean by repentance. Repentance is, if you notice, okay, here I'm practicing the grasping way. I'm very real strict and pure. Here I am off in the mountains eating mushrooms and starting to... because I don't want to participate in the evil empire. I'm just, you know, here I am again and again being the purest. So just every day you kind of get up and say, there, I'm making that mistake again.

[57:55]

Yeah, and then not just when you get up, but the rest of the day. Right. Here I am on this trip, here I am on this trip, [...] same trip, over and over and over again. And you might think, well, maybe I should switch to some other trip. You might think that. But it isn't that you're supposed to think that. You're supposed to admit what you're thinking. So if you think, well, maybe I should switch, then you admit that that's the thing. Where does that fall? Repentance is not to do something different. is to admit what you're doing. Admitting your error. See, admitting your error and then by thinking, well, now that I've noticed my error, I should do something different, that is the error of thinking that your fantasy of what you would do now next, that that would match reality. Which type of error is that? It's this kind. It's this kind. It's thinking that you set something up, you should do something.

[58:58]

But it's an error because instead of just saying, well, I think I'll just set something up today, it isn't that way. You think, well, I'm making this error, so now I'm going to do something called not an error. In other words, instead of making error, I'm going to do something to correspond to reality. But I'm going to do something to correspond to reality. I'm going to do this. To not do something, to correspond in reality by not doing anything is a big mistake. The point is you think, here, I'm making a mistake. I'm getting sick of making mistakes. I've been repenting long enough. Now I see my problem. Now I'm going to be a good boy. And I'm going to do this. That's error on the other side. But if you think that, well, now I'm going to do something. And you notice what you're not just saying, I'm going to do something. But you think, now I'm going to do something different from the errors I've been doing. When you notice that, then you say, oh, that's an error too. Then you have committed an error because you, in your heart, thought you were going to do something which wasn't like those errors over here.

[60:00]

Not only was it different, but it wasn't a mistake. That's an error. Some other people do stuff all the time, and they start to notice, I'm doing stuff. This is actually an error. There's problems over here in this trick. They say, well, I think I'll give this up and do this other thing. But rather than I think I'll make a different type of mistake, they think they're going to do reality. In other words, they think they can do the middle. If they don't do the middle, you cannot do the middle. You can only do error. The middle can't be done by a human being. The middle is done not by self-power, and also the middle can't be done by somebody else winding you up and sending you on that trip. The middle is the transcendence of somebody else living your life for you, some big Buddha or something, some causal stuff causing you to be this way, and you do it on your own. So a lot of people get into these ruts, have ruts. They are in ruts. Then when they notice they're in ruts, then they, of course, just as soon have enough noticing of the rut.

[61:04]

I've been taking inventory on my neurosis for a long time. I think I'll do something different. That's a break in faith. But if you notice that you could do something different from error, you can never do anything different from error. Anything you do is an error. Because nothing you ever do but yourself. And also it is an error to think somebody else is going to do it for you. Those errors are what you can do or somebody else can do. What somebody else can do is an error you can do as an error. What's not an error is something you can't do. However, the road of non-error is opened up by admitting your errors. The faith that leads to the practice of repentance and becoming repentance, if you become repentance, all you are is just make an error, admit an error. Make an error on the other side, admit an error. You become repentance. As you become repentance, this road in the middle starts to open up, and it starts to be lived.

[62:09]

and you go back, and this is taking you to go back home. Instead of going this way, which is the direction caused by making errors and not admitting them, in other words, making errors and think, well, I did another thing right. Well, I did another thing right. Well, I'm practicing Buddhism now. Now I'm going to practice Buddhism in different ways, because now I'm supposed to do it on this side, and now I'm going to do it on this side. Ah, here's a dharmakaya buddha. Here's a dhammakaya buddha. I'm really grooving on buddha. This is called making mistakes. I'm doing the practice. I'm doing buddhism. That's evil. I'm doing buddhism. Doing those things and actions that come from that attitude send you down this way. This is the direction of birth and death. This is causally produced birth and death this way. Misery. You start to, as you're flying away from Buddha, towards misery, by making these mistakes and now noticing them, and then you hear about, well, if you want to turn this around, the first step in turning this around, going home, is to admit your errors.

[63:27]

You start saying, oh, okay, all right, okay, okay, this is, okay, okay, I'm in. As soon as you admit that it stops for a second, you start turning around and going the other direction. I made an error. I made an error. I made an error. And as you start to notice errors, you start to turn around and go in the other direction, towards Buddha, away from misery, away from birth and death, towards stopping birth and death, called nirvana. Start going the other way. Can you repeat the birth and death step? Got it. I brought it with me when I came here. I just popped it up. Why did I bring it up again? Look, it fit in. I mean, I was following it. It's in because... Because when you ignore what you're doing, then you're doing things.

[64:39]

Two things are doing things. And because they ignore what they're doing, or they ignore what's happening, I should say, then they think they're doing things. And you ignore what's going on, then you think you're doing things. You think you have consciousness. And you think that there's self and other. And then you think that you're doing this to me. And then I feel pain, and I feel pleasure, and I cling to it, and it wants more of that and less of the other. And then I get into all kinds of creating war situations, setting up war, and then the whole thing starts falling apart. And then I say, oh, shit. I've had enough of it. I'm not even going to breathe anymore. I'm going to die. And then you do that again. And then that causes another birth. And then again, when you're born, you start to say, I'm not going to pay attention to this. And then again, when you don't pay attention, you think, oh, oh, I'm doing stuff. And then that's birth and death, round and round and round.

[65:39]

I'm doing it. I'm doing it. I'm doing it. And here's what I do. That's what people do. That's the cycle of doing. That's karmic cycling. There is this birth and death, round and round, by this mechanical, inexorable cycle. real suffering. And it comes from ignorance, from ignoring your errors. Ignoring your errors. And admitting your errors doesn't mean you stop the error right away, you admit them. Because since you've been making errors for so long, they're well established. So it's not like, okay, I'm going to stop the errors. Because again, stopping the errors is just the same. I'm going to stop thinking that I do stuff. I'm going to do the thing called stopping thinking that I do stuff, which is a source of karma. But again, that's just simply the same thing over again in a newfangled way. The new thing to do is, rather than say, well, I'm going to stop being the way I am, I'm going to start admitting who I am.

[66:43]

That will be a change. That's a revolution. That's the first step in turning the world around and sending it the other way, away from ignorance and birth and death, misery, back towards honesty, awareness, awareness of errors, and awareness of the errors and how they lead to karma and how that causes pain. Awareness of this process turns the process around. It's still birth and death, even in the awareness, right? No, the awareness is not birth and death. There is still causation, but now by noticing the causation of birth and death, that awareness produces the causation of awakening. Awakening is to study the process of birth and death, is to watch how the illusion works. When you understand how the illusion works, then you wake up. to the fact that it actually doesn't work that way, that that never really is true, but because you didn't... The misery is the result of not paying attention, studying the process of existence and non-existence.

[67:58]

And the results are called... One would call the results as misery, another would call it birth and death. To exemplify it, the misery, of course, it doesn't just... It isn't like misery. It's like misery and then it changes into the next kind. It goes through the cycle. So you're willing to keep living. Which is good. But what we'd like to do is live with awareness. And the first step in returning to this perfect, all-embracing, compassionate awareness is to admit that we have this wonderful ability to and to grab extremes. We have a wonderful way to be upgraded to be polluted and to make errors. And there's a power of repentance.

[69:04]

It has power. It has a function. And repentance melts away the power of this river. this karmic rigor, it melts it. It melts all these hindrances and obstructions which are a result of karma. And as it melts it, then you have a chance now to return to your true nature. And then part of that is practices of repentance, which are very much the same as sitting. When many of us sit in sashi again, we're basically repenting, we're admitting all of our understandings of our body. And the way we understand our body and breath and mind is lots of mistakes. And we feel they're a lot of mistakes. They don't feel like the best way to think about our body. They don't feel like the best way to understand our energy. So we watch ourselves misunderstanding our life energy to put it in little boxes or put it in big boxes or put it in, you know, this sphere.

[70:12]

We watch ourselves do this And the more we admit it, the more thoroughly we practice repentance while we're sitting. And as a result of sitting and repenting for seven days, we feel very relaxed sometimes. We feel free, energized, and current. Because at various points during that week, we turned around and went in another direction. We took the backward step, which reverses the world. There's a whole lot of mistakes that aren't on this board, right? You said these were wholesome errors, right? And that there's like sort of unwholesome errors. It's like, you know, like laziness isn't just not setting something up, right? Basically, this is all the errors come from this situation. This is like dualistic thinking here. This is like errors from the point of view of how you relate to Buddha. But I also talked last week about errors in terms of how we relate to subject and object.

[71:16]

I didn't understand the answer. I mean, I don't see how... The errors here are basically the error of a dualistic approach to Buddhism. I'm like, being very pure about practicing Buddhism, or being adapted. As though they were two different things. That's a dualistic approach to Buddhist bodies and being emphasized. And if you take one side of the dualism or the other, then you're caught in a mistake. To not take either side and to watch how they either relate and not grasp either side is not a mistake. However, we do make those mistakes, so we should admit them. Also, in terms of daily life, in a psychological way, I mean, I think either I think I'm you, or I'm not you. And I grasp one of those two. I mean, either I say you're part of me, or I say you're not. Either I say you're my friend, and basically we're kind of like, at least for the foreseeable future, next few minutes anyway, you're my friend, and basically what's good for you is good for me, because I see you as me.

[72:30]

But if I see you as not as me, then I really think you're not. So dualistic thinking in terms of subject-object is the same. You can apply it towards who you look at, towards practice. That's the basic mistake. Basically, there's one fundamental mistake, and that is to believe that there's subject-object, that you're separated from all beings. That's the fundamental mistake, that's the fundamental delusion. It's not a delusion to sort of imagine that something's out there, That's not an illusion. That's just a fantasy. But we believe that fantasy. So if I believe that fantasy and it leads to, let's just say, some kind of like pure self-centered greed or something like that. Or cruelty to some other being because they're not you. Is it necessarily going to be clear that it's in one or the other side of these categories? That kind of... In a sense, it's sort of not practice-related.

[73:32]

Cruelty is not one of these mistakes. Right, okay. You're not... But some people do that. Some people do is they say, I have to do something here for your own good, so I'm going to teach you. And they think that this is the Nirmanakaya Buddha. So then they think that they're making that mistake. In a sense, that's a pretty strict interpretation of how bad this interpretation of Buddha could be. This is self-righteousness. This is the kind of self-righteousness, too, though. This is self-righteousness in the sense that I'm not going to do anything. I'm not going to get involved in worldly affairs in the sense of I'm not going to, like, beat people up for their own good. I'm also not going to tell them, you know, nice things to, you know, get them to practice Buddhism. See, if what I think about... But basically, anyway, getting past 9 o'clock, so... Basically, all errors come from this fundamental dualistic thinking.

[74:32]

They're all ramifications of this basic delusion. You can crank up all the cruelty and stupidity in the world out of this basic thing. It's a wonderful, uh, a wonderful capacity we have. So I, uh... I don't know if we've spent enough time on the refuges, but next time, if you're ready, we can go on to the three pure precepts. And I think I'd like to carry this out to show all these three pure precepts. In the meantime, well, I told enough jokes. Thank you.

[75:21]

@Transcribed_UNK

@Text_v005

@Score_77.51