You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

The Importance of Precepts

AI Suggested Keywords:

Dogen Zenji: In this present lifetime there are 10 million things I do not understand about the B-Dh. I have the joy of not giving rise to evil views.

The talk focuses on the importance of precepts in Zen practice, emphasizing how precepts are often overlooked yet essential for understanding and embodying true sitting meditation (zazen) as taught by Dogen Zenji. The speaker shares a personal journey of understanding the significance of precepts in aiding the fundamental intention of compassion and ethics in Zen practice. The discussion critiques the sometimes narrow focus on meditation to the exclusion of comprehensive precepts, highlighting the consequential risks of misunderstanding Zen's essence. The necessity of integrating precepts, sitting, and the Bodhisattva vow is underscored, pointing out cultural gaps in Western Zen practices and advocating for a balanced approach towards ethics and meditation.

Referenced Works:

-

Shobogenzo by Dogen Zenji: Emphasizes the transmission of Bodhisattva precepts as crucial to Zen practice.

-

Teachings of Hakuin Zenji and Ryokan: These stories inspired the speaker's personal vow to embody compassion and the ethical conduct akin to these figures.

-

Kechamiyaku (Precept Vein): Document read during Dharma transmission revealing Bodhisattva precepts as the single cause of entering the Zen gate.

-

Theravadin Teachings by Achan Chah: Highlights a traditional progression through dana (giving), shila (precepts), and bhavana (cultivation of practice), contrasting the Western approach.

-

Myojo Zenji Teachings: Stresses that only sitting encompasses true practice, yet presupposes an understanding of precepts which may not have been explicitly taught.

Related Teachings:

-

The Three Monkeys Precept: A traditional Buddhist teaching of no evil in seeing, hearing, and speaking, expanded with a fourth monkey representing the practice of not thinking to truly embody the precepts.

-

Zen Stories involving the Sixth Patriarch: Mentioned to illustrate advanced-level teachings where one avoids attachment to stages in meditation.

-

Quotes from Dogen Zenji: Dogen's near-death emphasis on the singular importance of precepts in practice.

-

Teaching by Suzuki Roshi: Suggests that the precepts help understand the deeper meaning of just sitting but is often neglected or underemphasized in U.S. teaching.

These references and teachings underscore the need to realign Western Zen practices, ensuring that ethical foundations are thoroughly integrated within meditative practices to preserve the integrity and truth of the Zen path as initially intended.

AI Suggested Title: Precepts: The Heart of Zen

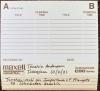

Side: A

Speaker: Tenshin Roshi

Location: Tassajara

Possible Title: Importance of Precepts to Tokubetsu Sesshin

Additional text: Original

Side: B

Speaker: Tenshin Roshi

Additional text: Side 2

@AI-Vision_v003

Clear but quiet. I think back then it was a microphone on the table so there was a distance between Reb and the microphone.

Tokubetsu Sesshin

Just the day before, Narasaki Roshi gave his talk. He spoke a little bit about personal limitations that he had, and his concern that perhaps he wouldn't be able to speak well of the Buddhist teachings. So I also have even more so considerable concern that I won't be able to handle something that I feel so deeply of the Buddhist teachings. And yet I also feel that it's very important that I bring up my concerns on this occasion where not only do we have some sincere practice-draining people here, but people from all over the world.

[01:03]

I'm going to try to bring up some things I feel very deeply about, and some things that really concern me concerning the Buddhist teaching and practice. Shortly before Dogen Zenji died, while he was with his close disciple, Tetsun Hikai, he was talking to him about the method for transmitting the Bodhisattva precepts. And he said to Hikai, please come closer. And Hikai came over to the edge of his bed and stood by his right side,

[02:16]

and listened. And Dogen Zenji said, in this present lifetime, there are ten million things that I do not understand concerning the Buddhadharma of the Tathagata. However, concerning the Buddhadharma, I have the joy of not giving rise to evil views. Depending on the correct Dharma, I certainly have correct faith. It is only this fundamental intention that I have taught, nothing else.

[03:23]

You should understand this. What I want to talk about today is my personal journey, my personal search for this fundamental intention which the Buddhists teach. At first, when I thought about speaking to you about this, I was going to try to convey it as a cultural and historical phenomenon which I've observed in America. Because what I see happening to me, I see happening to many other students of Zen. But I thought, I'm not qualified as an anthropologist, and historian of religion,

[04:36]

or even Zen teacher, to comment on the history of Zen Buddhism in America. And I know very little about it in Europe. So rather than tell you the currents and tendencies I see of Zen practice in America, I'll talk about what's happened to me. And if it applies to the rest of the nation, good. I don't know quite where to start, but I might start when I was about eight years old, sitting in my room by myself, looking out the window. And I heard a ringing in my ears, and I didn't know what it was. And I thought, perhaps this is my conscience.

[05:38]

I think something's bothering me. A couple of years later, I decided that I would do whatever gave me the most gain in my social world. And for a 12-year-old, what gave you the most gain was to be as wild and outrageous as possible. So I tried, and I got lots of attention from my other friends for being a wild boy.

[06:59]

Whenever I did anything naughty, they always got excited and praised me. They looked up to me for being the leader at causing trouble. I was successful at getting lots of social improvement and graces. I was a hero in my school for causing trouble. And I met a man, a big man, a strong man, and he noticed what I was doing, and he loved me. And he told me that when he was young, he was just

[08:06]

like me. And he looked at me, and he said, you know, it's actually quite easy to be bad. What's really difficult is to be good. And when he said that, I thought, he knows. And I decided, at that time, I'm going to try to be good. However, I forgot shortly after my decision. And then again, about a year later, I was able to realize, somehow, that I had lots of problems, that I was suffering, that I was anxious about lots

[09:18]

of unimportant things, like how I looked, and whether people liked me or not, how popular I was at school. And again, I realized that if I could just somehow be kind to everyone, I could see that all my problems would drop away. And again, I decided, as sincerely as I could at 13, to try to be kind to everyone. However, this decision was made in the quiet of my own room at home, and as soon as I got to school, I always forgot. I continued to forget for a number of years more.

[10:26]

And somewhere along the line, I read some books about Zen monks. I read some stories about Zen monks. I heard about the way they conducted their lives. I read about Hakuin Zenji and about Ryokan. When I read their stories, I remembered my childhood vow. And when I heard about these men, I said, this is the way I want to be. This is the way that all my problems and troubles with people will go away. I wanted to be like these Zen monks, but I had no idea how to become like them. But I kept reading, and gradually I found out that all these people who behaved in a way that was in a line was

[11:50]

close to my deep intention in life. All these people shared in a certain practice, and I thought, perhaps they're not so good just by chance. Perhaps they're not successful in being kind just by luck. Maybe they all do some kind of exercise that promotes this kind of compassion. And so I found out that what they all did was sit. So I started to sit. And the more I sat and the more I studied, the more wonderful I found out this sitting is. And the more I heard teachings about this sitting, the more grateful I felt to have found this sitting. Something so simple, so all-consuming, so perfect, and so effective.

[12:57]

So I practiced sitting for a number of years, enjoying it very much. But to tell you the truth, I forgot, in a way, my original motivation in practicing sitting. My original motivation was to be a compassionate person, to be a good person. I forgot about that and just practiced sitting. And also to tell you the truth, while I was practicing sitting for those years, I didn't hear much teaching about being good and about being compassionate. I didn't hear it at the Zen center where I practiced, and I didn't hear it from people from other Zen centers either.

[14:17]

But it didn't seem to be a problem because the sitting itself seemed to be so all-inclusive and wonderful. Practicing the sitting, there was a strong emphasis on wisdom, on insight. There was a strong emphasis on the fundamental of sitting with no gaining idea, of a practice that has no signs, no stages, no gain, and fundamentally no thinking. All these instructions and indications as to the heart of sitting I found totally adorable. It never crossed my mind, really, that people didn't understand, and especially that I didn't understand, what that meant.

[15:33]

Then after practicing for about 16 years, I received what we call Shiho Dharma transmission. And in the process of Dharma transmission, I read at the bottom of the document called the precept vein, Kechamiyaku. And those of you who have lay ordination or priesthood ordination in Soto school, perhaps at the bottom you may have read where it says that it was revealed and affirmed to the teacher, Myozen, that the precept vein of the Bodhisattva is the single cause of the Zen gate.

[16:49]

The precepts of the Bodhisattva are the single, one, unique cause and condition of the Zen gate. I felt somewhat surprised to see that. This had not been emphasized for those 16 years of practice. And I came to understand from that point that the gate to this signless, stageless, objectless, gainless, beautiful practice of just sitting, the gate to it was these Bodhisattva precepts. And I thought, why hadn't I heard this before?

[18:01]

And then I heard actually also that in some koan systems, at the end of the koan system, at the end of the koan training, the last thing that's taught are the precepts. And again I thought, how strange, how paradoxical that the gate is taught last, that the fundamental is taught at the end, or at the end of the training anyway. This was about 8 years ago for me, this happened. And from that time on I have been little by little putting more of my study into the precepts. And more and more I'm realizing and finding teachings in the Zen school and teachings of Dogen Zenji where he's saying that these precepts are essential and fundamental.

[19:33]

Also, just before he died he said to Gikai, in our teaching the transmission of the precepts is the most important condition. And I feel that this kind of discrepancy between the presentation of the Buddhadharma in America, or to me anyway, and the way that Dogen Zenji intended it, is partly that in Asia perhaps everyone understands this fundamental knowledge. The nature of the precepts. And they do receive it first, before they enter the Zen gate. But here in America, for me, it didn't happen that way.

[20:35]

And then I started, I heard that in other Buddhist traditions, for example the Theravadin tradition, there was a similar pattern. The Theravadin teacher Achan Chah said that the Buddhadharma is dana, giving, shila, precepts, and bhavana, the cultivation of practice. But the Westerners, when they come to practice, they aren't interested in dana and shila, they just want to do the bhavana. And I think that the birth of Zen, or the real heavy growth period of Zen in America, as my life somewhat shows, many of us started sitting right away, and we were primarily interested in the essential practice of the Zen school, the sitting.

[21:52]

But we were not so explicitly or consciously exposed to the teachings, for example, of giving and ethics, the first two paramitas. As a result of not being exposed to these fundamental practices, I feel that our understanding, or my understanding, of the fundamental intention of sitting, perhaps, what can I say, anyway, perhaps was lost. It was not so correct. And I feel there's a lot of statements in Zen which assume that the person knows that the precept vein is fundamental.

[22:54]

And therefore, when Zen teachers say, like yesterday, Narasaki Roshi quoted Myojo Zenji, who said, We don't need to recite scriptures, offer incense, practice repentance, and so on. Only sitting is required. And Dogen Zenji said, too, in the true Dharma, zazen is the straight way to correct transmission. Zazen is all the Buddha taught. Zazen includes precept practice.

[23:56]

But he said, by the way, in the true Dharma, in what we call the real teaching, but there's also a provisional teaching. So one of the characteristics, I feel, and beauty of Zen, especially as taught by Dogen Zenji, is that it is so strictly the pure, true teaching. But there is a provisional teaching also, and if people have never been exposed to the provisional teaching, there is a possibility of misunderstanding the true teaching. So that some Zen students actually think precepts are not important. Some Zen scholars say so, say precepts are the weak sister of the Buddhist practices, that really Buddhist practices are meditation and insight, and precepts are not so important.

[25:13]

Why do they feel that? Partly because when they look at the published teachings, they don't see much on precepts. A few years ago, a Tibetan teacher came to teach at the Zen Center, and he asked me some questions. He said, in your meditation, what is the object, what object do you meditate on? And I said, I felt a little embarrassed in a way, I said, well, we don't have any objects. We practice objectless meditation. And he said, oh. He said, we have that objectless meditation too in Vajrayana, but it is the most advanced meditation.

[26:14]

Usually practitioners work for many years before they can do objectless meditation. And he also asked me, what stages are there in your training? I said, well, in a way, we are mostly concerned with not falling into stages. Part of our tradition. I told him the story of where Sagan Gyoshi came to see the Sixth Patriarch and asked, how can I avoid falling into steps and stages? And the Ancestor said, well, what have you been practicing? And Sagan said, I haven't even been practicing the Noble Truths. The beginning practice. I haven't even started the beginning practice. And the Ancestor said, well, what stage have you fallen into? And Sagan said, well, how could I have fallen into any stages? Again, when I read that story, I think, how subtle, how pure is Zen.

[27:20]

But, again, the Tibetan teacher said, wow, that's very advanced. To be working on not even slipping into or clinging to the various stages of meditation. And then he also said, you know, I've talked to some of your students and there are certain things about Mahayana Buddhism which they don't seem to know about. And while this teacher was at the Zen Center, many people came up to me and said, why don't we do that, and why don't we do that? And in fact, the things that they were asking about are things we do do, but they didn't even notice it. For example, they said, why don't we make offerings, and why don't we pay homage? Why don't we make offerings to Buddhas and Bodhisattvas? Why don't we pay homage to Buddhas and Bodhisattvas? I said, we do, every time we have a meal.

[28:26]

And then they said, oh. So, these things that many of our practitioners don't seem to know we're doing, in fact, are part of our tradition. But in fact, people often don't even know it. So they don't know it. Again, that's fine, in a way. So subtle that they don't even know it. But still, I wondered, and I was concerned. So I thought, perhaps, it would be good to tell people that we actually are Bodhisattvas, that we do make Bodhisattva vows, that we do pay homage to the Buddhas and the Bodhisattvas, that we do make offerings, that we do take refuge in Buddha, Dharma, Sangha. This is not something that other Buddhists do who don't know the subtle teachings of Zen. Also, for many years at Zen Center, I never really thought, before I was ordained, I never really thought that I had taken refuge in Buddha, Dharma, Sangha.

[29:29]

We didn't say it. And, so I didn't know we did that. Now I understand again, from Dogen's mouth, from Dogen's life. Again, as he was dying, what was he doing? The last practice he did was to walk around a pillar upon which was written, Buddha, Dharma, Sangha. And he said, in the beginning, in the middle, in the end, in your life, as you approach death, in death, after death, and as you approach life, always, through all birth and death, always take refuge in Buddha, Dharma, Sangha. This basic practice, this fundamental practice. Which all Buddhists do. Many Zen students never even heard about. It was said, but they didn't hear it. Because it wasn't emphasized strongly enough.

[30:30]

And I feel that this is understandable because, in some way, our sitting practice is so essential, so profound, that we, in some sense, can overlook some of these more basic practices. But then I wondered, do we really understand, and are we really practicing Zazen in a line, in accord with the fundamental intention that Dogen Zenji taught? Do we have correct faith? Is it possible that as we practice the Buddha, Dharma, some evil, some upside down, some reversed kind of thinking is coming up and arising in our mind as we practice? I don't say it is or isn't.

[31:38]

I just say, are we wondering about that? So we always say, just sit. But it's pretty hard to understand what that means. And Suzuki Roshi said, although I really didn't hear him say it, he did say, it's written down, that he said, receiving the precepts is a way to help us understand what it means to just sit. But right after he says that, we hear the beautiful Zen saying yesterday,

[32:44]

something like, a monk asked a Zen teacher, well, what about precepts, samadhi, and wisdom? And the teacher said, I have no useless furniture in my house. This, again, is such a beautiful teaching. And it means, of course, that Zazen includes the precepts, the concentration practice, and wisdom. But I think, in my case, when I heard that teaching, it de-emphasized, those kinds of teachings de-emphasized my concern for the precepts, which I think allowed me to not study the precepts as thoroughly as I might have

[33:51]

if I had heard, from the beginning, that the precepts are the most fundamental cause in our teaching of Soto Zen. I did not hear that until recently. When I hear that teaching, and then apply myself to the study of the precepts, a kind of integrity comes into my sitting, I believe, I trust, which will help it be just sitting in its true sense. Without the precepts, I don't think I can understand what it means to just sit. When the Zen teacher says about precepts, concentration, and wisdom, that we don't have any unnecessary furniture in our house, I think he means that the precepts are not anything extra in our life.

[35:00]

That there are no precepts outside of our practice. I think that's what it means when they say that. That if you have Zen practice, there's no extra furniture called precepts, concentration, and wisdom. But what has not been emphasized, and what I'm trying to emphasize now, is that although there are no precepts outside Zen, there is also no Zen outside the precepts. This is the side which I feel would really be helpful, and which I find to be helpful at Zen Center right now. Similarly, there are no bodhisattva vows. There is no wish to save all beings outside Zazen.

[36:07]

But also, there is no Zazen outside the wish to save all beings. And again, when I read some years ago, that Ruijin Tendon Yojo suggested that before you sit, that every time before he sat, he would think, I now sit in order to save all beings. Again, I didn't know he thought that before he practiced. This was not told to me. We were not told to think that beforehand. And I think it maybe was a skillful device of the early phases of the transmission of Zen, not to tell students this kind of thing. Perhaps it was really useful. But now I feel that we're mature enough to realize that not only is there no bodhisattva vow outside Zen, but there is no Zen outside bodhisattva vow.

[37:10]

There is no compassion in addition to just sitting. But there's no just sitting in addition to compassion. Yesterday also Nagasaki Roshi talked about monkeys, talked about three monkeys. And I don't know the origin of these three monkeys. Apparently the three monkey teaching has been in Japan for a while.

[38:12]

How long has it been in Japan? Do you know? Is it fairly old? It's also fairly old in the West, isn't it? Anyway, it seems to be both in Japan and in America, we have the teaching of the three monkeys, which is speak no evil, see no evil, and hear no evil. Right? You know that one? And yesterday the way Fushida Sensei translated was, actually, first of all, no seeing, no hearing, and no speaking. Right? But we say no seeing evil, no hearing evil, and no speaking evil, which partly means no seeing other people's faults,

[39:16]

no speaking of other people's faults, and no listening to people who are talking about other people's faults. This is another meaning of this. This is a Buddhist precept, right? It's a regular Buddhist precept. And on a deeper level, it's just sitting itself, just straight, no hearing, no seeing, and no speaking. And in Nagasaki Rosho also said, nowadays everybody is quite enthusiastic about hearing about other people's faults, and speaking about other people's faults, and finding, seeing if you can find out what's wrong with people.

[40:18]

Of course, many people make a good living trying to find out what's wrong with the way people cook, with the way people write, with the way people make art, with the way people make movies. Can you find out what's wrong with it? And tell everybody. And everybody else can tell everybody. This is our way now, right? Intense looking for, hearing about, and speaking about the faults of other people's work and life. But then he also said that we need a fourth monkey on top of these three. A fourth monkey of not thinking. In other words, if we practice not seeing, not speaking, and not hearing evil with some fixed idea, a fixed idea of what that means, this still can cause problems.

[41:23]

That in order to understand the precepts, we must practice not thinking. If we sit on top of these three practices and think about them, and understand them by our thinking, we will have a tendency to say, this is right, this is wrong, this is ethical, I am ethical, I am helping people. So, the actual precepts must be practiced in conjunction with just sitting, or not thinking, or no thinking. In order that they be received and lived, but not held to in a limited, fixed way. Thinking that, I know what these mean,

[42:24]

I'm practicing, this is, this is ethics. The problem, the tricky part for Zen students is in practicing no thinking, sometimes they also practice, forget about the precepts. Since no thinking is what protects you from apprehending transgression of the precepts, or non-transgression of the precepts. We sometimes just forget about the precepts. So while practicing, not speaking, not hearing, and not seeing others' faults, while doing those practices, we also do not apprehend any fixed nature to these practices. So, receiving the precepts, we must practice just sitting, we must practice no thinking.

[43:26]

If we don't practice no thinking, the true meaning of these precepts will not be transmitted to us. But if we don't receive these precepts, the true meaning of no thinking As a kind of antidote to, I would say, the lack of awareness of ethics in our practice, I would say that we have been too much on the non-dual side of ethics. And in a way, we have to also bring in the more conventional, tentative, provisional teaching of ethics to go with this wonderful, pure, true teaching of ethics to balance. I feel that the country is asking the Zen school

[44:29]

to do this. I would even say they're kind of pounding on our door saying, what are you people doing about the precepts? What is your stand on ethics? Or what is your no-stand on ethics? What is the true understanding of goodness in the Zen school? What do you mean by avoiding evil thoughts arising in conjunction with the Buddha Dharma? Dogen Zenji said, however concerning the Buddha Dharma, I have the joy of not giving rise to evil views. What are the evil views that he did not give rise to in conjunction with the Buddha Dharma? He must have been concentrating wholeheartedly on the Buddha Dharma and watching carefully for these evil views

[45:30]

in order not to let them give rise and take over in his life. He must have known something about these evil views and I feel that that's his teaching to show us these sidetracks. But again, he did say on his deathbed that in our teaching the transmission of the precepts is the one important condition, the most important condition for our practice of just seeing. If we all are completely to the bottom of our heart committed to practicing good and avoiding evil ways and living for the benefit of all beings, then I think

[46:32]

if we receive those precepts we can safely enter into this wonderful practice of sitting which has no stages, no signs, no gaining, which is so subtle, so pure, so ineffable that no one can say anything about it. Without receiving these precepts if we enter into Zen practice it is possible that we will become lost in the wonderful ineffable ocean of inconceivable practice. I feel in my own life that's happened to me and it looks to me like with some other people they've also realized this. So,

[47:34]

I don't want to say that I've been able to follow these precepts or understand these precepts. I'm only saying that I realize more and more how important they are for our wonderful practice of sitting. Do you have any comments? Wonderful. In my talk I have the message that I'm going to speak harder than what you're asking for. I'm going to

[48:42]

speak what you're asking for. I'm to harder than you're for. going to than And what I've noticed is that we tend to be in a position where we depend on one system. And because of our cultural distracting on individual intent and personal expectations, social activity, where everything is up to personal expectations, the literature that I've seen on the precepts has become very vague as to just what they mean. And I find myself struggling with that. My focus is not human sexuality.

[49:49]

That's a very open and personal position. And I'm interested in hearing more about how personality is clearly describing having a clear understanding of sexuality and self-identity. Well, in regard to that precept of not misusing sexuality, no one can say for you, but in your own life, you can look to see. Look at the other precepts. Study the other precepts to help you understand that one. In the realm of sexuality, are you practicing good? Are you living for the benefit of others? Are you avoiding any selfishness or evil in relationship to that? In the realm of sexuality, are you taking refuge in Buddha to the bottom of your heart?

[50:52]

Are you taking refuge in the teachings of Buddha? Are you taking refuge in the community of practitioners? Do you practice those things in that realm of sexuality? Look at those things. They may bring some light to that behavior. In the realm of sexuality, do you take anything that's not given? Are you at all deceitful? Is there any intoxication involved? And so on. Look at all the other precepts to guide you to the correct understanding of the one on sexuality. Personal interpretation is unavoidable. Therefore, in order to understand, use the precepts to understand the precepts. And also use your sitting practice to understand the precepts. Use the Sangha. Take refuge in the Sangha means you ask your friends, What about this precept? I'm thinking of this or that. What do you think of this?

[51:55]

Talk to your teacher about it. Look in the scriptures about it. Use the other 15, 40,000 precepts to help you understand each one. In other words, study the precepts. Wholeheartedly study them, moment by moment, as a way to understand them. And again, if I say, I now have understood the precepts, this is called breaking the precepts. It's not the perfection of ethics to say, I am moral, I am ethical, I follow the precepts. That's not. Perfection of ethics is based on, I want to study the precepts, I want to practice the precepts forever. I want to perfect the precepts. It's not to say, I have perfected the precepts, or I haven't perfected the precepts. Perfection of ethics is not to get into the non-transgression or transgression.

[52:56]

But always study the precepts, with your friends and teachers, with the Buddha's teachings. And never stop and say, now I know what's right. Just, I want to know what's right, and study it. Thank you. I thought it was a very good design for me. I was thinking, you told the story about being able to hear the rain in your ears. And maybe, as you put it, maybe, maybe I've done something wrong. One really good guide for me is, if I see something that I don't want anybody else to know about, then it's a red flag for me. Oh, why wouldn't I want anybody to know about that?

[54:00]

It's helpful to, to try and understand the precepts. Would I want my teacher to know about it, or would I want somebody from my precepts to know about it? I think, Dogi, then you said something like, you should behave in such a way that even in the dark, when nobody else is seeing, you practice good. Thank you, Christophe. I'm very much moved. First, firstly, thank you.

[55:03]

Even later on, after I interpreted it, I thought I should have interpreted it. Not useless furniture, but unnecessary furniture. I think that just fits to what you said, what's said now. Who said that? Let them hear what you said there. No, I was just changing my translation. I thought later on yesterday, this is a good chance to correct my... No, you shouldn't say that. Yes, you shouldn't say that, because your translation did a very good job. Thank you. I missed a lot, usually, Yugen Roshi chops up for my translation, so it's very easy, but yesterday was long, so I sometimes forgot to translate. But anyway, second part,

[56:05]

I think your talk is very important, not only for the future of Zen and Buddhist, for the future of this country, but all worldwide. Zen stresses on freedom, but if it goes along with individualistic ways, then it won't last. And that stress on bodhisattva vow, bodhisattva vow, is very, very important. If we don't think of it always, if we forget it, maybe just opposite way of this course, which is to promote Zen and Buddhism, but we practitioners, especially those highly regarded,

[57:09]

become pretentious, going very freely, and then Zen and Buddhism, in the long run, will die. Super point of Buddhism is essential, not self, and bodhisattva vow, to go with all beings, not only human beings, but all beings, water and wind, most super teachings, you can realize. And I think that this is a very good, timely warning. Thank you. Thank you.

[58:15]

Would you like to... Yes. I would like to say that from the bottom of my heart, I was very glad to hear you talk. My practice has been one foot in one country, and one foot in the other. And while practicing in one country, I have been very deeply concerned about the practice in my own country. When you say that we don't need vows and altruism, that is said from a context of a country that has had Buddhism for 15 centuries, 15 centuries of celebration,

[59:16]

of ceremony, of ritual, of beautiful anticipation of that great community. And although there was something of meditation which entered Japan in the beginning, in the 600s and 700s, it did not really continue until the time of Visayas and Dogas in the 1200s. 600 years later, we have to have that kind of a base of celebration and incense offering that teachers could then say, put it aside and be with true, proudness still. And we have methods in the United States of true, grounded stillness, but not from whence it comes. A teacher like Thich Nhat Hanh is considered the epitome of peace

[60:20]

because he has lived long peace. And for us to understand true, grounded stillness, we must first of all know how the connection, how we can have stability with the importance of the precepts and very much more of the tradition of Buddhism. Then can our young students truly achieve that. Thank you for the invitation. I hope this talk will be a chance to bring us up to date. Narasaki Yoshi wants to be interviewed because he couldn't understand English. And I said, maybe I ask the lecturer to give us time for us to make noises But at that time,

[61:21]

it may be more impolite, he said. So, he wanted to help. So, my talk is to a great extent inspired by what Narasaki Yoshi said yesterday. And I know Narasaki Yoshi and his brother are very clear and totally committed to the precepts. That's why I'm really so inspired by what he said because he has that grounding. Thank you for it.

[62:00]

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ