You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to save favorites and more. more info

Embrace the Suchness in Life

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk explores the Zen teaching of suchness, emphasizing the inherent completeness and brilliance of the Dharma, free from human conceptions, yet urging individuals to take care of it. It discusses the metaphor of "just this person" as representative of the complete truth and recounts Dungshan’s revelation through the Precious Mirror Samadhi. Additionally, the session highlights the importance of integrating daily life with deep spiritual practice, drawing on Dogen's instruction to Gikai and the notion of a "grandmotherly heart" in practice.

Referenced Texts and Teachings:

- Precious Mirror Samadhi by Dungshan

-

Discusses the transmission of suchness from Buddha to Buddha, emphasizing the need to take care of this teaching as a form of practice and enlightenment.

-

Dogen's Instructions to Tetsu Gikai

-

Describes the importance of internalizing the teachings that the practice of monastic tasks itself is the Buddha way and critical admonitions regarding the 'grandmotherly heart.'

-

Martin Luther's “Awakening” Story

- Provides an anecdote comparing religious realization to everyday actions, illustrating enlightenment in ordinary life.

Referenced Individuals:

- Dogen (Buddhist Ancestor)

-

Integral to the discussion of how individual practice and transmitted Dharma are one and the same, highlighting the concept of suchness.

-

Tetsu Gikai

-

A key disciple of Dogen, reflecting on the understanding of the Dharma and the need for developing compassionate engagement, termed 'grandmotherly heart.'

-

Koun Ejo

- Successor to Dogen and a pivotal figure in maintaining the continuity of his teachings at Eheiji.

The session also reflects on the broader context of Zen practice, underscoring the absence of spiritual reality separate from the practitioner's efforts and the engagement with everyday tasks as a vehicle for transmitting the inconceivable Dharma.

AI Suggested Title: Embrace the Suchness in Life

Side: A

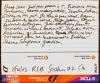

Speaker: Richard Baker

Possible Title: Sesshin #2

Additional text: Dung-shan: Just this person is it, Rereons nmon Sanbaddie, Glory seeking outside, Martin Buber, Sitting in the pot. Be true to your school, Dogen, Salvation by faith alone, Ken, John. Dogens last words to Keizan. Grandmotherly Heart. Monastic rituals & conduct, Suzuki Roshi. Disfunction of Sanboka, Grave Bulk, asleep. Not apart from the luminous Buddha dharma, sunflowers, grandson.

@AI-Vision_v003

this morning I thought I come to take care of what is already complete. The the Dharma is already complete and perfect. And yet, we come here to take care of it. the inconceivable Dharma is the truth that's free of our conceptions.

[01:52]

Those who understand the Dharma or understand the truth that's free of our conceptions. Use conceptions to make designations to tell us about the Dharma that's free of our conceptions. The way we are right now that is thoroughly established, the way we are right now and the way we always will be, is that the way we are is always free of our ideas about the way we are.

[03:10]

And the way we are is that we have ideas about the way we are. But we are free of these ideas all the time. And everything else is too. This is our suchness. Bodhisattvas pay attention to this suchness. And paying attention to this way we are all the time, we evolve and become Buddhas.

[04:23]

The teaching of suchness has been intimately conveyed from Buddhas to Buddhas. It is being transmitted from Buddhas to Buddhas. Now you have it. It is complete, but the ancestors ask you to take care of it. Now you have it and you always have had it, and yet the ancestors ask you to take care of it. An ancestor named Dungshan wrote a poem called, in English, Precious Mirror Samadhi, which starts out saying that the teaching of suchness has been intimately conveyed from Buddha to Buddha

[06:32]

ancestor to ancestor. Now you have it. Please take care of it. Taking care of this teaching of suchness is the precious Mira Samadhi. to be one-pointed, to be wholehearted about taking care of suchness. is the samadhi.

[07:42]

When Dungsan was leaving his teacher, he asked, many years from now, if someone asked me, what was your Dharma? What was your teaching? What should I say? And his teacher said, just this person is it. Then Dungshan left and walked the long time. For years I heard this story, and I used to think he walked down the hill from his teacher's temple, and he got to a little river, and as he was crossing the river, he saw his reflection in the water.

[09:30]

and he woke up. And when I went to China, I went to this river where he saw his reflection. And I asked a Chinese scholar who was with us how far it was from this point in the river to where his teacher's temple was. And he said it's about 150 miles. So he walked a long time before he got to this river, thinking about this instruction. Just this person is it. Thinking about this instruction is the precious mirror samadhi.

[10:36]

And then he saw in the river his reflection. and understood and said, earnestly avoid seeking outside lest it recede far from you. Now I walk alone, but it is always with me. It is no other than myself, and now I am not it.

[11:49]

Only when we understand this way do we accord with suchness. Then he wrote The Precious Mirror Samadhi. all the Buddhas together are transmitting this teaching of suchness.

[13:09]

in order to accord with this teaching of suchness, one has to avoid seeking outside. Or if one seeks outside, One can confess it. Confess that there is a lack of faith in the instructions to not seek outside. And confess that there is some trust in the teaching. Seek outside. get it someplace else.

[14:44]

It's not you. It's apart from this. It's not just this person. This is our teaching we believe in. According to This school, that's a false view. A view leading to unhappiness. The view that there's some truth apart from this person. There is the truth that when you think that there is a truth apart from this person, there is the truth that that's unhappiness. But that's not apart from this unhappy person who believes that.

[15:50]

In this sasheen we have a person who is a descendant of the tutor to Martin Luther, and I sometimes think of Martin Luther, or rather, the thought of Martin Luther sometimes crosses my mind. And one of the main things I think about Martin Luther was that he was awakened, I heard, sitting on the pot. I don't know how much time he spent there, but I heard that's where he had the big breakthrough. In a similar situation recently, I looked at a magazine.

[18:02]

It was a catalog, a Lands End catalog, and on top of the catalog it said, Inside, colon, be true to your school. in the school of Dogen, it looks like there is no

[19:07]

spiritual principle apart from the practice of just this person. And also the practice is not the practice of just this person in the sense of just this person by herself. It is the practice of all the Buddhas together transmitting the inconceivable Dharma, and this inconceivable Dharma is not apart from this person. The instruction, just this person is it, means it's not separate from this person, and it's not this person. It's free of all conceptions, including this person, and it's not apart from this person.

[20:27]

The way this person really is is called the inconceivable Dharma. The way you are is the wondrous Dharma. You've always had it. You have it now. Please take care of it. Taking care of it is the precious mirror samadhi. The Buddha Dharma is sometimes spoken of in such magnificent language or a language about such magnificence that one tends to think there must be something beyond this person, this poor little ordinary person.

[21:34]

But there isn't something beyond this poor little ordinary person. and this poor little ordinary person is not it. And the Buddhas are transmitting the inconceivable Dharma to Buddhas right now. And Buddhas who transmit are seeing each of us as fully possessing the wisdom and virtues of the Buddha. Part of the story one could tell about this emphasis on there being no spiritual reality apart from the person practicing is that

[23:12]

During the time that the Zen teacher Dogen lived, the Buddhist ancestor Dogen lived, during that time there was another school which was called the Daruma school and it looks like some of the people in that school thought that just by faith alone you could realize salvation. By just trusting in the vast, inconceivable, infinite Buddha nature, then everything would be okay, and that whatever you did would be included in the Buddha way.

[24:29]

Of course, Buddha nature does characterize everything, but the Buddha way is not apart from the practice of the Buddha way. And the practice of the Buddha way is that this person whatever this person is at this time, whatever this person is doing, or whatever activity there is of this person, that this person's present activity is the Buddha way. Without that practice, it's not the Buddha way.

[25:37]

there is a subtle distinction between everything being Buddhism and making everything you do an offering to Buddhism. There's a subtle distinction between everything you do is the Buddha way and making everything you do the practice of the Buddha way. Seeing everything you do as the practice of the Buddha way. Seeing everything you do as practice for the Buddha way. So some people, important people at the time of Dogen, seem to have thought, as they say, the mere lifting of the arm or lifting of the leg embodied the Buddha way.

[27:03]

And the other way to put it is the mere moving of the leg or lifting of the arm within one's Buddha conduct is the Buddha way. One side is whatever I do is okay as long as I believe in Buddha. The other is this lifting of this paper is the Buddha way. I lift this paper for all the Buddhas. I lift this paper to manifest the transmission of all the Buddhas.

[28:19]

I'm going here for the Buddha way, rather than I go here and it's the Buddha way. At the time that Dogen lived, he had a number of students who came to him who had a background of believing in salvation by faith alone.

[31:43]

And his teaching was somewhat a response to these people And some of these people lived on after Dogen died and had continued to influence the school he set up, which was in some sense threatened by its own disciples. who misunderstood their teacher. And one prime example of this is one of the ancestors whose name we say in our morning service, Tetsu Gikai Dayosho. So we say, Eihei Dogen Dayosho, Kouhun Eijo Dayosho, Tetsu Gikai Dayosho.

[32:54]

Keizan Jokin Daiyosho. Tetsugikai was Keizan's teacher. I think he was about 20 years younger than Dogen. So when Dogen died, he was about 30 to 33. But even by that time, he had already become a leader of the monastic community. Now, this year, we remember that it has been 750 years since Dogen died. Apparently he died on August 28th, 1253, which doesn't quite make 750 somehow.

[34:10]

But maybe you, maybe you count differently in China and Japan, but anyway, We're going to have the 750th ceremony this year. And in the summer, on July 8th, Gikai heard that his teacher, Dogen, was getting sicker. He had been sick for some time, but that his disease had come back strongly. So he was very alarmed and went to see him. Gikai went to see Dogen. Zen Master, future Zen Master, Gikai went to see Zen Master Dogen.

[35:24]

And Dogen said to him, come close to me. And Gikai said, I approached his right side and he said, I believe that my current life is coming to an end with this sickness. In spite of everyone's care, I am receiving. Don't be alarmed by this. Human life is limited and we should not be overwhelmed by illness. Even though there are 10 million things, I have not yet clarified concerning the Buddhadharma, the inconceivable Buddhadharma. Still, I have the extreme joy of not having formed mistaken views and having genuinely maintained correct faith in the true Dharma.

[36:40]

The essentials of all this are not any different from what I've spoken of every day." If I may comment, he did not form the mistaken view that there's any Buddhadharma apart from the practice. I think that's part of what he was trying to tell Tetsugikai. It's a joy to not have the view that there's some inconceivably wonderful Buddhadharma apart from the practice of this person.

[37:45]

or put it, it's a joy to understand that this practice is not apart from it. This monastery is an excellent place. We may be attached to it, But we should live in accord with the temporal and worldly conditions. In the Buddha Dharma, any place is an excellent place for practice. When the nation is peaceful, the monastery supporters live in peace. When the supporters are peaceful, the monastery will be certainly at ease. You, Gikai, have lived here for many years, and you have become a monastery leader.

[38:56]

After I die, stay in the monastery, cooperate with the monks and laity, and protect the Buddha Dharma I have taught. If you go traveling, Always return to this monastery. If you wish, you can stay in the hermitage." Shedding tears, I wept and said in gratitude, I will not neglect anything you have said to me, both for the monastery and myself. I will never disobey your wishes." Then Dogen, shedding tears and holding his palms together, said, I am deeply satisfied.

[40:01]

For many years I have noticed that you are familiar with worldly matters and that within the Buddhadharma you have a very strong way-seeking mind, a very strong aspiration to attain Buddhahood for the welfare of the world. Everyone knows your deep intention, but you have not yet cultivated a grandmotherly heart As you grow older, I'm sure you will develop it." Restraining my tears, I thanked him. At that time, the head monk Ejo, Koun Ejo Daisho, was also present and heard this conversation.

[41:05]

I have not forgotten the admonitions that I did not have a grandmotherly heart. However, I don't know why Dogen said this. Some years earlier, when I had returned to Eheji Monastery and gone to see him, he had given me the same admonition during a private discussion. So this was the second time he told me this. On the 23rd day of the seventh month of that year, before I went to visit my hometown, Dogen told me, you should return quickly from this trip. There are many things I have to tell you. On the 28th day of the same month, July,

[42:14]

I returned to the monastery and paid my respects to him. He said, while you were gone, I thought I was going to die, but I am still here, alive. I have received several requests from the Lord at the government's office in Rokuhara, which is in Kyoto, to come to the capital for medical treatment. At this point, I have many last instructions, but I am planning to leave for Kyoto on the fifth day of the eighth month. Although you would be very well suited to accompany me on the trip, there is no one else who can attend to all the affairs of the monastery.

[43:21]

I want you to stay and take care of the administration. Sincerely, take care of the monastery affairs. This time, I am certain that my life will be over. Even if my death is slow in coming, I will stay in Kyoto this year. Do not think that the monastery belongs to others, but consider it your own. Presently, you have no position, but have served repeatedly on the senior staff. You should consult with others on all matters and not make decisions on your own. Since I am very busy now, I cannot tell you the details.

[44:23]

Perhaps there are many things that I will have to tell you later from Kyoto. If I return from Kyoto, then next time we meet, I will certainly teach you the secret procedures for Dharma transmission. However, when someone starts these procedures, small-minded people may be jealous. So you should not tell others of this. I know that you have an outstanding spirit for both mundane and super mundane worlds. However, you still lack a grandmotherly heart the third time. Dogen had wanted me to return quickly from my trip so that he could tell me these things.

[45:29]

and I am not recording further details here. Separated by a sliding door, the senior nun, Egi, heard this conversation. On the third day of the eighth month, Dogen gave me a woodblock printing for the eight prohibitory precepts. On the sixth day of the month, bidding Dogen farewell at the inn of Wakimoto, I respectfully asked, I deeply wish to accompany you on this trip, but I will return to the monastery according to your instructions. If your return is delayed, I would like to go to Kyoto to see you. Do you have your permission? Dogen said, of course you do.

[46:31]

So you don't need to ask any further about it. I'm having you stay behind only in consideration of the monastery. I want you to attentively manage the affairs of the monastery. Because you are a native of this area and because you are a disciple of the late master Akan, Many people in the province know your trustworthiness. I am asking you to stay because you are familiar with matters both inside and outside the monastery." I accepted this respectfully. It was the last time I saw Dogen, and it was his final instructions to me. Taking it to heart, I have never forgotten it. So Gikai traveled with Dogen part of the way to Kyoto to this Wakimoto place and there they parted and Dogen went to Kyoto and he went back to Eheiji and then sometime after that he wrote what you just heard

[47:59]

And then for about a year and a half, or during, after he wrote this, he finally changed in a certain way. And he said to his teacher, Ejo, so Ejo was Dogen's successor. and Gikai was not. And it is said that the reason why Dogen had waited to make Gikai his successor was because Gikai lacked this grandmotherly heart. So there he was, after Dogen died, taking care of the monastery, Ejo was the successor, and Ejo was the abbot, but Gikai was really taking care of it, as per Dogen's instructions.

[49:15]

And Ejo knew that Dogen wanted Ejo to take care of the monastery, considered him the best person to take care of the community. Gikai's thinking about, what is this grandmotherly mind? And I've heard this story for a long time, and about seven years ago, we had a special session here at Green Gulch, and the topic of the session was, the topic of the lectures in the session was about the documents for transmitting Dharma, the secret procedures for Dharma transmission that Dogen was going to teach Gikai. And during one of the talks, a visiting teacher, Tsugen Narasaki Roshi, brought up the story of Gikai again.

[50:28]

And again, it really struck me that he was such an excellent person, so talented, so enthusiastic. He worked so hard, particularly as Tenzo. He did astounding things. He made, he got things for the monks that they didn't think were possible. And yet, Dogen said, he didn't have grandmotherly heart. I wondered for years, what did he mean? So part of it, maybe, is that he lacked the kindness, the kindness of the grandmotherly heart. I'm not sure about that, but that's possible. But the other part of the grandmotherly heart is a part that's a little bit surprising. It's not just total devotion and surrender to the grandchild, which is part of it, but a sense of responsibility.

[51:48]

which is not necessarily sweet sounding. When Dogen was speaking of grandmotherly mind to this monk, he was saying to this monk to practice your daily life. in such a way that you make your daily life into the Buddha way. And the grandmotherly part is actually that you do not allow, that you're responsible to make sure that there's no false view, that the things you're doing in your daily life are a part from the inconceivable Buddhadharma. Now that might not be so obvious, it wasn't to me, but Gikai finally said to, a year and a half after Dogen died, Gikai said to Ejo,

[53:25]

This past year or so, I have been reflecting on the lectures I heard given by our former teacher. Even though I heard all of them from our former teacher, now they are different in meaning than at first. The difference concerns the assertion that the Buddha way transmitted by our teacher is the correct performance of one's present monastic tasks. Even though I heard that, the Buddha way is Buddhist ritual, and Buddhist ritual is the Buddha way. In my heart, I privately felt that Buddhism must be something apart from this.

[54:30]

In other words, privately, I was still seeking outside. Recently, however, I have changed my views. I now know that the monastic rituals and conduct are themselves the true Buddha way. Even if, apart from these, there is also an infinite Buddha way of all the Buddha ancestors, still it is the same Buddha way. I have attained true confidence in this profound principle that apart from lifting one's arm and moving one's leg within one's Buddhist conduct or Buddha conduct, there can be no other reality. One time Suzuki Roshi asked me to come to his room and he said that he wanted to tell me something.

[56:08]

And he said that sometimes the talks he gives on certain topics don't go into certain details, but he wanted to tell me these things. So he gave me a talk about the emerging of difference and unity, the Sandokai. He sat right in front of me and gave me this special instruction, but I couldn't stay awake for this special instruction. I don't remember anything he said. I think this is a pretty tough point.

[57:19]

We don't like the idea, I don't like the idea to think, oh, you know, these people walking around here in some formal ritual posture think that what they're doing is true Buddha practice, that walking around doing Buddha deportment is Buddha practice. That what they think they're doing, they think that that's Buddhism. I don't like that. One of the dangers of it is that people who aren't doing that aren't doing true Buddhist practice. But this is a little different from that. but very close.

[58:29]

So it's not usually considered to be a Buddhist ritual to say to somebody, come close to me. Anybody can say that. But Dogen's faith, Dogen's view is that he says, come close to me as Buddhism and for Buddhism. We don't even like Buddhism for the Buddha way. And also that we can also understand that the Buddhas together are transmitting the Dharma.

[60:08]

That we are here together and you are lifting your arm. You're lifting your arm together with the Buddhas. But do you feel, on one side, do you feel that adjusting your robe, are you adjusting your robe with the same feeling that a grandmother takes off her own jacket in the blizzard and puts it on her grandchild. Do you feel like you're taking care of something that you care that much for in everything you do?

[61:14]

When you pick up a cup or adjust your robe, or brush your teeth, do you have this grandmotherly spirit? This is the way Buddhas are transmitting this inconceivable Dharma. This is what they actually care about. And everything they do, like, say, come close to me, or please stay here, or please come with me, or whatever they say is an act of grandmotherly kindness. And do you think that there's something else that's important besides

[62:22]

This. And if you do, don't be mean to yourself. But remember the instruction that before Buddhas were Buddhas, they were just like us. Before Tetsugikai was a Buddha, he also thought there must be something more. There must be something more than this. There must be something apart from taking care of the monastery. And he took care of the monastery in some ways more energetically than anybody. But still, even though he did, he still thought there was something else. Now maybe some other people who didn't take care of the monastery as well as him also thought there was something else. There was quite a few like that probably, because that was that group that he came from that was in the monastery.

[63:25]

They were working in the monastery but they thought that actually there was something apart. So we probably share that. It is a worldly thing, you know, to be unhappy when we're in pain. That's quite common. And it's a worldly thing to be happy when we have pleasure. But it's not a worldly thing to have pleasure. And it's not a worldly thing to have pain. It's the being happy. for the pleasure and being upset with the pain, that's the worldly part. The spiritual part is, the Buddhism part is, that the inconceivable Dharma is not apart from this pain and not apart from this pleasure.

[64:34]

Can we make our feelings of pain, can we make those, dedicate those, devote those, donate those? Can we take care of them? Can we take care of them as taking care of the teaching of suchness? The answer might be, of course, not right now, I confess. I can't take care of this pain like, okay, I'm gonna take care of this pain. I'm gonna take responsibility for this pain to take care of it for Buddhism. I can't do it, okay? Before Buddhas were Buddhas, they were just like you.

[65:43]

So it's not that you have to put your hands together in the proper Soto Zen mudra. It's not that you have to salute in the proper Soto Zen way. It's not that you have to bow, prostrate yourself in the proper Soto Zen way. It's not that you have to eat your meals in the proper Soto Zen way. It's that whatever way you eat, and whatever way you bow, and whatever way you walk, and whatever way you talk, that whatever it is, you understand that that activity is not apart from the inconceivable Buddhadharma. and that you give yourself as fully as a grandmother does to this activity.

[67:16]

And you don't grasp this activity, actually. You don't grasp it. You give it rather than hold it. So you don't make decisions on your own, you do this together with others. The criterion by which you check to see if you're giving this rather than holding it is the self-fulfilling samadhi, that you're doing it together. So when you people arrived here on Sunday and having dinner, I took my grandson for a walk. I took my grandson for a walk.

[68:20]

No, he took me for a walk. He said, let's go to the garden together. So of course, we go. In what way do I go to the garden with him? Am I grandfatherly towards him? And am I grandfatherly towards the inconceivable Dharma? Being grandfatherly to the inconceivable Dharma, I can go with him more wholeheartedly. If I think there's a grand... If I think there's an inconceivable Dharma apart from going with him, I have just betrayed the inconceivable Dharma. But it also requires that I give myself to the inconceivable Dharma when I go with him for Buddhism to live.

[69:28]

So I go with him to the garden and he wants to see the sunflowers. And then he wants to see some other sunflowers. He remembers that they were in more than one location. So we go to the other sunflowers. And then he says he wants to hear songs about sunflowers. So I sing him a song about sunflowers. You are my sunflower, my only sunflower. You make me happy when skies are gray. You'll never know, dear, how much I love you. Please don't take my sunflower away. And then he says, poppies. So then we do the poppy song. And then the sunflower song.

[70:32]

And then he carries a baseball bat with him, most places. And he goes over to a tree and starts to get ready to hit the tree with the baseball bat. And I say, don't hit the tree. You'll hurt the tree. And he swings at it anyway. And I said, don't, you'll hurt the tree. And he says, tree is crying. And I say, yeah, tree is crying. And then he says, you hit the tree, he says to me. And I said, I'm sorry. He said, you hit the bush. And I said, I'm sorry. He said, you hit the ground. And I said, I'm sorry. And we go through the rest of the garden.

[71:40]

He's telling me all the things I'm hitting. And I don't disagree with him. I just say, I'm sorry. the 28, 29 years ago and before, I thought there was some Buddhism apart from what I was doing. And still today, there's a flicker of that. Is there an opportunity here walking with your grandson? Is there an opportunity here to notice that you think that Buddhism's apart from this monastic activity of taking a walk with your grandson?

[72:51]

Can walking with your grandson be a monastic activity? The person who is inheriting the Dharma which the Buddhas are transmitting constantly, the person who inherits the Dharma is in that process and it isn't that when they start taking care of their grandson that the transmission stops. But this person must practice while taking care of the grandson. You must not pass up on this person at this moment. You must not make an exception, just like you don't make an exception.

[73:57]

Well, I'm not going to take care of my grandchild now. Now I'll let them hit the tree. I don't care. Now I'll let them fall into the pond. I don't care. No. No exception, of course. But how about the grandmotherly mind of the Buddhas that takes care of Buddhism as much as you take care of your grandchild? and how do you take care of Buddhism. I made an agreement to give a class in Berkeley tonight.

[75:45]

I'm sorry, but I feel I should go because it might not be helpful to those people if I don't show up. I request you to allow me to go give the class. So you won't see me here for a few hours. But I'll come back to the monastery and continue being led together with you in the Buddha way. I want to learn this grandmotherly heart. I want you to learn it too, so that you can plunge into this process

[76:56]

of all the Buddhas together transmitting the inconceivable Dharma. And again, I want you to forgive yourself if you slip off this grandmotherly heart and understand that your ancestors also slipped off sometimes and that they got over it and had the great joy of, forget about getting over it, but anyway, the great joy of once in a while being present, once in a while being wholeheartedly devoted

[78:01]

to this inconceivable Dharma and this wonderful practice, which is not apart from it. Now you have it. Please take care of it.

[78:24]

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ