You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to save favorites and more. more info

Wednesday Event

AI Suggested Keywords:

Wednesday Event

In this talk, the main thesis revolves around the Zen practice of "non-thinking," centering on the dialogue between Yaoshan and a monk about how to think of not thinking, termed as "non-thinking," which is an essential art of Zazen. This practice is discussed in relation to Dogen's teachings and the Bodhisattva path, underscoring the necessity of doctrinal understanding and deep meditation to ultimately embody the Buddha-nature beyond individual thinking. The talk further explores how integrating doctrinal study, contemplation, and meditation leads to a profound understanding of emptiness and the compassionate activity at the heart of the Bodhisattva's practice.

Referenced Texts and Teachings

- Dogen's Instructions on Sitting Meditation: Reviewed as pivotal in understanding the concept of "non-thinking" in Zazen and its role in transcending ordinary thought processes.

- The Samadhinirmocana Sutra: Discussed for its teachings on the deep meditation practice essential for developing a profound and intimate type of wisdom in the Bodhisattva path.

- Four Noble Truths: Used as an example of doctrinal teachings that are fundamental to understanding the nature of suffering and the path to liberation.

- The Concept of Emptiness: Explored in relation to its necessity for developing compassion and the ultimate liberation of beings, where understanding of emptiness intertwines with ethical practices.

Speakers and Dialogues

- Yaoshan’s Interaction with a Monk: Central dialogue illustrating the concept of "thinking of not thinking" and its implications for practice in Zazen.

- Dogen: Cited for reasoning how the process of questioning the practice itself constitutes the essence of "non-thinking" and its import to Zen meditation.

- Audience Interaction: Engages with questions regarding the dichotomy between intellectual study and direct realization, emphasizing the Bodhisattva's journey towards attaining a balance between wisdom and compassion.

AI Suggested Title: Embodied Wisdom Through Non-Thinking

Speaker: Tenshin Reb Anderson

Possible Title: The Path of the Bodhisattva

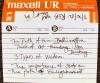

Additional text: Think of Not-thinking: Nonthinking

Speaker: Tenshin Reb Anderson

Possible Title: 3 Types of Wisdom

Additional text: The importance of study on the path of enlightenment

@AI-Vision_v003

Wednesday Event

The path of the Bodhisattva, think of not thinking: non-thinking

Three types of wisdom

The importance of study on the path of enlightenment

Last week I passed out a little summary of the Bodhisattva Path and we read it together. And the week before, I think maybe the week before, I'm not sure, I referred to this kind of standard scriptural presentation of the Bodhisattva Path and mentioned that the practice of the Zen school is, you know, it's said to be a transmission separate from most

[01:02]

scriptures, but I don't think so. So that's why I mentioned the scriptural teachings, I mean, I bring them up. In one of our frequently recited manuals of meditation, we hear the instruction to think of not thinking, and then the question is raised, how do you think of not thinking? And then it says, non-thinking, and then it says, this is the essential art of Zazen,

[02:07]

this is the essential art of sitting meditation, and that instruction arose supposedly from a conversation with an ancestor of the Zen tradition, and that ancestor's name was Yaoshan, and he was sitting once, and a monk came up to him and said, sort of said, what are you thinking, what kind of thinking is going on while you're sitting so still? And he said, thinking of not thinking, and the monk asked him, how do you think of not thinking, and then Yaoshan said, non-thinking. And I remember that Dogen likes this instruction very much, that's why he puts it in his general

[03:15]

instructions on sitting meditation, but also he commented on it, he said, when the ancestor Yaoshan said that the way he was thinking while he was sitting was not thinking, that when the monk said, how do you think of not thinking, Dogen says, that's it. Just to ask, how do you think of not thinking, that's thinking of not thinking. And then again Yaoshan says, non-thinking, in other words, the way you think of not thinking is beyond thinking, so what he's doing, the kind of thinking he's doing when he's sitting is beyond thinking. And again Dogen says, this is the essential art of the sitting meditation of the Buddha

[04:20]

ancestors. And it seems to me that if one was sitting or standing, practicing an art which was beyond thinking, then if there was some thinking going on, that art would not get involved in that thinking, and that art would not try to stop the thinking. And if there was no thinking, that art would not be unemployed, because the type of thinking

[05:28]

is, the type of art it is, is beyond thinking, so whatever thinking is doing doesn't really touch it, and it doesn't touch the thinking. That's what it seems to me. So most of us do spend some time thinking, or in other words, we, most of us experience thinking going on, often. So there's an art that's beyond this thinking that's going on, which isn't separate from it, because that wouldn't be beyond it, it's not identical with it, because that wouldn't be beyond it. It's a kind of, it's an art, I would say, that transcends sameness with the thinking, and difference from the thinking.

[06:28]

It's not completely the same as the thinking, or completely different from the thinking, that's the kind of art it is. So when one, maybe I could say, when you come, for example, into this room and sit down, is there this practice? I won't ask you, are you doing this practice, because you doing the practice is just thinking. But, is that kind of practice happening at your seat? So you may sit down, and while you're in that sitting, there may be thinking going on, or what sometimes people call daydreaming, or fantasizing, or planning, or trying to figure

[07:37]

out what the Bodhisattva way is, or something like that might be going on in your body-mind complex while sitting here, right? And I've heard people say that that sattva-mind does happen. Well, something like it, yes. So the practice of the ancestor, the arsana, seems to be a practice which is kind of beyond that stuff, this kind of thing going on. Now I think it says in that thing something like, put aside blah-de-blah, put aside various worldly activities. But again, I understand there's various ways of understanding it. One way would be, do some thinking, do a special kind of thinking called putting aside a certain kind of thinking. So maybe they mean that, when he says put aside this or that, that's possible.

[08:40]

But after you do that kind of thinking, or before you do that kind of thinking, no, yeah, before you do that kind of thinking, and while you're doing that kind of thinking, and after you do that kind of thinking, still, the essential art has nothing to do with that. The essential art has to do with not being defiled. So you don't defile the essential art of non-thinking with the thinking, and you don't defile it with the lack of the thinking, and you don't defile it by getting some other kind of thinking. So there's a sitting in this art of not defiling the art, of not defiling this being beyond thinking. And, once again, most people's report of their sitting meditation practice is they

[09:48]

report their thinking, and some of them, when they report it, they are basically confessing. They're confessing, I'm thinking this, I'm thinking that, I'm thinking this, I'm thinking that. Those are the people who confess, who are confessing their lack of faith in the essential art of Dzasum. In other words, I sit down, but all I'm doing is being caught up in my thinking. And I might say to the person, well, do you vow to practice the art of being beyond your thinking? Do you vow to realize the practice of being beyond your thinking, which means you vow the practice of you not trying to do anything to be beyond your thinking, and just sitting and appreciating and receiving the Buddha mind, which is beyond your thinking and my thinking? Do you, would you vow, do you vow? Would you like such a practice to be realized at your sitting place?

[10:55]

And if you would, then when you sit down, maybe you could remember that, and just sit down, wishing that the Buddha mind would be realized at your sitting, vowing that it would be realized there, vowing that this essential art, which is beyond thinking, would be realized. So this way of talking is somewhat familiar to some of the people here, and I think it might even be really comfortable for some of the people here, because it's really a nice teaching, isn't it? The teaching about art, which, you know, you don't do, nobody else does it for you, but it's actually, it's the art of how you are with everybody right now, it's the way

[12:01]

you actually are with everybody right now, and the way you are with everybody right now is beyond thinking. So it's kind of a lovely practice, lovely art of just sitting down and appreciating your interdependence with all beings, and appreciating how all beings give you your body and mind each moment, and then by the nature of, then the type of body they give you is a body which only lasts for a moment, and then it changes, or rather, then it ceases. The body that people give you, the body that comes to you each moment by the kindness of all beings, because it comes in a moment, it also leaves in a moment, it's a very rapidly perishable self, that's the one that you get in a moment from everybody. Does that make sense? Who knows, maybe it does. So that one comes and goes, and then it's kind of, can you sit there, or would you vow

[13:06]

to sit there and receive this gift, and then, since it's going anyway, give it away. This is entering into the samadhi of the essential art of zazen. But this samadhi, which is the essential art of zazen, is not the entire extent of the Buddha's mind, it's just like the essential practice, the essential art, it's kind of like the basic requirement, in other words, we have to stop defiling our practice by trying to get something or avoid something. Now the rest of the practice, the rest of zazen, that's the part which you hear about in the description of the self-receiving and self-giving away samadhi, and in that samadhi

[14:15]

they describe the wonderful activity of liberating beings from all the kind of thinking that they're doing. So the essential art of zazen is beyond all this thinking, but at some point this practice needs to reconnect with the thinking to set the people who are thinking free of the thinking, and that's when you actually voluntarily enter into virtuous practices based on or coming from or acting out this non-thinking, and these virtuous practices are for example briefly described in that piece of paper that we recited last week.

[15:17]

And then when people look at the piece of paper and start entering into what's involved in that piece of paper, then you put your non-thinking to a test, in other words, yeah, you are tested to see if you can continue to devote yourself to this essential art of non-thinking while you try on all kinds of thinking, all kinds of learning. Learning all kinds of skills, learning all kinds of teachings so that you can teach them, learning all kinds of practices about how to develop compassion, for example. But the zen presentation, you see the zen teacher sitting and you say, what are you

[16:28]

thinking about? Are you thinking about compassion? Well, he might have been thinking about compassion, but he didn't mention that. He mentioned that he was thinking of not thinking. And so his emphasis to this monk was to tell this monk how to conduct himself or herself such that if she was practicing compassion, she would not just be practicing compassion from the place of her thinking, which is presently probably hooked into all kinds of misconceptions. So first of all, realize non-thinking, then go back and join that non-thinking with thinking about giving, with thinking about the precepts, with thinking about patience, with thinking

[17:31]

about diligence, with thinking about various kinds of concentration practices, and thinking about wisdom and how to develop wisdom. And then, as we get into how to develop wisdom, which is actually involves a lot of thinking, then zen students feel unfamiliar with that territory. But still, I'm sort of like coming back around to bring this up, these different types of wisdom. And so I mentioned last week that one type of wisdom is the wisdom which comes from,

[18:34]

for example, listening to somebody talk to you like this about the essential art of Zazen. So although the Zen school is called a school which is not depending on the doctrinal teachings, this teaching is kind of a doctrinal teaching of the Zen school. Does that make sense? And so then you hear about this teaching and you might have questions about this teaching, and so I've said this teaching in various ways tonight and other times other ways, so you might have questions about this, and you might have questions about where you stand or where you sit vis-a-vis such a practice, and so this kind of thing has to do with learning about this. And then comes another kind of wisdom after that, and that's a part which I think also

[19:40]

is quite unfamiliar to Zen students, so the first type of wisdom I just mentioned is the wisdom of hearing, based on hearing, which is to learn and study teachings, and I just gave an example of one tonight, of a teaching, which you learned maybe to some extent, and as you learned it you were developing some wisdom vis-a-vis this, but the wisdom deepens as you get more and more engaged in it. So there's another aspect, the next aspect of wisdom is the wisdom of pondering or reflecting on such a teaching, of analyzing it, of reasoning about it, and this same two phases of wisdom regarding any teaching are there. Any kind of teaching you could apply these two types of wisdom training.

[20:41]

The second type of wisdom is to train your mind at reasoning, to learn how your mind reasons, and you can use it on a teaching like this, but you can use it on any kind of teaching. Eventually, we want to use this kind of learning, we want to learn about ultimate truth, we want to, the Bodhisattva wants to learn about this. Hear the teachings, get the terms clear, ask the teacher questions and get it clear, then you want to reason about it and analyze about it. And from that kind of actual intellectual activity you come to an understanding of emptiness, an intellectual understanding of emptiness, of ultimate truth.

[21:46]

Now, the essential art of Zazen still applies, it's just that now we're considering practicing non-thinking with a developed understanding of ultimate truth. And then, we enter into, we bring the understanding, for example, of emptiness, or any teaching, into the realm of the actual meditation. And then the understanding of the teaching, by integrating it with the meditation, it's

[22:52]

no longer just intellectual understanding, it is the full-bodied understanding which has no duality between the meditator and the teaching, or the meditator and the teaching of the practice. And then, when you, some people have asked me, if I, you know, would I, would I sitting in the Zendo bring up various doctrines then? And it isn't necessarily that you'd bring them up, but if you had been studying these doctrines, both in terms of studying and reading and discussing, but also pondering and reasoning

[23:54]

and analyzing and investigating these teachings, if you'd been studying a book or walking around thinking about this, and I just want to make a little, kind of a big parenthesis here, and that is, when I was studying in the past certain teachings, certain doctrines of the Buddhist tradition, so there's, you know, there's different schools, different doctrinal schools within Buddhism, as I was studying some of these doctrinal schools, I would read these things and then sometimes I would quit studying them because they were hard or I didn't understand very well, or, well, for various reasons that one might have for stopping studying

[24:57]

something, and then somehow, I don't know, it happened at some point, for some reason, I was offered the opportunity to teach classes, and for some reason or other I started teaching classes on the very things which I found most difficult, and then they got even more difficult, because as I studied, I started asking questions that I thought someone might ask me. I would read this, you know, you read and say, okay, okay, but what if somebody asked, what's that, or what does that mean? Then the study slows down and it gets deeper, because you try to analyze and reason with this question that comes up in your mind, because you're going to be teaching this. Now, you'll probably never get asked all the questions that you would think of actually, but still, when you know you're going to

[25:58]

be having this situation of teaching a text, you go much deeper, you probably will go much deeper. And of course, for a Bodhisattva, the reason for studying these texts is, you know, for two reasons. One is to attain unsurpassed enlightenment yourself, but also to be able to teach them. But thinking about teaching everything you study, you naturally start pondering. Now, you could be talking to someone about what you're going to teach, but then that's back in the realm of learning phase, or through the hearing. When you're actually using your own mind and your own experience to test the teaching that you're learning, you develop the deepest intellectual understanding under those circumstances. Closed parentheses on the advantage of teaching, or the advantage of wanting to teach a text,

[27:01]

rather than just read it for yourself. Also, when you're teaching, you might keep studying something that you otherwise would give up on, because you know you've got to go to class. Now, you can go to class and say, I gave up. That sometimes is quite encouraging. And that makes the teaching go deeper, too. That you went there and said, I gave up on this text. It was so hard for me. And then all the students say, oh, come on, try harder. Go back, give it another try. What's the problem? What problems did you have? What places were you having trouble? I say, well, when I thought of you asking me the following questions, and they say, what were the questions? And then you tell them the questions, and say, those are good questions. Well, what's the answer? And so on. So the meditation practice of the traditional presentation of the path to Buddhahood, the meditation practice, which develops the deepest

[28:05]

kind of wisdom following these two previous kinds of wisdom, the wisdom of study and the wisdom of pondering and investigation and analysis, the third kind of wisdom based on meditation, when that teaching is presented, like in one of these sutras called the Sutra of Elucidating the Deep Mystery, the Samadhinirmocana Sutra, the Bodhisattva love, the Bodhisattva Maitreya, asks Buddha, sort of, based on what, or abiding in what and relying on what, does the Bodhisattva do the meditation practices to develop the third and deepest kind of wisdom? And the Buddha said, abiding in and depending upon an unwavering resolution to teach the

[29:08]

doctrinal teachings and to attain unsurpassed enlightenment. That's what the Bodhisattva abides in and relies on, an unwavering resolution to be able to teach the teachings and not fall away from unsurpassable enlightenment. That's the basis of practicing the meditation, which develops the third kind of wisdom, the deepest and most intimate type of wisdom. But that type of wisdom depends on that you have some understanding which didn't come through meditation. So we are not able to understand the teaching of selflessness of persons and selflessness of all things. And we're not able to understand the Buddha's teaching about what the ultimate truth is, the ultimate truth which when we are directly

[30:12]

knowing it and intimate with it, is the real antidote to all suffering. All the other antidotes are short term. The real antidote is the ultimate truth. But in order to directly realize that ultimate truth, we have to have heard the teaching of the ultimate truth. For example, we have to hear things like, well, the ultimate truth is not, it transcends being the same as you're thinking or different from your thinking. You hear that teaching. So when you're sitting, you can tell whether you're looking at the ultimate or not, because the ultimate would be, it wouldn't be the same as what you're thinking and it wouldn't be different. Well, where is it? Well, what's more teaching about it? Well, yes. Then you get more teaching and then you analyze that teaching and then you understand, you intellectually understand, you understand the ultimate truth by studying it, by studying the teachings of it. Then

[31:22]

in order to be able to really teach this rather than just understand it intellectually, to teach it from your guts and also to attain unsurpassed Bodhi, then you take this understanding of, for example, ultimate truth, but anything, into the Samadhi. Now, all the Zen teachings, I feel, when you start, when you understand those teachings and you bring them into your Samadhi, then those teachings help you go back and learn all the teachings which help you understand the ultimate truth and bring that into your Samadhi. But this is something which I'm finding is daunting for us. So I'm going around and around again about this and and it's now eight, a little after eight, and I see a hand. Yes?

[32:35]

I have a question. You said that you need to study ultimate truth intellectually before you can realize it, but you said in another lecture that the Buddha is the Buddha and not a Buddha because he discovered the ultimate truth by himself without having heard it. Let's see, now, you said I just said that you have to study an intellectual truth before you can before you can what with it? Realize it. That's at least how I understood what you were saying. Well, the deepest kind of wisdom about any topic will be based on practicing stabilization and insight. And when you practice insight, you actually look at something. Okay? But if you don't have an understanding to look at,

[33:37]

if you have no insight, no understanding of the object to look at... You can look at your experience as an object. Isn't that what the Buddha did? Yeah, but if you don't understand your experience, if you don't have any... if you don't understand the way you have the experience, then it would be very difficult for you to realize what your experience is. So, for example, pardon? But, like, how did the Buddha understand it? Didn't he just look at it and study it and then understand it? Well, the Buddha is the one who taught this stuff I'm telling you about. So he did it the way I'm talking about rather than the way it sounds like he did. So they were teaching, they were telling them, like... The Buddha, you know, he said that he practiced with other Buddhas before he was like the Bodhisattva in this world. He practiced with other Buddhas quite thoroughly and got lots of

[34:43]

teachings there and got predicted to be Shakyamuni Buddha. So he learned all these teachings from other Buddhas before and rediscovered them in this world. But when you look at something, in fact, when you look at an object, in fact, you have some kind of like... what do you call it? What's it called? It's called... you have a doctrine. Okay, that's good then. You have a doctrine. But our doctrines, the doctrine that we usually have about what we look at, which we're not aware that we have, but the doctrine we usually have, most people have, is called naive realism. That's the doctrine which most people innately have. We just... it comes right along with our body and mind. That we think that what appears to us is actually the way the thing is.

[35:47]

This is our doctrine. And if you have not understood that that's your doctrine, then when you look at something and think based on that doctrine that it is the way you think it is, then this is not called insight. Now, if you're calm and then you look at things in that calm, then you'll be calm with this lack of insight. You know, you'll be calm with basically believing your naive realism. So, for example, I may think you are I don't know what, you know, but I think you're something, you appear as something to me. And then I naturally, naively think that what I see there is actually what's there. That there's something actually out there separate and independent from what I think about it. This is what people normally think. That, you know, like this person is, the way she is,

[36:53]

is independent of my thoughts about her or, you know, my thinking about her. And also, then even going farther than that, you could say, that's naivety realism. That the thing that you see is actually out there on its own and it is the way you think about it. Now, you could also make a little bit more sophisticated and say, well, it's not actually exactly what you think, but it is out there independent of your thinking. That's more developed realism. If you don't know, if you haven't examined the teachings about your own mind and about other people's minds, and you look at these objects when you're calm, then if you think somebody is your enemy and you don't think that that enemy status

[37:55]

really has much to do with your thoughts, but actually that they actually are independent of your thoughts and a thing called an enemy, if you actually think that and you're calm, you'll be cool. You just sit there, you know, like, well, this is my enemy, but I'm cool. So, just practicing calm by itself prevents you from the affliction which comes from misconceptions about what other people are, while you're calm. Now, as soon as the calm goes away, if you stop doing the calming practice, then you're just like sitting there and then you're assailed by the affliction of your belief in what you are perceiving. But if you have teachings which help you identify where you stand in terms of how you see things, and you can find out that you're a such-and-such type of philosopher, then you can have some insight based on understanding the teachings which you've

[39:00]

gotten about the way you see things, and then whatever you look at, you can have understanding, and then you can go deeper and deeper by hearing of deeper and deeper understandings of how you do contribute to the world that you are experiencing. So, the Bodhisattva path is a path where we are bringing out teachings that either Shakyamuni didn't give because he didn't think people were ready for them, or he gave them but they didn't hear them, or he gave them but they forgot. So, and I said at the beginning of presenting this Bodhisattva path that in the early

[40:01]

presentation of the teaching, in the early collections of the Buddhist teachings, you do hear about, for example, the four Brahma-viharas, which are love, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity. You hear about these. But these practices are generally represented as antidotes to anger, and they also develop calm. Now, they're not usually used as calming practices, but they actually can develop calm. They're mostly offered as preliminary antidotes to the meditation practice. But in the Mahayana, those two first points there of love and compassion are the main point. So, the Buddha, did the Buddha give those teachings, or did the later students of the

[41:17]

Well, he did give those teachings. He gave those teachings of the four Brahma-viharas, and we're just going to take those first two, and we're going to say those first two that the Buddha gave as one of the many teachings he gave, those two were really the core, the center of all of his teachings. And the other, the early people didn't point that out. They did notice that the Buddha said this, so they're not going to say that we're making this up, this thing about love and compassion. They're not going to say, you're crazy, Buddha never said anything about love and compassion. No, he did say something about it, but not much. And these people say, well, not much, but he just happened to feel that that was the most crucial and fundamental issue of the whole point. Okay, so I'm bringing this up because the Mahayana is an interpretation of what was most important for the Buddha.

[42:18]

And so you study that teaching, and you change when you have a different understanding of that teaching. Yes? My question is exactly what you just said, but I wonder why love and compassion are the most important teachings. And I guess I thought of this question because the Buddha some days said very clearly that emptiness is not definitive proof. The only definitive proof is emptiness. So then I thought, so then what are our vows? Is that just sort of, okay, given emptiness, we're going to decide to live with love and compassion? And that makes sense? Well, it's more like, it's more like, given compassion, you want to realize emptiness so that you will be able to help all beings be happy.

[43:32]

In other words, you realize emptiness will help you realize your love for beings, your wish that you would be able to actually intensely help them be happy, and that you would be able to actually help them be free of suffering. You want that, that's the basis. It's because of that that you want to understand emptiness, because you understand that emptiness is what makes that really possible, because in order to really help people be free of suffering and be happy, they need to understand emptiness. So you're going to learn this so you can teach it to them, because everything else is short of that real cure of suffering, emptiness. So emptiness is the definitive truth. It's the definitive truth for liberating beings, but it's based on compassion that you're willing to do the work,

[44:34]

the joyful work, of developing a closely watched relationship with emptiness. Could that be a way to go with emptiness? Yeah. So that's part of the teachings, is to help you understand that emptiness does not mean nihilism, so that nothing matters. There's nothing anyway, so it doesn't matter whether I practice the precept, it doesn't matter whether I teach people emptiness. Because of emptiness, it doesn't matter if I teach people emptiness. Now, because of realizing emptiness, you can really teach people what you want to teach them. Your compassion can really work now, because you understand the most important thing to teach

[45:41]

people. But you also understand many lesser things to teach people, which you learned on your way to understanding emptiness. You had to practice lots of compassion, you had to learn how to calm down, you had to hear the teachings, you had to analyze them, you had to understand them, you had to meditate on them, you had to become intimate with them, so that you could understand emptiness. And now you did all that, and you made all that effort, because you didn't, you weren't lackadaisical, you didn't have despair of nihilism. And the teaching, the teachings helped you become free of your misconceptions, your various layers of misconceptions helped you become free of them, so you could see emptiness. But it also protected understanding emptiness, once you became free of your earlier misconceptions. So that's another reason why almost nobody, well anyway, yeah I guess almost nobody can like approach emptiness without some kind of like warnings and protection about misunderstanding it. It's a very dangerous

[46:42]

teaching, that's why we have to have all this other conventional teachings to protect ourselves from misusing it. And the whole process of learning all this needs to be, we need to abide in an unshakable wish to teach people, and wish to attain enlightenment in order to teach them. But otherwise just hearing about emptiness without basing it on compassion, and also having lots of teachings to warn us about misconceptions about it, we could get in big trouble. And but we're not really at the trouble of emptiness yet, we're mostly just like working, we're just talking about the Zen approach, which I feel like teaches us how to approach the Bodhisattva practice properly. It teaches us the right approach to the development of all the equipment that we need to realize the ultimate truth for the welfare of all beings.

[47:46]

And I think that Zen is very good that way of keeping the meditation pure. And in some ways some of the questions people have about this traditional or the scriptural presentation of the Bodhisattva path, some of the questions people have are because they imagine approaching these teachings in an inappropriate way, and they think that's what they're being told to do, but they've practiced meditation long enough to know that that approach might not be appropriate under a meditative context, and they're right. So once again someone said, would you bring up these doctrines in meditation? And again as I was saying, if you are, that was where the parentheses started, if you are like thinking about things all the time because you're

[48:48]

going to teach them, then when you sit down on your cushion to meditate, the kind of thinking that's going on, instead of being planning, I don't know what, you're planning your class. Instead of worrying about, I don't know what, you're worried about your understanding of various doctrines, or you're worried about not even understanding what your understanding is of your doctrines. So when you're involved in, if you're a carpenter, when you sit down to meditate, it's very likely that thoughts of carpentry will arise. If you're a mother, it's very likely that thoughts of your children will arise. If you're a lover, very likely thoughts of your lover will arise. If you're a hater, thoughts of who you hate will arise. So we tend to have some continuation

[49:50]

of our habitual line of thought seems to go on when we sit down, right? And sometimes we're so busy and running around in our daily life that we don't even notice when we're running around what thoughts are going on. And when we sit down in meditation, so-called meditation, in other words, we sit down, then we realize what's been going on all day. We realize what, you know, what it was like all day long, but we were running so fast we didn't notice it. Now, if what you're doing is studying, for example, the structure of the Bodhisattva path, and you're doing that intensively, either at the learning level or at the examination level, it's fairly likely that such thoughts will arise while you're sitting. Does that make sense? So I'm not telling you that if you're trying to learn this course and learn how to do these

[50:51]

different types of wisdom practices, that you should go into the Zen-do and go sit down and then bring this stuff up. I wouldn't suggest that, actually. But I might suggest, not even suggest, but I might say, we're having a class, and in this class we're going to study the three kinds of wisdom, and you can come if you want to, and we will be discussing these in class, these three types of wisdom, if you want to come. And then, after you learn them, then I might say, okay, you get certificates, little wisdom certificates of learning about the first kind of wisdom and the second kind of wisdom and the third kind of wisdom. Now, you learned about them, but you only realized the first one. Now, if you want to realize the second one, you're going to have to ponder this outside of class. Now, if you don't want to, you don't have to, but there's this opportunity. Then you ponder it outside of class, intensely, thoroughly. You start to understand whatever the teachings

[51:54]

are. And again, somebody said, well, can't you just study what comes up? Yes, you can study what comes up. But what comes up is actually, you will see, is this the meaning or the objects that the teachings told you about? I don't know if you get that, but that's a big, maybe I'll talk about that next week. Basically, what you're meditating on when you're doing wisdom work is you're meditating on the teachings and the meanings of the teachings, or the teachings and the objects which the teachings are talking about. So you're directly hearing about how to analyze experience into the five aggregates. You're learning that teaching and you're talking about that teaching and you're pondering that teaching until you understand what that means and how you would do that teaching and how you would apply that to looking at your experience. And then the other

[52:56]

side of the insight work and wisdom work is actually looking and seeing what you learned about, or the Four Noble Truths. You learn the Four Noble Truths and then you look at your life and you see the Four Noble Truths, or at least you see the first two. And so on, you know. Or you just see one, right? Yeah, you only see one. And you can see the other one quite soon if you'd like. Okay, which one do you see? You see the Nirvana one? Which one do you see? Come on, tell us. I'm just very beginning. I know, which one do you see? No, no, no. Four Noble Truths. Which of the Four Noble Truths do you see? Compassion. Suffering. I see suffering. I feel suffering. The Four Noble Truths, did you know what they were before we brought this up?

[53:58]

Did you? Sometimes I do. Well, what are they? Am I being gentle? Well, I'm trying to find out if you've heard of the Four Noble Truths, and then if you really mean that you're only doing one. Because if you're only doing one, I could easily get you to number two right now. But maybe you don't want to do this anymore, is that right? Okay. So anyway, the Four Noble Truths is another example of a teaching, and when you hear the teaching then you say, okay, the truth of suffering, the truth of the origin of suffering, the truth of the end of suffering, and the path to realizing the end of suffering. Okay, now where do I stand on that? You analyze this. You think, well, well, can I find some suffering? You talk about it, and so on. And then you can also start investigating and reasoning about this process and see if it's reasonable. Maybe you say,

[54:58]

this Four Noble Truths actually doesn't make sense. Maybe you can work on that. But that's just one example of something you might be working on. So then you sit in meditation and this stuff comes up. And if you have a good understanding of the teaching and your understanding has arisen from investigation, that understanding will just arise at some time when you're sitting, just like your understanding of other things will. But now it's going to be in the context, perhaps, of practicing the essential art of zazen, of non-thinking. And then you can again look in that context at what you understood and it goes deeper. And then you have a deeper understanding of whatever the teaching was, including the teaching of the four of the essential art of zazen. So you don't have to

[56:02]

bring this stuff up in your meditation, and it won't come up if you never hear about it. There's all kinds of teachings which are probably never going to come up in your zazen until you hear about them. And even after you hear about them, they won't necessarily come up much. But if you hear about them a lot, they're more likely to come up. And then if you analyze and investigate them, then the wisdom that comes through the analyzation analysis will come up. And if it comes up in calm, then you're going to develop a third kind of wisdom. But all this could happen without you directing your mind any place because you actually might be practicing not directing your mind anywhere. You might be just practicing sitting as Buddha. And then sitting as Buddha, but you happen to be Buddha who is in the Bodhisattva training course. So you actually have Buddha mind there, but Buddha mind is now just going to get put through this

[57:03]

Bodhisattva training course to become Buddha. So you have Buddha mind which is just non-thinking. But you haven't yet attained Buddhahood. Now you're going to take this non-thinking Bodhisattva through this course to Buddhahood and you're going to learn all the teachings and you're going to finally learn the ultimate truth. And then you're also going to learn how to bring that truth together with all the practices which you learn how to do. And you're going to do more and more of these virtue practices, all of this done with non-thinking. You're going to practice giving with non-thinking. In other words, you're going to practice giving beyond your thinking about giving, right while you're practicing giving. And you're going to practice non-thinking while you're studying scriptures. Right in the middle of the study you're going to be practicing non-thinking. So it's going to be Buddha going to Buddhist school.

[58:06]

So it's going to be Buddha who's not trying to gain anything, but happily learning all these teachings so that she can teach all these teachings. And learning all these meanings so she can share these meanings. So please keep rectifying the practice while you hear about these other practices and these other teachings. Don't be caught by anything, by any of these doctrines. And if the word doctrine also means dogma, okay, so you could say the bodhisattva is going to teach all the dogmas. The bodhisattva vows, what is it? Dharma gates are boundless. In other words, the dogmas are the dharma gates, or the dogmas are the gates through which the dharma comes. And I'm going to learn all those dogmas, but they're going to be gates. They're not going to be something I

[59:12]

hold on to. Bodhisattvas make such vows. You've heard of them, right? I'm going to learn all these dharma gates. I'm going to learn all these teachings. That's what it says. The dharma teachings, gates are teachings, dharma teachings are endless. I'm going to master them all. I'm going to learn them all. Now you may want to skip that line for a while, but that's what we've been saying, that we're going to do that. That's why we need non-thinking, because with non-thinking we have the energy, the Buddha energy, the pure approach, the non-linking approach to this enormous field of virtue, of learning. Yes? So, would you say that what this teaching is, is actually the teaching of right understanding,

[60:21]

right view? Is what teaching the teaching of right? All of this that you've been talking about. Are we talking about mastering right view? We're talking about, well part of the teaching is compassion, okay? And then another part of the teaching is teaching about the actual aspiration to become Buddha. Now in order to become Buddha, you need not only compassion, but you need right view. So right view is the wisdom that the Buddha has, but the Buddha is not just a wisdom person. The Buddha is a compassionate person. So the Buddha has tremendous, what do you call it, tremendous, I hate to use the word, but anyway, tremendous storehouse of virtue and merit from doing all kinds of compassionate activity, and that's joined with

[61:29]

right view. So we need to work on both. We need to join the compassionate, skillful means with the right view. And again, the Zen approach is, we have this huge field of virtuous practices which we bodhisattvas want to enter, and we also have this very subtle wisdom teaching which we want to master, and we want to join these two perfectly, so that all the virtues can really flourish completely with no hindrance and no impurity due to lack of understanding, and the wisdom can really come alive and work for people's benefit. We want them completely integrated, and we want to approach this huge project with this no grasping and no seeking, so that we'll be most effective in walking this path, so we can be most resolute

[62:31]

in saying, you know, I haven't learned very much, like Dogen said, you know, I haven't learned too much so far. There are 10 million things about Buddhadharma I don't yet understand, but I do have the extreme joy of right faith. In other words, right faith is faith that it's Buddha that's practicing, and there's no hurry, and we're just going to just roll this big Buddha vehicle forward, little by little, each moment, all together, you know, and we're going to just do all these practices when it's time to do them. So otherwise we get a little too excited or depressed about the huge project of becoming a Buddha, the Bodhisattvas do. So that's why I think Zen has a point, but the Zen people

[63:34]

shouldn't forget about what it takes to make a Buddha, but at the same time they shouldn't remember and get totally hysterical and then say, you know, well I give up then, I'm just going to be, you know, I don't know what, a miserable, lousy, selfish troublemaker, because that's what I already am, that's easy. This whole process seems to me includes shifting your paradigm. Yeah, the whole process includes it. It's a major shift of your own truth, whether it be good or not good, based on Buddha's point of view. When you say whether it's good or not good, I missed that part. You mentioned hatred, you mentioned love, habitual thinking, so that's the intention of a being,

[64:41]

right? Or the truth of a being? And this process of wisdom and meditation includes this shift from your own truth, basically, into a new truth? Yeah, we switch from our truth, which is usually some kind of misconception, to a correct conception. So you give up your own truth? You give up your own truth, yeah. And then you move on to another one, and then you give that one up and move on to another one, and you keep getting more and more... And how do you do it without seeking? How do you do it without seeking? Yeah. Non-thinking. That's why we have this non-thinking practice, so we can do this without seeking. So we can climb up the stairs up to the sky without any seeking,

[65:44]

but just kind of take a step because it's more like an escalator. It just carries us up without a second. Well, you're still walking, but you're not seeking anything. You're walking, but not seeking. You want something. You want Buddha's wisdom, but you're not seeking. Because Buddha's not seeking, and you're doing the practice of a Buddhist. So we say to Buddha, Hey, Buddha, what are you thinking about? He says, non-thinking. So you can do the same practice as Buddha, called non-thinking. In other words, if there's thinking going on, like seeking thinking, okay, fine. That's not what the Buddha's doing. But the Buddha's also not eliminating the seeking. Have you noticed Buddha hasn't eliminated the seeking? The Buddha allows seeking beings to be even in Buddhist centers.

[66:50]

How do you want something without seeking? Like, for example, you could want me to be enlightened without you seeking my enlightenment. Can't you? I mean, can you? Well, I can want your enlightenment without seeking your enlightenment. I'm able to do that. I can wish things for people and want things for people without any seeking. And that means that if you wish for me to be completely enlightened, and I act not so enlightened, you still wish I would kind of get with that program, but you love me in my lousy, slow progress. You love me in my non-progress and you wish that I would make some progress, but you do

[67:59]

not seek it. And therefore, you can appreciate me the way I am and be devoted to me rather than who I'm supposed to be. And also, if I'm not who I'm supposed to be, you will not throw me in the garbage heap and go find a better person to work with. Unless what you wish is that I was in a garbage heap. Then if you wish that, then I guess, you know, that would be different. But if you wish good things for me and they haven't been attained, you can keep wishing them. And the more you wish with no seeking, you're not attached, right? And the more you wish with no seeking... The more you wish, well, it depends on what kind of wishing. But the more you wish good things without seeking, the stronger the wish. But isn't it trickier when we wish something for ourselves? Isn't it trickier when you wish something for yourself?

[69:03]

It's very tricky when you wish something for yourself. So the bodhisattvas are not too much into wishing things for themselves. They do not wish themselves Buddhahood so much. They vow to realize it. And also, the bodhisattvas, when they get into the program, they're not too concerned about their own enlightenment. They're mainly concerned, really, really, really concerned about other people's enlightenment. So it really is a lot easier to wish good things for Dhani with no seeking than it is to wish it for yourself. So please wish good things for Dhani. That would be not so difficult to not seek anything there. So that's what we do. We wish for others first. That's not so tricky.

[70:06]

It's still a little bit tricky because we can get in there and screw that up a little bit too. That's why we need to wish for others' welfare with no seeking. Because we can still seek, you know, and that shows up because if they don't get where we wish them to be, we get angry at them. We start hating them. We stop visiting them in the hospital because they're not doing their exercises. They're not taking their medicine. They're lousy patients. So we stop going. So we abandon them because we were seeking. We don't want to do that, do we? So we don't have seeking. In other words, we practice, we visit with non-thinking. But, you know, it is tricky. Non-thinking is an art. It's not so easy to learn. But that's how Zen connects to the Bodhisattva path, through the non-thinking.

[71:07]

So Yashan just, you know, he practiced non-thinking. Yeah, did you notice he said he practiced non-thinking? Right? That's the kind of thing. But actually, he also talked to that monk, didn't he? Yeah. And he helped that monk. And he helped Dogen. And he helped you. And he helped me. So he was just practicing non-thinking. But he was like, words were coming out of his mouth, which have had quite a good influence on this world. So he actually was teaching. He wasn't just non-thinking. His non-thinking allowed this wonderful teaching. So as we say, although it's not fabricated, it's not without speech. So non-thinking is not fabricated, but it talks. It speaks English, Chinese, etc. But it's tricky. And it's getting a little on the, it's getting on now.

[72:09]

So we probably should stop. Okay? Is that all right? May our intention equally penetrate every being and place.

[72:27]

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ